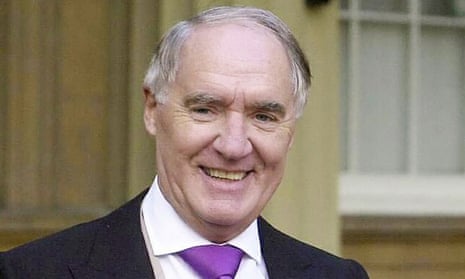

Together with his identical twin, Frederick, Sir David Barclay, who has died aged 86, was one of the Barclay brothers, the businessmen whose energetic pursuit of high-profile acquisitions, from the Ritz hotel to the Telegraph newspaper chain, was matched only by the lengths to which they went to preserve a low personal profile. It was a crusade that saw them, although proprietors of a British newspaper chain, use French courts and the more amenable French legal system to seek retractions and apologies from other news organisations, inevitably generating even greater interest in their business and personal activity.

They were two of the most successful British businessmen of their time but hung on to their trophy acquisitions for too long. Their interdependent relationship and their empire crumbled unexpectedly and dramatically when they were in their mid-80s.

The twins – David was 10 minutes the younger – were born in Hammersmith, west London, part of a family of eight children of Beatrice (nee Taylor) and Frederick Barclay, who had moved from Scotland after he lost his job as a baker. In London he opened a small shop in Olympia and also worked as a travelling confectionery salesman. The family lived in a house so close to the railway that the windows shook when a train passed.

Frederick died when the twins were 12, and at 16 they found their grounding in business in the accounts department of the General Electric Company. A few years later, they set up as interior decorators, using the cash they made to get into property, establishing Hillgate estate agents in the 1960s.

Developing a formula for hotel makeovers, they worked their way up from boarding houses, renaming Hillgate as Barclay Hotels and, in 1983, acquired three large London railway hotels sold off at privatisation – the Grosvenor, in Victoria, the Charing Cross and the Great Western (now the Hilton London Paddington). Along the way, David had a first exposure to publicity when in 1955 he married Zoe Newton, a model whose fresh-faced good looks exhorted the nation from every poster site to “drinka pinta milka day”. They would have three sons, Aidan, Howard and Duncan; after they divorced in the 80s, David married Reyna Oropeza, with whom he had another son, Alistair.

The Barclays depended on borrowing, and in 1968 they found access to large sums from the Crown Agents in curious circumstances. The government body had recently branched out from its traditional role as a procurement agency for British territories to become a property investor and banker. The Barclays’ solicitors, Davies Arnold Cooper, became the Crown Agents’ property solicitors, and Barclay Hotels was one of three hotel groups introduced by the firm. All were lent substantial sums by the Crown Agents and all defaulted on their loans.

The Barclays had proposed buying a large hotel, the Londonderry House in Park Lane, suggesting that they were preparing to go public and offering the Crown Agents an option to purchase shares. Even their stockbrokers described it as “high risk”, but when the agents asked accountants to check the figures, the Barclays successfully argued that they should exclude “the calculations and figures contained in the profit forecast and the assumptions underlying it”.

The loan was made but, as the government report into the financial failures of the Crown Agents later concluded, “the profit forecast was not met. The Barclays did not go public and the option was not taken up. The Crown Agents continued to support the group with loans which reached a total of £9.5m.” The Barclays Hotels group defaulted, while the agents were rescued by the government with £175m of public funds, escaping bankruptcy by the decision of the reconstituted Crown Agents to sell on the bad debt for £3.5m.

Undeterred, in 1975 the brothers bought and refitted the Howard hotel, overlooking the Thames at Temple, and in 1983 they broke new ground by buying the Ellerman shipping and brewery conglomerate. It illustrated their ability to strike a deal with a distressed seller, which would culminate in their capture of Telegraph newspapers.

When a bidder could not be found for the group, the Barclays stepped in: they knew the heiress Lady Esther Ellerman as a neighbour in Monaco, to which they had moved for tax reasons. In a sealed bid process, their offer was accepted, although well short of the seller’s target price. The Barclays paid £47m and sold off the ships and travel company. Six years later, the pubs and breweries alone brought in five times as much.

After the purchase, the Barclays gave £500,000 to London Zoo. Their charitable foundation, founded in 1989, has since made donations of more than £15m, largely for children’s medicine, including to the Great Ormond Street and Alder Hey hospitals. Charitable activity was the reason given for their knighthoods in 2000.

