Jeffrey Epstein is under indictment for sex crimes in Palm Beach, Florida, and I’d expected that when he came into the office of PR guru Howard Rubenstein, he would be sober and reserved. Quite the opposite. He was sparkling and ingenuous, apologizing for the half-hour lateness with a charming line—“I never realized how many one-way streets and no-right-turns there are in midtown. I finally got out and walked”—and as we went down the corridor to Rubenstein’s office, he asked, “Have you managed to talk to many of my friends?” Epstein had been supplying me the phone numbers of important scientists and financiers and media figures. “Do you understand what an extraordinary group of people they are, what they have accomplished in their fields?”

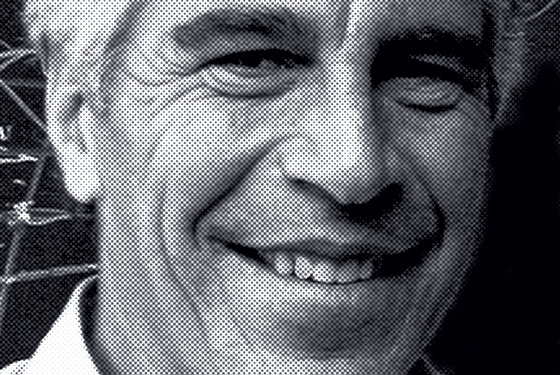

One of the accusers—a girl of 14—had put his age at 45, not in his fifties, and you could see why. His walk was youthful, and his face was ruddy with health. He had none of the round-shouldered, burdened qualities of middle age. There was nothing in his hands, not a paper, a book, or a phone. Epstein had on his signature outfit: new blue jeans and a powder-blue sweater. “I’ve only ever seen him in jeans,” his friend the publicist Peggy Siegal had reported, saying there was a hint of arrogance in that, Epstein’s signal that he doesn’t have to wear a uniform like the rest of us.

I told Epstein and Rubenstein the sort of story New York wanted to do, and Epstein seemed to find ironic delight in every word. “A secretive genius,” I’d said. “Not secretive, private,” he corrected in his warm Brooklyn accent. “And if I was a genius I wouldn’t be sitting here.” “A guy with sex issues.” A smile formed on Epstein’s bow-shaped lips. “What do you mean by sex issues?” Well … He was 54, had never married—I didn’t finish. “Are you channeling my mother?”

When I said we were interested in the agony of his ordeal, Rubenstein wrote out the word agony in capital letters on his pad. But agony seemed the last thing on Epstein’s soul. “It’s the Icarus story, someone who flies too close to the sun,” I said. “Did Icarus like massages?” Epstein asked.

Two years before, he had tried to explain himself to the Palm Beach police in the same way. After they came into his mansion with a search warrant and carted off massage tables and photos of naked girls and soaps shaped like genitalia, Epstein conveyed an urgent message to the detectives through his attorney. “Mr. Epstein is very passionate about massages … The massages are therapeutic and spiritually sound for him; that is why he has had many massages.” Epstein had even given $100,000 to Ballet Florida’s massage fund, so that the dancers might also be treated.

I never got to interview Epstein at length. His dream team of lawyers led by Gerald Lefcourt was negotiating a plea with Florida state prosecutors in advance of a January 7 trial date. It is expected that Epstein will plead guilty to soliciting prostitution and get an eighteen-month sentence—not that there’s likely to be a shameful admission. He has always had the confidence that comes with the power to dazzle and, though accused of “doing everything in Sodom and Gomorrah,” as one friend put it, seemed to believe that he could convince any halfway sophisticated person that he wasn’t the least bit tawdry.

“He lives in a different environment,” says Siegal. “He’s of this world. But he creates this different environment. He lives like a pasha. The most magnificent townhouse I’ve ever been in, and I’ve been in everything. I’ve seen a model of the house in Santa Fe … a stone fortress. A model of the house in the Caribbean—it is not to be believed. I’ve seen photographs of the apartment in Paris … How did he get himself into that pickle? That’s the mystery of Jeffrey Epstein. He’s very mysterious. Not that many people get close to him. Not that many people know him.”

