This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

You’re sneezing a lot, and your eyes are watering. Maybe you have allergies, pets, or both. Perhaps you live somewhere with smog or in a region where the land is frequently and uncontrollably on fire. It’s 2024. You don’t really need to explain why you want an air purifier. But which one should you get?

You narrow your request — your problem is seasonal allergies, you think — and type best air purifier pollen into your search bar. Google obliges and you scan the results. First up is an ad for an Amazon listing with a star rating attached. Next up is another ad, this one for an article on a site called BuyersGuide.org. The page contains language about “our picks” and a team that has spent “hours doing research, combing through forums, and reading consumer reviews” but also, less visibly, a disclaimer: “Products and services that appear on Buyer’s Guide are from companies from which Buyer’s Guide receives compensation.” Result No. 2, in other words, is an ad for ads.

Onward to result No. 3: Another ad, this one for a mysterious site, HealthnWell, which, when clicked, leads you, confusingly, to an imitation of the same Google-search-results page hosted on HealthnWell’s domain. How this scam works is not your concern — back.

Next up is a Google “featured snippet” that sort of reads like a review — “isn’t just the best air purifier …” — but is in fact an excerpt of a product description from the website of an air-purifier company. After that, Google suggests a list of questions you might have asked instead of the one you submitted just seconds ago: “Do air purifiers help with pollen?” The answer, it turns out, is “yes,” so you scroll on, past a set of Reddit links full of deleted comments and an invitation to check out an old thread on a niche forum called Bogleheads, for fans of Vanguard investor John Bogle. As with many Google searches these days, the first page of results is effectively a pop-up ad that needs to be dismissed.

Finally, way down the page, you start to see some familiar names: magazines, newspapers, and online publications of all sorts. U.S. News & World Report quotes an expert and lists “reviews” but makes no claim to have tested the products directly, and doesn’t it mostly do colleges and cars anyway? “The 8 Best Air Purifiers for Allergies of 2024,” from health.com, claims to “independently evaluate all recommended products and services”; makes reference to a “Health Lab,” where products were tested; includes photos; and is written in clear, human language. Promising, but at this point, your guard is up — and rightly so. In February, HouseFresh, a product-recommendation site that specializes in air purifiers and humidifiers, published a scathing assessment of its peers and competitors. Health, HouseFresh editors wrote, mentions testing “67 air purifiers in their lab in Des Moines, Iowa, but somehow, they have published zero product reviews and they don’t make their test data available anywhere,” while the recommendations — variations of which were published across Health owner Dotdash Meredith’s dozens of properties, including People, Better Homes & Gardens, Real Simple, and the Spruce — are “plagued by high-priced and underperforming units” and “subpar devices” from notorious brands with high name recognition. (Dotdash Meredith did not respond to a request for comment.)

You scroll deeper and deeper and deeper, through a seemingly infinite list of barely distinguishable recommendations and past dozens of direct links to products you can buy, contextualized only by star ratings. Everyone suddenly seems to know an awful lot about Air Quality Index, not to mention phone batteries, credit cards, ice cream–makers, and socks. It’s a familiar feeling. Online spaces once plastered with ads — not just publications but social networks, too — are now full of salespeople working on commission. Product recommendations have eaten the web and broken Google in the process. Meanwhile, the search giant is testing a plan — recommending more products itself — that might fix things, at least for Google.

Most modern media product-recommendation sites owe at least something to the Wirecutter, now just Wirecutter, which was created by Gizmodo editor Brian Lam in 2011 and purchased by the New York Times in 2016. Its proposition was simple: It would publish straightforward tech recommendations from expert editors who knew what they were talking about, launching with short articles with titles like “The Great TV I’d Get” — a pointedly concise, authoritative counterpoint to churned out gadget coverage. It would show its work, describing research methods, asserting its writers’ authority, and, when relevant, sharing testing methodology. Gradually, it grew into an operation that more closely resembled Consumer Reports, its clear predecessor, with a sizable staff, testing facilities, and, eventually, detractors invested enough in its credibility to argue that it had, at various points, lost its way.