Their preference for keeping things private was reinforced in 1986 when 80 MPs signed an early-day motion against their attempted takeover of the Imperial Continental Gas Association, opposing a leveraged breakup. They withdrew their bid and, pocketing £27m from selling the shares they had already acquired, returned to the largely privately financed world of shipping, acquiring Gotaas-Larsen, a liquid gas carrier, for $750m. Fluctuating oil prices gave plenty of opportunity for arbitrage (the purchase and rapid resale of assets to take advantage of differing prices), and tankers were bought and sold, until nine years later the group was sold for a paper profit of $80m.

Somewhere along the line, the Barclays, David in particular, developed an obsession about owning newspapers. Given the near-universal testimony of their editors that they seldom interfered – or even got in contact – their motives seem obscure; a fascination with political and business news, perhaps a wish to control what was said about them, an appreciation of the value locked in some newspaper conglomerates.

But it was not, it appeared, as a judge in the Telegraph takeover battle would later describe, “to enjoy the prestige and access to the intelligentsia, the literary and social elite and high government officials which comes with that control”. The brothers spent little time in London and were not seen on the social or political circuit. But their pursuit was unremitting.

In 1992, they started with a desperate choice, the failing European, Robert Maxwell’s doomed attempt at a Europe-wide paper. By the time they closed it in 1998, it had cost an estimated £70m. But by now they were the owners of the Sunday Business newspaper (later the Business magazine), another expensive failure, and of Scotland’s premier group, Scotsman newspapers, bought for £85m in 1995 from the Thomson corporation. It was sold to Johnston Press for £160m in 2006 with a much smaller circulation and shorn of its flagship Edinburgh headquarters, which was sold off for a hotel.

The Barclays were outbid by Richard Desmond for the Express group, but in 2004 secured a greater prize – the Telegraph newspaper group. They had offered to buy it from Conrad Black 17 years before. Now, as Black fell out with his board and was pursued for payments to his private companies, he changed his mind. The Barclays moved swiftly, reaching a deal to buy from Black’s Hollinger company for $326m (£260m in 2004). Just how good a deal it was rapidly became apparent when the Telegraph directors secured a blocking legal judgment and auctioned the company. The brothers still emerged successful but at a much higher price: £665m.

Patience had also been rewarded in 2002, when the Barclays, flush from the profits of breaking up the Sears group in conjunction with Philip Green, acquired the retail group Littlewoods for £750m from the Moores family, whom they had first approached 18 years before. A year later, they added Great Universal Stores’ mail order business for £590m, to dominate the industry with a market share of more than 30% as Littlewoods Shop Direct group, rebranded in 2008 as Shop Direct, while selling Littlewoods stores to Primark for £409m. After thousands of redundancies, Shop Direct became one of the UK’s largest private retailers, but by 2020 was in difficulty.

The Barclays’ appreciation of trophy assets was marked by the acquisition of the Ritz in 1995 and later the Mirabeau hotel in Monte Carlo. But their grandest enterprise began in 1993 with the purchase of Brecqhou, a small rocky island 80 metres from Sark in the Channel, where they constructed a £60m turreted castle designed by the neoclassical architect Quinlan Terry. It has formal gardens and a vineyard as well as a helicopter pad, its own flag and postage stamps. Its internal decoration with marble staircase and gilt fittings reflected the Barclays’ taste, and a butler was on hand to light their cigars promptly at 11am each day.

The brothers took a growing interest in Sark, buying up property and businesses, which brought them into conflict with its near-feudal governance. They challenged the primogeniture inheritance laws in the European court of human rights; Sark compromised. They objected to a property payment; the islanders amended it. But when in 2008 they ran a series of candidates in elections on a Democracy for Sark ticket, they were heavily defeated and immediately closed a number of their businesses on the island. Although they subsequently reopened, it looked like pique.

The Barclays would complete each other’s sentences, and it was said that the only way to tell them apart was the side on which they parted their hair. They aggregated their business knowhow with a favourite remark – “who else but us has over a century of business experience?” Anthony Cooke, who purchased the Ellerman shipping interests, said: “David was more attuned to taking a risk … Frederick was generally willing to have a look but would never bet the farm.”