The descriptions of Epstein’s character veer between visionary and big talker. His world seems to be at an astral distance from normal humanity. He lives in what is described as the largest private residence in Manhattan, about 50,000 square feet in nine stories between Fifth and Madison on 71st. Visitors report a stuffed poodle is on the piano. The house, said one visitor, is like what Hollywood might imagine when it tries to show the superrich. When Epstein noticed the visitor’s astonishment at his surroundings, he leaned against a wall with a soft smile and tapped the paneling. “It’s all fake,” he said. Epstein grew up in Coney Island, the son of a Parks Department employee. He never got a college degree. He studied science at Cooper Union and then NYU before migrating inevitably toward wealth. For two years, he was a charismatic teacher of physics and math at the Dalton School on the Upper East Side, till Ace Greenberg, a friend of the father of one of Epstein’s students, offered him a job at Bear Stearns. In one of the charmingly inevitable accidents of Epstein’s rise, Greenberg was a senior partner of the house; Bear Stearns CEO Jimmy Cayne later told New York that Epstein’s forte was dealing with wealthier clients, helping them with their overall portfolios. Leslie Wexner, founder of Limited Brands, reportedly made Epstein his financial adviser and was instrumental in building his fortune. Epstein was no footman; he loved luxury and, in his own words, saw himself as a financial architect, someone who could show the rich how to live with their money. “I want people to understand the power, the responsibility, and the burden of their money,” he once wrote. At times, his powers seemed magical. “I think it’s all done with mirrors,” says Michael Stroll, a Chicago businessman who sued Epstein (and lost) when an oil deal didn’t work out.

Stroll says he could never get a straight line from Epstein. “Everybody who’s his friend thinks he’s so darn brilliant because he’s so darn wealthy. I never saw any brilliance, I never saw him work. Anybody I know that is that wealthy works 26 hours a day. This guy plays 26 hours a day.”

Those who believe in Epstein say that his intelligence works in a lofty and synthetic manner. “His mind goes through a cross section of descriptions,” says Joe Pagano, a financier. “He can go from mathematics to psychology to biology. He takes the smallest amount of information and gets the correct answer in the shortest period of time. That’s my definition of IQ.”

A Columbia University geneticist says Epstein has that insight in science, too. “He has the ability to make connections that other minds can’t make,” says Richard Axel, a Nobel Prize winner. “He is extremely smart and probing. He can very quickly acquire information to think about a problem and also to identify biological problems without having all the data that a scientist would have … He also has an extremely short attention span. Why?—it’s not that he’s bored. He has enough information after fifteen minutes so that you can see his mind thrashing about, as if in a labyrinth. And even to doubt an expert’s statements.”

Epstein has been a munificent supporter of cutting-edge research. Axel met Epstein during the early biotech days of the eighties. Vanity Fair columnist Michael Wolff met him in the Internet bubble, in the late nineties, when Epstein invited him and a group of scientists and media types to fly to a conference on the West Coast in his beautiful 727.

“It was all a little giddy,” Wolff says. “There’s a little food out, lovely hors d’oeuvre. And then after fifteen to twenty minutes, Jeffrey arrives. This guy comes onboard: He was my age, late forties, and he had a kind of Ralph Lauren look to him, a good-looking Jewish guy in casual attire. Jeans, no socks, loafers, a button-down shirt, shirttails out. And he was followed onto the plane by—how shall I say this?—by three teenage girls not his daughters. Not adolescent girls. These are young, 18, 19, 20, who knows? They were model-like. They towered over Jeffrey. And they immediately began serving things. You didn’t know what to make of this … Who is this man with this very large airplane and these very tall girls?”

