Gov. J.B. Pritzker may soon issue a rare veto over a measure that he says could harm some of Illinois’ most vulnerable patients. Ambulance companies, however, say the legislation is needed to prevent a growing paramedic shortage that’s already putting pressure on the health care system and which could put people in medical jeopardy.

When the sirens of an ambulance blare, there’s a chance the emergency medical technicians within are connected to a municipal fire department and are responding to a 911 call.

But the majority of ambulances on Chicago-area roads are owned and operated by private companies that have obligations beyond 911. They transport patients to different hospitals, move patients from hospitals to a nursing homes and pick up Medicaid recipients who require an ambulance to get to a medical appointment.

Paramedic Demel Fountain has worked for Elmhurst-based Superior Ambulance Service for 19 years and now serves as an operations supervisor.

He said the pandemic has been a particularly busy time.

“We were on the front lines transporting the people who had COVID, transporting from hospital to hospital, moving people to ICUs. … In the height of the pandemic, we were transporting a lot of COVID-positive patients, so risk level was high,” Fountain said.

Fountain says he got the coronavirus himself and had to be hospitalized for a couple of weeks.

He became a paramedic because he wanted to help people, he said.

But the dangers of COVID-19 piled on to what’s already a physically and mentally stressful job, and he said his co-workers are leaving the profession.

“I’ve had people leave to go work for Walmart, we’ve had people leave to go work for Amazon. We had one person actually leave to go be a manager for Chick-fil-A,” Fountain said.

Can they be blamed? President of the Illinois State Ambulance Association Christopher Vandenberg says it’s a function of what companies are able to pay.

The wages for those jobs are on par with what private ambulance companies can pay — but becoming a licensed EMT or paramedic takes time and requires training.

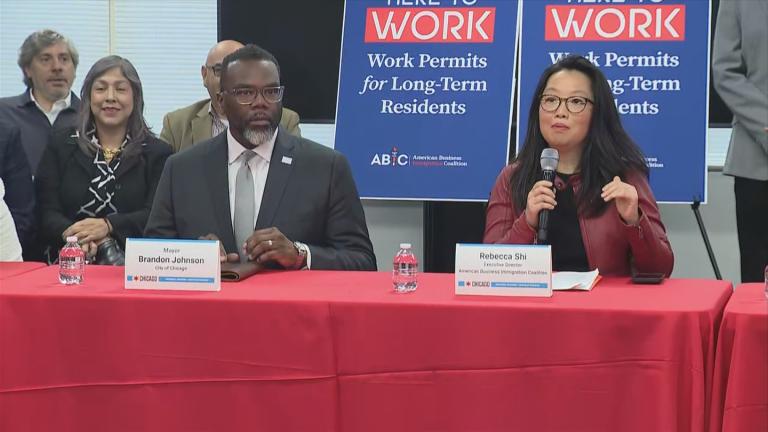

(WTTW News)

(WTTW News)

To work in an ambulance, Vandenberg says, “You have to go to school, to EMT class, and then you do a very difficult job of moving and lifting patients and it’s an extraordinary stressful job, particularly given the pandemic.” Alternately, he points out, you could “start tomorrow at McDonald’s and flip burgers or go to Starbucks and be a barista, you know?”

His companies – Vandenberg, Trace and ATI Ambulance – would like to increase staffing by at least 20%.

He said companies don’t have a lot of financial leeway to hike wages, however, because it’s a rate-regulated industry, with revenues largely coming from Illinois’ Medicaid program and the federal Medicare program.

“Both of those, they’re telling us the exact amount that we’re going to get paid,” Vandenberg said. “We can send them a bill for as large as we want, they’re going to say, ‘Thank you very much, here’s the amount that we’re paying you according to our fee schedule.’ When there are increases to our costs — wage increases for example, that are dictated by minimum wage mandates or they’re just market pressure — we don’t have the ability to pass those costs along to anyone. So we’re trying to figure out how to do that, how to pay our people.”