Employees and rivals remarked on their good manners even in tough negotiations. Often characterised as unassuming, they were described by a rival as “very effective stealth buyers. They come from nowhere and move quickly.” Redundancies usually followed when they acquired companies but they made the expensive decision not to close the Ritz while they refurbished, arguing that they would lose the staff – the lifeblood of the hotel.

As for newspapers, Frederick told one editor, “David is the newspaper fanatic; I just sign the cheques.” Editors, though well aware of their Eurosceptic Thatcherite sympathies, said their interventions were rare. In the 1997 general election, Andrew Neil, editor-in-chief of the Scotsman newspapers, asked the editors of his three papers whom they wanted to support. They all backed Tony Blair. When Neil contacted David Barclay, his response was, “if you think so, that’s fine by us”. When the Queen toured the new Scotsman headquarters, the Barclays, after a brief introduction, took no part, preferring a quiet cup of tea in an executive’s office.

But their impact showed in the financial management of the groups, and the appointment of David’s son Aidan as an active chairman of the Telegraph group, changed the picture. Editors were regularly shifted, and there were allegations in 2015, denied by the Telegraph, that an investigation into HSBC was called off at a time when the Barclays feared the loss of the bank’s advertising.

Bill Deedes, nonagenarian former editor of the Daily Telegraph, bitterly resented what he saw as a downmarket movement of the paper, with redundancies and new executive management from the Daily Mail. Complaining he was only kept on “as a somewhat shabby mascot” to reassure readers, he wrote ironically: “This was a newspaper they were ready to pay £660m for, but it was being produced by an unsatisfactory staff.” The Barclays took large dividends out of the Telegraph but, as all newspapers struggled, it lost money and readers, and by 2020 was estimated to be worth no more than £100m.

After the purchase, the Barclays continued their financial manoeuvres, acquiring control of two-thirds of the Coroin hotel group, which owned Claridge’s, the Berkeley and the Connaught. But after five years of bitter legal battles with the Irish investor Paddy McKillen, who owned the remaining stake, they sold out to a Qatari-owned company.

They were famously tax efficient, basing most of their businesses, including the Telegraph, offshore, and were honorary ambassadors for Monaco. But in 2017 they lost a landmark case against the Inland Revenue for £1.2bn accrued interest after an alleged VAT error 40 years before.

Their aversion to publicity remained constant. After the reporter John Sweeney landed on Brecqhou, the BBC was sued successfully in a French court for breach of privacy, as well as for libel for a broadcast on BBC Radio Guernsey, and the Times had to apologise for describing the brothers as “asset strippers”.

David once said: “We are private about everything we do. It stems from our philosophy of not talking about ourselves, or claiming how clever we are, or boasting about how successful we have been. We would, anyway, claim that we have been more fortunate than many others.”

By 2012 Frederick said in a court hearing that the brothers had largely retired from business. His brother, he said, was “seriously ill with angina”. Three of David’s sons, Aidan, Howard and Alistair, were by then closely involved with the businesses, and Frederick’s daughter Amanda worked for the Ritz.

But in 2019 it all started to go very publicly wrong. There had been rumours for some time that all was not well between the brothers. One insider claimed: “They are all at war. The old boys aren’t talking.” That October the Telegraph newspapers were put up for sale. Then hostilities broke out publicly over the Ritz.

After Amanda had been removed from the board and a sale rumoured, Frederick and Amanda accused three of David’s sons of bugging their business conversations and brought a legal case for breach of confidence. Refusing a non-disclosure order, Mr Justice Warby said the case stemmed from “the falling out between elements of the families”. Substantial parts of the business enterprises were now owned by trusts whose beneficiaries included the Barclays’ children.

The feud worsened when the sale of the Ritz to a Qatari investor was announced a few days later. A statement from Frederick threatened litigation and said he had not approved the sale. Ellerman Investments responded: “Neither Sir Frederick nor Amanda Barclay have any relevant legal interest which would allow them to disrupt the sale.”

Business attention is focused on the future of two other once trophy but now poorly performing assets – Shop Direct, now renamed the Very group, hit by £150m of PPI claims and supported by loans from other parts of the empire, and Yodel, the courier spun out of ShopDirect, which had pre-tax losses of more than £600m over seven years.

David is survived by his wife, four children and nine grandchildren and by Frederick.