Soon after, Wolff was invited to tea at the house on East 71st Street. He understood that there was a purpose to the cultivation. Epstein was shifting his view to media, in his Über-way. “What does the media mean, where does he fit into it?” Then Epstein began to show up in the press. In 2002, he flew Bill Clinton and Kevin Spacey to Africa on his plane to discuss aids policy, and suddenly he was being written about. In 2003, he became a discreet confidant to Wolff during the period when Wolff was involved in a bid for New York Magazine. Sometime after that, Wolff saw the financial architect in his office at 457 Madison Avenue, the Villard House, where Random House once had its offices. “His literal office is where Bennett Cerf’s was. It’s an incredibly strange place. It has no corporate affect at all. It’s almost European. It’s old—old-fashioned, unrehabbed in its way.” Nearby, Wolff went on, “the trading floor is filled with guys in yarmulkes. Who they are, I have no idea. They’re like a throwback, a bunch of guys from the fifties. So here is Jeffrey in this incredibly beautiful office, with pieces of art and a view of the courtyard, and he seems like the most relaxed guy in the world. You want to say ‘What’s going on here?’ and he gives you that Cheshire smile.”

Epstein likes to say he’s private, but you don’t fly Bill Clinton to Africa without wanting attention. One friend says the Africa trip was Epstein’s Icarus moment. There was tremendous risk that the natural forces of resentment would bring the too-smart, too-rich spirit back to earth. This is the friends’ theory of the Palm Beach case: an overzealous police chief battened onto a rich man because he was not living in a box like everyone else.

The dazzling arc of Epstein’s comet came to an end—without his knowing it—in March 2005. That was when a distraught woman called the police in Palm Beach and, after at first refusing to give her name, said that she believed her 14-year-old stepdaughter had been molested by a wealthy man. The stepmother had learned about the matter in a roundabout way. The girl lived during the week at an “involuntary-admitted juvenile educational facility” because of behavior problems. She had shown up at the school with $300 in her purse, and it became the talk of her classmates. One friend called the girl a “whore,” another friend put a fist through the wall in anger, the girl left school. The stepmother got a call from another student’s mother. Soon, a policewoman was talking to the girl with a therapist present. The girl cried and dug her finger into her thigh and told the story, of going to a big house on the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway, and climbing a spiral staircase to the master bedroom, where a blonde woman of 25 who wasn’t very friendly laid out sheets and lotions on a massage table and left, then Jeff came in, naked but for a towel, and sternly ordered the girl to take off her clothes. As she rubbed his chest, he touched himself, then applied a vibrator to her crotch.

The lengthy police narrative in the case doesn’t make clear how police connected gray-haired Jeff with Jeffrey Epstein, but when the girl identified his picture in an instant in a photo lineup, police threw themselves into an investigation of the modern and palatial house on El Brillo Way.

Palm Beach Island is a 3.75-square-mile spit of land famous for towering ficus privacy hedges on Mediterranean-influenced architecture that begins at over $5 million for a single-family home. But the police did their work miles across the water, in the sprawling, drab subdivisions of West Palm Beach, where, according to police reports, high-school girls had been recruited to visit Epstein’s house. The 14-year-old was used to set up her 18-year-old go-between, Haley Robson. Robson had massaged him once and thereafter refused, but had agreed to procure girls, for $200 a head. “I’m like Heidi Fleiss,” she said. The police net went wider, to malls and community colleges, and Olive Garden restaurants and trailer parks, and the story was always the same. Skinny, beautiful young girls were approached by other girls, who said they could make $200 by massaging a wealthy man, naked. Robson said Epstein had told her the younger the better—which she said meant 18 to 20. The rules were simple. Tell him you’re 18. There might be some touching; you could draw the line. “The more you do, the more you are paid.” A couple of the girls said they went all the way into the experience—one told police she visited 50 times, another hundreds of times, both having sex with Epstein and Nada Marcinkova, a then-19-year-old beauty who Epstein told one of them was his “sex slave”; he’d purchased her from her family back in Yugoslavia.

Epstein’s friends’ belief that he was targeted for his big life reflects the fact that the police locked onto Epstein’s sybaritic lifestyle. They made careful note of the girls’ thong panties, the shape and color of the sex toys Epstein favors, and the erotic art in his home, from photos to the mural of a woman to the statue of the man with a bow. Police repeatedly pulled his trash to dig out phone messages and kept an eye on his private planes. Once, they even reported on Wexner’s plane, noting the procession of Cadillac Escalades that made its way across the tarmac. After word of the investigation got back to Epstein, through his girls, police served a search warrant at the house right under the noses of New York decorator Mark Zeff and architect Douglas Schoettle, who were there planning a renovation, and seized a dozen or so photographs of naked women the girls had described as well as the penis- and vagina-shaped soaps.