The Wirecutter’s most consequential feature, however, was how it made money: affiliate fees, mostly from Amazon. When available and competitively priced, recommendations from the Wirecutter would include links to the retailer and eventually others; if a reader ended up making a purchase, the Wirecutter would get a small commission. While Amazon has offered some version of this arrangement to partners since the mid-’90s, many major publishers had either ignored it, rejected the model on ethical grounds, or scraped together modest, incremental income from tagged links included in the bodies of stories that mentioned, for example, popular books. The Wirecutter, in contrast, was recommending big-ticket items directly and had started making real money. By 2016, the site reported driving more than $150 million in purchases; it was receiving commissions of a few percent and was profitable with a staff of 60.

Meanwhile, the rest of the media was confronting a future in which social platforms would not just dominate online advertising but also stop sending their audiences to — or sharing them with — publishers. Ad rates were collapsing. Sponsored content wasn’t paying off. Some publishers took this as a sign to start building, or rebuilding, their subscription businesses. Others pivoted until dizzy. Practically all of them, though, took a swing at some sort of affiliate business. All of us, I should say: New York launched the Strategist in 2016, and you can read our air-purifier recommendations here. (According to our editors, you should get the Coway AP-1512HH Mighty Air Purifier, now on sale from Amazon, which may pay us a small commission should you choose to purchase it.)

From the jump, these initiatives varied in credibility. Some simply capitalized on shifting norms around taking affiliate fees to better monetize existing review and service-journalism operations — lots of publications were and are, in some sense, fundamentally about lifestyle and stuff and had been making purchase recommendations for years. Others built commerce brands around enthusiast subject areas in which their publication already had competence or expertise. At their best, they answered questions, called out bad products, or simply indulged consumerist desire. The decline of Amazon’s own interface and search tools into a junk-filled, ad-laden mess meant that even modest category roundups and posts promoting deals had some utility.

Established publishers seeking relief from the whims of social-media platforms and a brutal advertising environment found in product recommendations steady growth and receptive audiences, especially as e-commerce became a more dominant mode of shopping. Today, these businesses are materially significant — in a 2023 survey, 41 percent of surveyed media companies said that e-commerce accounted for more than a fifth of their revenue, which few can afford to lose. It is a relatively new way in which publishers have become reacquainted — after social-media traffic disappeared and “pivots to video” completed their rotations — with queasy feelings of dependence on massive tech companies, from Facebook and Google to Amazon and, well, Google.

As commerce verticals became a standard strategy among traditional media brands, lots of other players piled into the game, too. Thousands of entrepreneurs, ranging from domain experts looking to make a few bucks to longtime internet arbitrageurs, churned out product recommendations and built baby Wirecutters, vying for the same pool of potential buyers and searchers. Social-media influencers were seeing the appeal, too, with extremely strong connections to their audiences and fewer quaint hang-ups about kickbacks, conflicts of interest, or bias. Their efforts were helped by the fact that the platforms on which they’d found their audiences were eager to get into the business of selling stuff, too.

At the same time, the big tech companies presiding over all this economic activity were adjusting the rules and protecting their own interests. Amazon reserves the right to unilaterally change its affiliate policies and rates, and it has. Meta and TikTok established guidelines around affiliate content and experimented with programs of their own. Google, which is a huge source of traffic for the affiliate economy, has found itself in a complicated but familiar position, trying to set guidelines and best practices around a lucrative category of content without giving bad actors enough information to game results, making adjustments to its search algorithms that it can describe but not share. (A spokesperson for Google responded, “Our recent Search updates are designed to surface the most helpful, high-quality content on the web, from a diverse range of sites, and we’ve launched specific improvements to show more original reviews based on expertise and first-hand experience on Search. Our shopping features are designed to connect people to a wide range of merchants and content — including reviews — that can help make a purchase decision.” The spokesperson also said that the company had not increased the number of ads over the years and that its efforts have “collectively reduced low-quality, unoriginal content in search results by 40%.”)

This, in part, is what bothered the editors at HouseFresh: Despite the existence of those narrowly targeted guidelines and policies for review and recommendation content from Google, sites publishing what the company calls “thin” posts, sometimes created with the help of AI, or by piecework contractors, still seemed to be floating to the top. They might do this on the strength of their parent brands or by playing games with SEO, making conspicuous and frequent mentions of “testing,” “experts,” and “methodology.” But it’s hard to say for sure — Google shares best practices, not rules, which it enforces privately and at its own discretion.

That there is money to be made here is now common knowledge outside the media industry: Shuttered magazines and diminished legacy brands have become appealing to private-equity firms as pure affiliate plays. A supplemental business model for publishers has, in other words, started reshaping the lower end of the content-generation industry in its image with no signs of slowing down.

