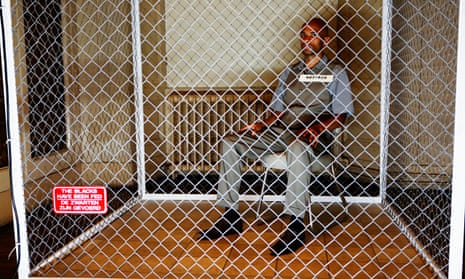

It’s the first Edinburgh rehearsal of Exhibit B and there’s mutiny in the air. The work, a highly controversial installation by the South African theatre-maker Brett Bailey, is based on the grotesque phenomenon of the human zoo, in which African tribespeople were displayed for the titillation of European and American audiences under the guise of “ethnological enlightenment”.

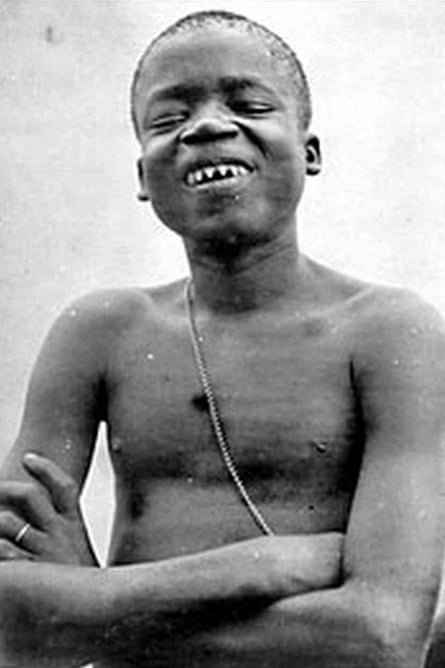

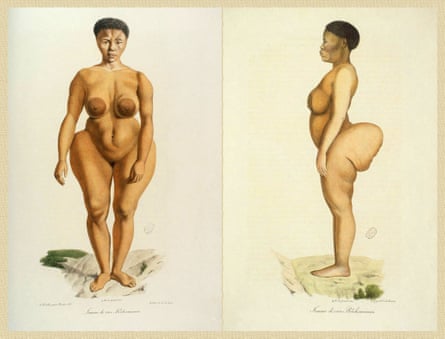

The zoos, which blossomed in the 19th century and continued right up to the first world war, sometimes took place in entirely transplanted tribal villages, but also in the freak show context of local fairs, where the infamous Hottentot Venus, as Sara Baartman was called, was poked and gawked at because of her large buttocks and “exotic” physical form. Perhaps the most extreme case was that of the Congolese pygmy Ota Benga who, in 1906, was put on display at the Bronx zoo in New York alongside the apes and giraffes. Bailey’s installation aims to subvert the premise of the zoos by replacing its exhibits with powerful living snapshots depicting racism and colonialism: a black woman chained to the bed of a French colonial officer; a Namibian Herero woman scraping brain tissue out of human skulls; the slowly revolving silhouette of Baartman.

The only problem is that the young black performers, cast locally at every stop along the tour, aren’t quite getting it. “How do you know we are not entertaining people the same way the human zoos did?” asks one. “How can you be sure that it’s not just white people curious about seeing black people?” adds another. As the temperature in the room begins to rise, the group cries out in unison: “How is this different?”

As a director who has courted controversy at almost every step of his career, Bailey is no stranger to this kind of confrontation. A white South African from an affluent background, his only early contact with his black countrymen was as servants. But after the collapse of apartheid in 1994, he trekked off alone into the rural Xhosa villages where Nelson Mandela had grown up. Living for three months among sangoma shamans, he drew on African ritual and music as the inspiration for his first works: Ipi Zombie, in 1996, based on a witchhunt that followed the death of 12 black schoolboys in a minibus crash; and iMumbo Jumbo, a year later, about the quest of an African chieftain to recover the skull of his ancestor from a Scottish trophy-hunter.

His 2001 work Big Dada, which drew comparisons between the regimes of Robert Mugabe and Idi Amin, marked a shift into darker, grainier territory; and in 2006, with the unflinching Orfeus, he bussed his audience off to a post-colonial underworld of sweatshops and human trafficking. That was when he began to shun conventional spaces. “Theatres feel to me pretty antiseptic,” he says. “Working in a deserted factory or a Nazi concentration camp, the associations are deeper and wider.”