Those soaps were even in guest bathrooms. No wonder; Epstein didn’t see his sex life as tawdry, wasn’t hiding it from his circle. Wolff believes that Epstein had created an idealized world from “a deep and basic cultural moment” once epitomized by Hugh Hefner. “Jeffrey is living a life that once might have been prized and admired and valued, but its moment has passed … I think the culture has outgrown it. You can’t describe it without being held to severe account. It’s not allowed. It may be allowed if you’re secretive and furtive, but Jeffrey is anything but secretive and furtive. I think it represents an achievement to Jeffrey.”

Some girls who “worked” for Epstein—the term favored by the unfriendly assistant, Sarah Kellen, who allegedly kept the Rolodex—seem to have embraced that fantasy, too. One girl said she was “so in love with Jeff Epstein and would do anything for him.” Two college girls/aspiring models were matter-of-fact about what they’d done, and surveillance reports describe a fleet of girls jogging into the house.

But generally the girls’ feelings as portrayed by police interviews ranged from disgust to fear. Epstein was the hairy troll under the bridge they had to pass over to get quick money. One girl “stated she was very uncomfortable during the incident but knew it was almost over.” Another kept looking at the clock, and Epstein said she was ruining his massage. Other girls said they were weirded out, grossed out. They didn’t like his egg-shaped penis, definitely didn’t want it inside them. Some couldn’t say just what Epstein was doing because they kept their eyes averted. Two or three girls started crying when they talked to police, one hysterically. One wanted to tell the police but knew that he was “powerful” and was afraid he would come after her family. A 17-year-old model described an uncomfortable encounter in which Epstein offered to help her get jobs, then belittled her modeling portfolio before cajoling her to model the underwear he’d bought for her. A 16-year-old who needed money for Christmas said she was so upset by Epstein’s removing her underwear as she massaged him that she broke off her friendship with the girl who brought her. Another called Epstein “a pervert.”

Epstein clearly did not see it that way. The girls knew what they were getting into and came willingly and were well paid. He was a sexy guy who was working to give the girls pleasure. The master bedroom was a sensual place, with a mural of a naked woman and a hot-pink couch, and a wooden armoire with sex toys. The lights dimmed, music came on. Still, it is a stretch to say Epstein’s love shack was like Hugh Hefner’s. Playboy was state-of-the-art pornography for the sixties. Today, cutting-edge porn is men with bankrolls picking up young amateurs, say, high-school cheerleaders or college girls on break, and daring them to go further and further for more cash, all the way to sex toys and lesbian sex. At 52, Epstein was outside the demographic of the makeout artists of The Bang Bros, Girls Gone Wild, and Coeds Need Cash, but he surely saw himself in that erotic milieu, and seems to have been shocked that his activities would result in a police investigation.

His claim that he’d given a total of $100,000 to Ballet Florida for massage was absolutely true. “The massage and therapy fund is excruciatingly important to us. It’s part of a dancer’s life to have daily massages,” says the ballet’s marketing director, Debbie Wemyss, who notes that Epstein’s generosities preceded his public troubles. Police were not impressed. They interviewed a licensed deep-tissue masseuse whom Epstein frequently employed. She said she got $100 an hour, and there were no happy endings.

The 14-year-old told Epstein she was 18 and in the twelfth grade. In Florida, this is not a defense. The law protects the young by placing the burden on the adult to learn the truth. And while Epstein’s girls might have fooled a lot of people—they were tall and grown-up—it’s difficult to believe Epstein wouldn’t have suspected some were underage. (Though Epstein later passed a lie-detector test saying that he believed the girls were 18.) Girls needed to be driven home or given rental cars. Offered whatever they wanted from Epstein’s chef, they often gobbled cereal and milk. One 16-year-old told police that Epstein told her repeatedly not to tell anyone about their encounter or bad things could happen. Alfredo Rodriguez, a houseman, told police that at his boss’s direction, he brought a pail of roses to a girl to congratulate her on her performance in a high-school drama.

