The music photographer Mick Rock, who died last week, aged 72, once said that he was “in the business of evoking the aura” of his subjects. It was his great good fortune to be working at a time when the aura emanating from the rock star likes of David Bowie, Lou Reed and Iggy Pop, all of whom he caught in now celebrated images, was both compelling and unsettling in its androgynous otherness. With Rock’s death, the truly transgressive nature of the cultural moment his photographs captured seems ever more distant.

One image of his, in particular, captures the sexual audacity of Bowie’s performances and, almost 50 years on, still carries a trace of its initial illicit charge. Shot from the side of the stage, it shows the singer simulating fellatio on Mick Ronson’s guitar during a show at Oxford town hall in 1972. Back then, the act seemed brave to the point of foolhardy in its provocation – it was only five years after homosexuality had been decriminalised in England and Wales, but that was entirely the point.

As became clear in the years that followed, Bowie’s pop-cultural antennae were highly attuned and almost preternaturally prescient. Soon after the photograph appeared in the music press, his Ziggy Stardust tour was attracting younger fans in their thousands, with glitter and eyeliner replacing the drab uniformity of utilitarian denim in both his male and female devotees. With the emergence of glam rock, which, in hindsight, seems the most extravagantly unBritish pop genre ever, Bowie’s time had come, his ascendancy propelled by what Rock later called “the titillating publicity” of that arresting image.

In the photograph, Rock’s proximity to the performers on stage is indicative of the kind of access both photographers and journalists had to rock stars in those days. Indeed, his friendship with Bowie was such that he may even have been primed to capture the moment. Intriguingly, Rock had only met Bowie a month before the Oxford gig, having travelled up to Birmingham to photograph the singer for the first time. A few days afterwards, he visited Bowie at home and they bonded in part over their mutual love for the wayward Syd Barrett, erstwhile guitarist of Pink Floyd, who had become a reclusive figure following a protracted, LSD-fuelled mental breakdown.

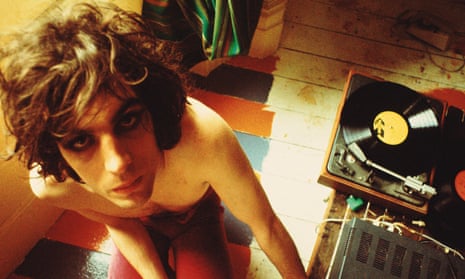

In the late 1960s, while a student at Cambridge studying modern languages, Rock had befriended and photographed Barrett not long after buying a secondhand camera on a whim from a friend. Like the pre-glam Bowie, Barrett was a hippy with a dandyish streak and, even as his sanity unravelled, had a seductively dishevelled Romantic aura about him, what Rock later described as “a beautifully burnt-out look”.

In the autumn of 1969, Rock shot Barrett reclining on the bonnet of a vintage Pontiac outside his Earl’s Court flat and lounging on the floor inside, his naked girlfriend visible in the background. One of the portaits was used on the cover of the singer’s solo album, The Madcap Laughs, Rock’s first famous picture.

When the session took place, Barrett was only 23 and Rock was just 19, both of them immersed to different degrees in the heady and dissolute hippy culture of the time. “This period produced a lot of innovation, a lot of characters who were highly creative,” Rock told the Guardian in 2015, “and I’m sure the LSD had something to do with it. I certainly wouldn’t have been a photographer if I hadn’t taken LSD. I was in the middle of an acid trip the first time I picked up a camera. It turned out there wasn’t any film in it, but it was an amazing experience, and it inspired me to start taking pictures.”

From the moment he picked up a camera on a whim, Rock was very much the right person in the right place at exactly the right time. From across the decades, the access he had to the performers he helped immortalise seems remarkable in an age when ruthlessly timed, PR-controlled interviews are the norm. His friendship with Bowie was such that he accompanied the singer backstage to meet Lou Reed at the King’s Cross Cinema in London (later to become the Scala) on 14 July 1972. He later described Reed’s performance that night as “like a Jungian journey into some primal hinterland”.

The starkly atmospheric, slightly blurry, monochrome portrait of a vacant-looking Reed that graces the singer’s Bowie-produced solo album, Transformer, was actually a live shot taken at that London show. The following night, Rock returned to the cinema to witness the only London show of Iggy and the Stooges, who were in town to record their third album, Raw Power, with Bowie in the role of executive producer. Another evocative live shot by Rock – Iggy, bare-chested and heavily made-up, leaning on the microphone stand and gazing out into the crowd – features on the cover of an album that, though all but ignored at the time of its release, would soon become a touchstone for the punk generation.

The powerful images that Rock produced in a single year resonate though the decades as emblems of a time when rock music possessed a cultural import that has long since faded. They speak of creative risk-taking, gender flamboyance and fearlessness, but also of the camaraderie of a small confederacy of outsiders and mavericks, whether performers or their image-makers.

That journey produced some truly remarkable music and portraits, the one feeding off, but also articulating, the other. “They were, by any standard, eccentric and they were threatening,” Mick Rock once said of Lou Reed and Iggy Pop. He evoked their dissonant, confrontatonal energy in images that resonate still and, in doing so, cannot help but highlight the absence of the same in present-day music.

Sean O’Hagan is an Observer writer