One method: legislation. House Bill 684 would allow private companies to no longer have to submit claims for non-emergency transport trips to managed care organizations. Instead, they would request reimbursement directly from the state’s Department of Healthcare and Family Services (HFS) under a fee-for-service model, as has been done since this spring for emergency transports.

That route would simplify the billing processes for ambulance companies so they could focus on patients, and speed up the cash flow to private ambulance companies so they’d be able to hire more paramedics, Vandenberg said.

“Ultimately, it has to do with predictability and, ultimately, ease of getting paid,” Vandenberg said. “Right now when we’re dealing with these managed care organizations they simply cannot process our claims.”

Vandenberg said the association’s five largest members were polled earlier this month, and they responded that in 2020 they provided 80,000 Medicaid managed care organization rides. As of early August, 15,000 had yet to be reimbursed.

“While the dollar amounts may be small in the world of MCOs, where they’re paid billions and billions of dollars a year, that $2.5, $3 million dollars is essential and critical to making sure that there are ambulance services that are available,” he said. “Fifteen thousand transports that haven’t been paid — that is just a staggering number of unpaid trips.”

Rep. Will Davis, a Democrat from Hazel Crest who is a co-sponsor of the legislation, said whether claims are paid appears arbitrary.

“In some cases the managed care organization says, ‘We’re simply not going to pay that claim.’ And one of the reasons that we’ve heard is that, ‘You are providing too many trips to that individual, or too many times to that household.’ So they’re just making an arbitrary decision, when again, the ambulances don’t have the luxury of not responding. They are mandated to respond when they receive those calls,” David said.

Healthcare and Family Services chief of staff Ben Winick said it’s not arbitrary at all.

The primary reason companies are having trouble getting claims for non-emergency trips paid is because the companies are not able to demonstrate that the transports were medically necessary, as is required by federal law, Winick said.

Payments also can’t be paid and processed until they’re submitted, and HFS said it just learned of one ambulance company that submitted thousands of claims to a managed care organization dating back two years.

Samantha Olds Frey, the head of the Illinois Association of Medicaid Health Plans, the state association for managed care organizations, likewise disputed Vandenberg’s numbers.

Regardless, she predicts if the ambulance companies get their way, the plan will backfire.

“When we look at denial rates — these are when claims are submitted and somebody doesn’t pay them — the health plans’ denial rate is somewhere between 10%-15%. When we look at HFS’s denial rate for these same services — non-emergency ambulances — their denial rate is 40%. So significantly higher than what the Medicaid health plans are seeing,” Frey said. “So we worry that this bill, House Bill 684, is actually going to exacerbate the challenge that the ambulance industry’s saying they’re trying to solve.”

Managed care organizations, HFS and Pritzker’s office also argue that the bill, if enacted as law, would result in harm for Medicaid recipients who need non-emergency ambulance transportation.

At a base level, HFS Director Theresa Eagleson said it will be confusing for Medicaid customers who otherwise coordinate their health care — including planning and signoff for ambulance trips — through their managed care organizations.

If non-emergency trips are separated from MCOs, customers will have to call a separate number to request an ambulance ride; but they’d call the MCO for transport via a less-aggressive option, like a medic car, potentially sending Medicaid customers into a complicated customer service spiral.

“Medicaid is the only payer that really pays for non-emergency transportation,” Eagleson said. “And the reason we do that is to make sure that our customers get access to care, regardless of whether or not they have a car or certainly if they need assistance, you know, getting to those appointment because they’re frail or in a wheelchair or something like that. The Medicaid program is here to serve over 3 million people in Illinois who need help, because of their financial situation, accessing health care, and we want to make that as easy on them as possible. And if that’s a little more work for us, and some of the providers that are involved in the program, then we absolutely think that’s worth the work.”