“He has never been secretive about the girls,” Wolff says. “At one point, when his troubles began, he was talking to me and said, ‘What can I say, I like young girls.’ I said, ‘Maybe you should say, ‘I like young women.’ ”

Epstein mounted an aggressive counterinvestigation. Epstein’s friend Alan Dershowitz, the Harvard law professor, provided the police and the state attorney’s office with a dossier on a couple of the victims gleaned from their MySpace sites—showing alcohol and drug use and lewd comments. The police complained that private investigators were harassing the family of the 14-year-old girl before she was to appear before the grand jury in spring 2006. The police said that one girl had called another to say, “Those who help [Epstein] will be compensated and those who hurt him will be dealt with.”

By then, the case was politicized. The Palm Beach police had brought stacks of evidence across the waterway to the Palm Beach County state attorney’s office, but the state attorney apparently saw the main witnesses as weak. One had run away from home, lied about her age, and bragged about her ass on MySpace. Another had a drug arrest and had stolen from Victoria’s Secret. The police wanted numerous felony charges against Epstein as well as charges against Haley Robson and Sarah Kellen. Then they heard that the state attorney was preparing a deal with Epstein giving him five years on probation and sending him for psychiatric evaluation. The police chief, Michael Reiter, accused the state attorney of bending over backward for a rich man and then turned the matter over to the FBI.

Finally, in July 2006, the Palm Beach County state attorney’s office handed down one indictment of Epstein on a felony count of soliciting prostitution. There is no reference to minors in the indictment. Reiter was enraged. He released a letter he had sent out to five underage girls that read “I do not feel that justice has been sufficiently served.”

Epstein’s lawyer said that Reiter was out of control, but the police chief was having an effect. The U.S. Attorney’s office began an investigation, and the dream team added another member, Kenneth Starr, the former Clinton prosecutor.

One of Epstein’s friends told me, “He thinks there’s an anti-Semitic conspiracy against him in Palm Beach. He’s convinced of that. Maybe it’s a defense mechanism.” Palm Beach was historically a bastion of Gentile privilege. Vanderbilt and Glendinning and Dillman and Warburton are still engraved on the public fountains, and the Everglades Club with its espaliered trees and brass plates reading private seems stuck in the time of the Gentlemen’s Agreement. Yet the anti-Semitic charge disturbed Jews whom I asked about it in Palm Beach. Michael Resnick, rabbi at the oldest synagogue on the island, Temple Emanu-El (circa the sixties), says he strongly doubts that Epstein is a modern Dreyfus. “There’s no way, shape, or form that you can say that Palm Beach is a bastion with respect to religion. Individuals, yes. And there are some places that it is not an asset to be a Jew.” Once Palm Beach tried to keep synagogues from opening. There are now four on the little island, including an Orthodox shul started by Slim-Fast founder Danny Abraham. Josè Lambiet, gossip columnist for the Palm Beach Post, says, “Half my sources on the island are Jewish socialites.”

Lambiet says the case has fed rage within the community over Palm Beach rules: The rich never have to do time. William Kennedy Smith in 1991, Rush Limbaugh, lately Ann Coulter for a voting infraction.

Maybe it was inevitable that religion would come into the case. Peggy Siegal says Epstein’s two big charitable causes are science and Israel. His Brooklyn homies Dershowitz and Rubenstein are also major Israel supporters. Dershowitz has written a book about lingering anti-Semitism in elite life. Now throw in the fact that the Palm Beach police asked at least three of the girls whether they had noticed whether Epstein was circumcised. “I asked … if she knew what being circumcised meant,” the officer stated in regard to the 14-year-old.

Of course, that might be evidence. But other details in the police narrative seem to derive more from Edgar Allan Poe’s psychological tragedies than from Philip Roth’s sociological comedies. Epstein is licensed in Florida to carry a concealed weapon—he has a Glock—and a shower on the first floor was given over to a gun safe. One girl said his chest was so pumped up he appeared to be on steroids. He had a Harley next to the many black Mercedeses, but his Florida license was expired. Now he was licensed in the Virgin Islands and gave his “permanent residence” as the same address as Island Yachts.