These sorts of recommendations are all, on some level, a reputation game. Some publishers are building reputations around product reviews and recommendations, while others are leveraging existing reputations to recommend products their readers might be inclined to buy. Whether this amounts to capitalizing on or spending down your reputation depends in large part on execution.

A few publishers have pushed such arrangements to their logical end point. Last year, Time magazine announced a brand called Time Stamped, “a project to make perplexing choices less perplexing by supplying our readers with trusted reviews and common sense information,” with “a rigorous process for testing products, analyzing companies,” and making recommendations. In early 2024, the Associated Press announced its own recommendation site, AP Buyline, as an “initiative designed to simplify complex consumer-made decisions by providing its audience with reliable evaluations and straightforward insights,” based on “a thorough method of testing items, evaluating companies and suggesting choices.” Both sites currently recommend money-related products and services, including credit cards, debt-consolidation loans, and insurance policies, categories that can command very high commissions; the AP reportedly plans to expand to home products, beauty, and fashion this month.

Time Stamped and AP Buyline share strikingly similar designs, layouts, and sensibilities. Their content is broadly informative but timid about making strong judgments or comparisons — an AP Buyline article about “The Best Capital One Credit Cards for 2024” heartily recommends nine of them. The writer credited for the article can also be found on Time Stamped writing about Chase credit cards, banks, and rental-car insurance. On both sites, if you look for it, you’ll also find a similar disclaimer. For Time: The information presented here is created independently from the TIME editorial staff. For the AP: AP Buyline’s content is created independently of The Associated Press newsroom. By independently, both companies mean that their product-recommendation sites are operated by a company called Taboola.

If you’re aware of Taboola, it’s probably from the company’s infamous “Recommended from the Web” widgets, colloquially known as chumboxes, which have for years shown up below and around online content (ahem) with an endless supply of tantalizing and often low-quality semi-related links, some of which are sponsored. Over the years, Taboola, which is best understood as an advertising company, became a major player in affiliate marketing, too, through its acquisition of Skimlinks, a popular service for adding affiliate tags to content. In 2023, it started pitching a product called Taboola Turnkey Commerce, which claims to offer the benefits of starting a product-recommendation sub-brand minus the hassle of actually building an operation.

Setting aside the question of the quality of the recommendations, the basic arrangement is a stretch: a venerable news agency lending its brand to a chumbox firm to recommend credit cards in exchange for a slice of a sign-up commission. Or, as the AP put it, “a great opportunity to connect the consumers of AP’s nonpartisan, fact-based journalism with Taboola-powered independent product reviews and recommendations.” (The AP, which also has a team of reporters doing non-commission-based personal-finance journalism on similar topics, did not return a request for comment.)

Arrangements like this, to give Google some credit, present an irritating challenge. Here we have an organization that has been supplying hundreds of thousands of high-quality links to Google for years now getting into something … different, in a manner that might give an informed reader pause, but which isn’t fraudulent — and which is formally and practically quite similar to more and less credible and authoritative information published elsewhere by a wide range of brands.

Still, it’s largely because of Google that these arrangements are expected to work and exist in the first place, and this general type of problem isn’t remotely new — guiding and fighting with websites that are trying to succeed in or game the search marketplace has been a core challenge of running Google since it became the dominant search engine. For years, the strange economics of search have conspired to turn the simplest of questions into seemingly insurmountable problems, or at least bizarre spectacles. In 2011, it’s thousands of sites competing to write the definitive article about what time the Super Bowl starts; in 2024, it’s thousands of sites hustling to recommend the same nine air purifiers.

Last month, Google began rolling out its latest comprehensive update to its search rankings. It called out a particular problem and took the rare step of providing a deadline for compliance:

Sometimes, websites that have their own great content may also host low-quality content provided by third parties with the goal of capitalizing on the hosting site’s strong reputation. For example, a third party might publish payday loan reviews on a trusted educational website to gain ranking benefits from the site. Such content ranking highly on Search can confuse or mislead visitors who may have vastly different expectations for the content on a given website.

As of May 5, such content will be considered spam. What users will see in its place, however, is unclear. The Wirecutter, like Consumer Reports, is now part of a paid offering, meaning that in the long term, its search placement will likely suffer as nonsubscribers bounce off its paywall and Google records their clicks as failures.