All this has led to a reputation as “Africa’s most fearless theatre-maker”, and eventually to Exhibit B, which will fill the vast cloistered space of the Edinburgh University library, not just with searing visions of past racism, but also with contemporary tableaux that Bailey calls “found objects”. These are representations of refugees and asylum-seekers that link today’s “deportation centres, racial profiling and reduction of people to numbers” to the dehumanising ethos of the human zoos.

Already seen in various European capitals, the work has proved incendiary, particularly in Berlin, where it caused fury among leftwing anti-racism campaigners, who questioned the authority of a white director to tackle the story of black exploitation. Bailey seems to relish the entire spectrum of reaction: “I’m creating a journey that’s embracing and immersive, in which you can be delighted and disturbed, but I’d like you to be disturbed more than anything.”

Back in the rehearsal room, sporting a striped beanie hat and a very pointy, ginger-flecked beard, the director looks somewhere between a new-age wizard and a children’s TV presenter. His entrance is suitably dramatic, sweeping into the room unannounced to fix each performer in turn with a gimlet-eyed gaze. There follows a gruelling programme of psychological exercises to perfect the show’s single dramatic device: the steely stare that each performer locks on to the spectator. “It’s very difficult to get it right,” he explains. “The performers are not asked to look with any anger at all. They must work with compassion.”

All the while, Bailey is an uneasy, almost abrasive presence, making unhelpful comments about the revealing nature of the costumes and spouting the n-word provocatively in his clipped South African intonation. “He’s a badass! He gets it done,” says Cole Verhoeven, a previous performer, hinting that his spikiness may be a strategy to weed out the non-committal. “His intention is clear. And our intentions had to be clear in order to do the work with any authenticity.”

But when one of the female performers breaks down in tears due to the intensity of the process, Bailey is quick to move in with gentle reassurance. And as the mutinous insubordination and squabbling reach fever pitch, his response is firm and decisive. “What interests me about human zoos,” he tells the group, “is the way people were objectified. Once you objectify people, you can do the most terrible things to them. But what we are doing here is nothing like these shows, where black people were brought from all over Africa and displayed in villages. I’m interested in the way these zoos legitimised colonial policies. But other than that, they are just a catalyst.”

To craft each living image in the installation, Bailey conducted intensive research, sometimes taking three months or more to build a single tableau from photos, letters, biographies, official documents, paintings. One of the most harrowing, titled A Place in the Sun, was extrapolated from an account he came across of a French colonial officer who kept black women chained to his bed, exchanging food for sexual services. “It’s a picture of unimaginable suffering,” says Bailey. “She is sitting there looking in the mirror and waiting to be raped. It’s the only way she can feed her family.”

Perhaps the most chilling, though, is Dutch Golden Age, which combined Bailey’s interest in still-life paintings with a court document detailing the horrific punishments meted out to escaped slaves. “Among the overflowing bowls of fruit,” says Bailey, “we have a slave forced to wear a perforated metal mask covering his face and a pin going through his tongue. It is about the silencing of marginalised black voices, the silencing of histories.”

And it was while sifting through thousands of photographs in the Namibian National Archives that Bailey found the subject that would be the climax of his work – the four singing decapitated heads of Nama tribesmen. “After the heads were cut off,” says Bailey, “they were mounted on these strange little tripods that were custom-made. Then I found these songs that referenced the genocide of the 1920s. So it became a set of four heads singing songs and lamentations.”

Bailey does not consider any of the pieces complete without the addition of the spectator – the labels on each work even mention “spectator/s” as one of their “materials”. And they have found audience interaction to be a profound element. “We were playing a festival in Poland,” says Berthe Njole, who had the part of Sara Baartman. “A bunch of guys came in. They were laughing and making comments about my boobs and my body. They didn’t realise I was a human being. They thought I was a statue. Later, they returned and each one apologised to me in turn.”

Bailey is unsure how the piece will go down in the UK, which has its own long and chequered colonial history. Cole Verhoeven certainly believes in Bailey’s right to ruffle feathers in telling these uncomfortable stories. “Exhibit B is monumental,” he says. “And Brett’s whiteness perhaps gives him a degree of distance necessary for wading around in this intensely painful material.”

But, looking back at some of his earlier work, Bailey is now the first to admit that pushing too hard and being too bold is an occupational hazard. “People have said, ‘White boy, you are messing with my culture. You have no right to tell the story of our spiritual practices or our history, because you are getting it all wrong.’ And I can’t defend those works today in the same way I could back then. For all I know, I could look back at Exhibit B in 10 years and say, ‘Oh my God, I am doing exactly what they are accusing me of.’ But that’s the risk you take. It comes with the territory.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion