The Computers Are Coming For The Wrong Jobs

9:02 AM EDT on May 12, 2023

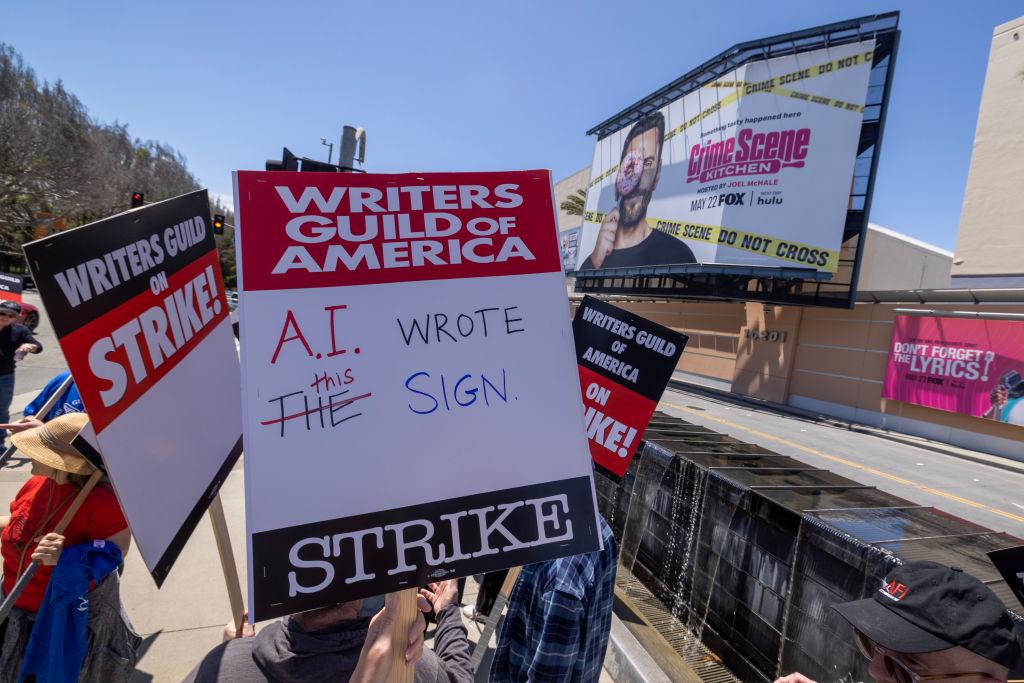

One of the funnier conceits of the ongoing Writers Guild of America strike is the producers’ insistence on keeping the door open to having AI involved in the writing process.

One reason it’s funny is that AI as it currently exists—that is, “large language model” programs like ChatGPT—only appears “free” or even “cheap” because it is being heavily subsidized by investors and tech companies that hope to eventually pass along the costs of training and operating these programs to clients like, say, large film and television studios. LLMs require millions of dollars to develop and train, and they operate on incredibly expensive, power-hungry hardware. Replacing a screenwriter with AI to “save money” is like cutting out your daily Starbucks but buying a $25,000 La Marzocco espresso machine, if the La Marzocco was also bad at making espresso, but could, with careful human assistance, produce beverages that resemble espresso.

Because that is the other funny thing about the notion of replacing writers with AI: The kind of software we are using that label on is incredibly ill-suited to the task of producing creative work. Large language models (as I learned when we did an episode on them for the podcast I co-host for The New Republic) are essentially paraphrasing machines mixed with predictive text. Because they are designed to produce strings of words based on strings of words they have been trained on, but without overtly plagiarizing, they are quite good at lying, but terrible at surprising. They are designed to produce book reports, not books.

(The third reason it’s funny is that, at least for now, material produced by machines isn’t copyrightable, meaning studios wouldn’t own anything “original” that an AI wrote for them.)

Which is not to say that the WGA shouldn’t be taking a stand on the issue. The likeliest scenario doesn’t involve AI replacing screenwriters, but rather screenwriters making substantially less money to “rewrite” AI work. But I’m not even sure the producers consider that their end goal—I fully believe they are dumb enough to think that we are a few short years away from Bing being able to independently produce a season’s worth of scripts for a procedural show about a brilliant surgeon who is also a spy and a homicide detective, much as I also believe they genuinely thought NFTs—a technology that gives people the opportunity to purchase a link to a JPEG, and also the opportunity to have that link stolen from them—were somehow the future of entertainment. We’re talking about very stupid people with too much money, a class of people so sub-literate that the new trend in creating media just for them is based around the same principles (short, declarative sentences with lots of bullet points and context clues) as the early reader books my elementary school-aged child has already outgrown. It’s no wonder that this bunch thinks having no concept of the meaning of words is not an obstacle to storytelling.

Which is not to say that there are no writing jobs that could be plausibly replaced by AI. It is well-suited at the task of blandly rewriting copy, which makes it the perfect employee of the sorts of content mills that exist to aggregate and rewrite tech or entertainment news. Of course, those sites aren’t meant to be read by humans, they are meant to get good placement in search engine results—it’s content, in other words, meant to be found by robots so that other robots can sell ads against it. AI’s primary professional role in the near term will be speaking to other AIs; the future of customer service is two AIs endlessly emailing each other back and forth, alternately demanding and refusing refunds.

But for the most part, professional writing is just not what AI is good at, and, hype aside, there’s little reason to be hopeful it’ll get much better very quickly. For some reason, when the C-suite class imagines what professions will be automated by LLM AI, they keep naming ones (teacher, therapist) that do actually require the use of language as a tool of understanding and communication, rather than a space-filler. This strikes me, again, as a failure to understand what AI is currently good at, and what various jobs actually require. A computer would do a better job owning the Oakland A’s than it would writing about them. Facebook’s expensive AI models would presumably have an easier time replacing Mark Zuckerberg than they would the African content moderators it currently pays less than $2 per hour.

Yet we keep asking computers to do some of the most complex and difficult things humans can accomplish, like driving cars or writing episodes of Blue Bloods, rather than simple tasks they are more suited for. There are jobs, after all, that require very little besides spitting out plausible-sounding answers in response to prompts; jobs in which not understanding either the prompts or your responses is not disqualifying, so long as you are broadly guided in the right direction by one or two sentient human handlers. One of those jobs is, apparently, being the senior senator from California.

If you liked this blog, please share it! Your referrals help Defector reach new readers, and those new readers always get a few free blogs before encountering our paywall.

Stay in touch

Sign up for our free newsletter