But whether these changes will help, for example, HouseFresh is unclear. Before publishing its post, HouseFresh had seen its audience drop by 41 percent since September, according to managing editor Gisele Navarro. Since publishing the post, its referrals have continued to drop, and its revenues — recently in the low six figures — have plunged. (In 2023, according to internal metrics, about 139,000 purchases were made by visitors who had read HouseFresh’s recommendations, and those are just the ones the company got paid for.)

The messaging from Google, Navarro says, has been frustrating. “What they say is ‘The update is still rolling out.’ The advice from Google so far has been to wait. Wait for what?” As her site has disappeared from view on Google, Navarro has been keeping an eye on popular search terms to see what’s showing up in its place. Legacy publishers seem to be part of Google’s plan, but a recent emphasis on what the company calls “perspectives” could also be in play. Reddit content is getting high placement as it contains a lot of conversations about products from actual customers and users. As its visibility in Google has increased, though, so has the prevalence of search-adjacent Reddit spam. Since the update has started rolling out, Navarro says, she has “seen a lot of generic review sites” getting ranked with credible-sounding names, .org domains, and content ripped straight from Amazon reviews. One vexing development is the new prominence of Quora — “So much Quora,” says Navarro — the Q&A site that peaked in usefulness years ago and has massive spam and credibility problems of its own. “You can search all day and learn nothing,” she says. “It’s like trying to find information inside of Walmart.” She’s experimenting with other search engines, she says. If current trends continue, “there’s no future for us in Google Search.”

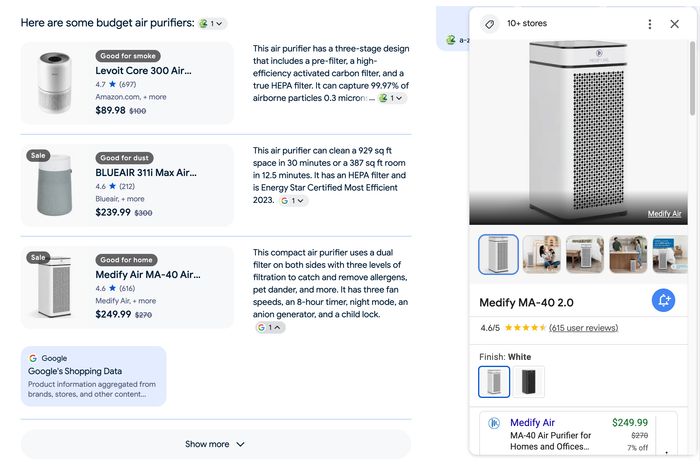

She might be right for reasons beyond hotly contested search rankings — the “ten blue links” that have been the core of Google Search for decades. Google has been testing AI-powered results with users around the world in a program called Search Generative Experience (SGE), first with users who opted in and more recently on small groups of regular users. In response to a wide range of queries, SGE will simply attempt to provide an answer rather than providing links or snippets of links. One area in which the product is taking shape — and has become quite assertive in the course of my months of testing — is product recommendations. With SGE turned on, searches about air purifiers produce results like this:

This is classic Google in that it attempts to reproduce, within its product, a category of content that was previously supplied by outside sites (now, Google will boldly tell you what time the Super Bowl starts). Its partners have identified an opportunity in its product, exploited it to an extreme, and left Google wondering, Why not us?

It’s also typical of LLM-based AI products in being plausible, fuzzily sourced and inspired, and subtly, weirdly, but significantly off. Despite a specific search request, only one of these three recommendations is a true “budget” option. SGE has inserted subcategories that I didn’t ask for and that don’t make much sense: The “good for smoke” purifier is, among the three listed, almost certainly the least good at clearing smoke; all, one assumes, are meant and good for “home.” In SGE, links are demoted from headlines to footnotes. There, we can click to reveal sources: a spammy affiliate site called A-Z Animals, which has scraped together some Amazon reviews, as well as “Google’s Shopping Data.” (According to a Google spokesperson, SGE shopping features are still “experimental” and represent one option of many for searchers. The company says its systems “take input from various sources into consideration” and “reference data from one or more sources, including web content or licensed content.”)

For now, Navarro is unimpressed with these AI experiments. “It’s just shut-up-and-buy,” she says — if you’re doing this search in the first place, you’re probably looking for a bit more information. In its emphasis on aggregation, its reliance on outside sources of authority, and its preference for positive comparison and recommendation over criticism, it also feels familiar: “Google is the affiliate site now.”