Eagleson also said ambulance companies may put Medicaid patients’ non-emergency trips on the back burner, given that without MCO contractual obligations she said they will likely favor trips for hospitals and nursing homes with which the ambulance companies have separate contracts.

MCOs have more flexibility to entice ambulance companies to prioritize rides for Medicaid MCO customers because they can use incentives like higher payments.

Illinois, through HFS’s fee-for-service model, cannot legally offer those incentives.

Pritzker’s press office cited similar concerns in a statement.

“Currently an enrollee in the medical assistance program needs non-emergency ambulance transportation, they can contact their MCO and the MCO’s transportation broker is contractually obligated to locate a ride in a timely fashion. If HB 684 is enacted, a consumer will be forced to use the vendor contracted with by the fee-for-services program — a vendor that is not contractually bound to provide timely services. Consumers would be forced into the uncertain position of not knowing which of their healthcare services are covered by their MCO, and whether they will be able to secure transport in a timely fashion,” the statement reads. “During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Department of Healthcare and Family Services (HFS) received consumer complaints regarding the difficulty of securing transport from their fee-for-service vendors to get to non-emergency healthcare services like check-ups and dialysis.”

Medicaid recipients are already suffering with the status quo, Vandenberg said.

“They’re talking about patients being endangered? What we’re talking about here is what really endangers patients: Not being able to get the ambulance services that you need when you need them,” he said. “So talking about those dialysis patients — if we’re not being paid by the managed care, we don’t have the ambulances that are able to provide the services to pick that patient up from dialysis, to take that patient to a radiation appointment, and the very scariest and real of senses, taking a patient that’s having a real emergency to a hospital.”

Fountain said it feels like emergency medical services are not getting the support they need, especially during a pandemic. He said Superior Ambulance Service had to secure its own masks and personal protective equipment for paramedics, as private ambulance companies weren’t included in state PPE distributions.

The EMT shortage is an ongoing and present medical concern, he said.

“We transport people from one hospital because that hospital doesn’t have the service that they need. This patient needs to go to a cath lab to have their heart opened up, but there’s a delay because there’s not an ambulance available because we don’t have the staffing. So somebody needs to be moved to a stroke center. And there’s a delay because there’s not an ambulance available. Time is tissue. The longer these people are waiting, the more damage that can be caused,” he said. “It affects the patient, the customer, the hospital, us.”

Not being able to move a hospital patient puts stress on the hospital system as the delta variant and lack of widespread vaccination has caused another surge in COVID-19 infections that’s leaving some hospitals without enough staff and bed space.

Staff shortages are not singular to Illinois, nor to the EMS industry, Eagleson said, though she said the agency is interested in exploring what to do about it.

Pritzker has until Saturday to act on the billing measure, or it will automatically become law.

His office has indicated he will not let that happen.

Though the statement doesn’t say so directly, the language used by his press office indicates a veto is likely.

“Initial analysis of HB684 shows this bill makes it less likely Illinoisans will have consistent access to qualify, affordable healthcare. The administration is concerned that this legislation has the potential to disrupt care and reduce the quality of provided services to some of the most vulnerable Illinoisans,” the statement reads.

Pritzker, a Democrat, has rarely used his veto pen on measures that make it to his desk only with the support of the Democrats who control the General Assembly.

Should he do it on the ambulance transport payment bill, the unanimous vote by the legislature indicates ambulance companies have the support they need in the General Assembly to override him.

Davis said the billing issues indicate compiling problems with the managed care model.

“Again, this bill passed both chambers unanimously. And that to me means that there is some issues with the MCOs in terms of how they’re working with different sectors. I would argue that not only are ambulances challenged with the MCO construct but also direct service providers are. Even hospitals are challenged with the MCO construct,” Davis said.

An examination of the MCO system is part of a health care law signed by Pritzker in April as part of the Black Caucus legislative agenda.

Follow Amanda Vinicky on Twitter: @AmandaVinicky