Notwithstanding the room on the first floor with floor-to-ceiling books, the general aura is cold and joyless and lonely, that of a man in his fifties denying death by giving himself over completely to the sensual life, with the help of Brit, Alexis, Rhiannon, Sherry, Nicole, Haley, and Joanna.

The police narrative has overtones of a man avoiding all connection or intimacy. For years, Epstein had had a companion in a woman who could take him on if any woman could: Ghislaine Maxwell, the daughter of Robert Maxwell, the British newspaper baron, a Jew born in Czechoslovakia, who died mysteriously off his yacht in 1991. The British tabloids say that Epstein reminded Maxwell of her father and that she brought him into a Continental world. The Broadway and movie producer Jonathan Farkas says he and his wife used to double-date with the couple. Maxwell spent time at the Palm Beach house, and the police narrative says that she even hired an assistant-cum-masseuse for Epstein. But that was five years ago, and the girl was 23, at a local college. Maxwell never showed up in all the surveillance, only her stationery.

Epstein’s activities seem to have devolved in recent years. Juan Alessi, his longtime houseman, told police that toward the end of his employment, the girls were “younger and younger,” and he often had to wash off vibrators and “a long rubber penis” left in the sink. The next houseman, Alfredo Rodriguez, said that he found the sex toys he had to wash “scattered on the floor.”

No need to worry about dirty laundry, if there’s someone to do it.

The U.S. attorney’s investigation put Epstein in a bind. If the Feds brought a case and he lost, he would be imprisoned for a mandatory minimum ten-year sentence. Given the choice, it appears that Epstein will not gamble on a trial but make a deal with the state attorney on the prostitution charge.

Not that he is likely to admit that he did anything wrong. Throughout his ordeal, Epstein maintained the air that there was nothing sordid about his actions. His wealth seems to have endowed him with utter shamelessness, the emperor’s new clothes with an erection. Even Alan Greenspan has lately raised the moral questions brought on by the gap between the rich and poor: The poor will begin to feel that the social contract was not made in good faith. Epstein’s friends say that on this matter, he has a philosophical position.

“Fundamentally,” Wolff says, “it’s about math. That on a macro level it inevitably happens that the rich get richer. And then at some level the rich get richer on a geometric basis. Jeffrey’s point is that this whole issue is—it’s just mathematics at this point. This is the nature of a successful economy. The more successful the economy is, and that would be the goal of everybody, a successful economy, the greater the discrepancy actually is.”

There is no better place to observe how Epstein’s mathematics work than Palm Beach. The only signs of life are crews of Spanish-speaking laborers on teetering ladders clipping the high hedges, not far from Bulgari and Valentino and Tiffany. It is a few miles on the other side of the bridge to where the girls came from, the shabby sprawl of West Palm Beach, with trailer parks, boys crouched on motor scooters, and pickup trucks under sun tents. Haley Robson’s house is on an unpaved road by an irrigation ditch. An attractive blonde in her forties answers the door wearing pistachio Capri pants, and promptly slams it. “We have absolutely no comment about the Epstein case.”

Driving home with their $500, Haley said to the 14-year-old that if they did this every Saturday they’d be rich, and it’s understandable that a teenager in West Palm Beach might feel that way. The coldest stories in the police narrative are about money and service. Maria Alessi, the previous houseman’s wife, said she had cleaned house and shopped for Epstein for eight years and never had a direct conversation with him. He made it clear that he did “not want to encounter the Alessis during his stay in Palm Beach.” One girl said that when she had sex with Epstein she closed her eyes and thought about cash. “In my mind, I’m like, ‘Oh my God, when this is over you’re getting so much money.”

Josè Lambiet says the case went forward in Palm Beach despite the efforts of the dream team because of community rage arising from the class issues in the case—Epstein found the girls not from his own fancy neighborhood but from the struggling suburbs.

He has never shown a glimmer of understanding that a high-school girl could be damaged by a powerful 50-year-old’s demands, or that some of the girls were already emotionally damaged. For someone who could dream anything, it seems a little small.