Editor’s Note: On Mar. 12, Microsoft President Brad Smith testified before the House Committee on the Judiciary, Subcommittee on Antitrust, Commercial, and Administrative Law.

Read Brad Smith’s written testimony below and watch the hearing here.

Written Testimony of Brad Smith

President, Microsoft Corporation

Chairman Cicilline, Ranking Member Buck, and members of the Subcommittee, thank you for the opportunity to appear today to discuss a critical issue for the country – the intersection between technology and journalism and its impact on the role of the press in our democracy.

We’re here today because technology is changing every part of our society. As an employee and leader at a tech company, I believe in the benefits that digital technology is creating for our country and the world. But we must recognize that technology is creating problems as well as benefits. And these problems require new and even urgent solutions, especially when they implicate values that are fundamental and even timeless.

There is no value that is more fundamental and timeless in our country than our commitment to democracy. There are few institutions more important to the health of democracy than a free press. And when technology undermines the health of the free press – as it has – then we must pursue new solutions to restore the healthy journalism on which our democracy depends.

New Challenges to the Critical Role of the Free Press

We meet today almost exactly forty years after a notable milestone in American journalism. On March 6, 1981, “CBS Evening News” anchor Walter Cronkite closed his legendary evening newscast with a final “That’s the way it is.” His signature sign-off encapsulated what he saw as news and journalism’s responsibility and obligation: to “hold up a mirror to tell and show the public what has happened.”

The news of Cronkite’s day was never short of controversy, including arguments between political leaders and journalists themselves. But in hindsight, the lines of the past seem less blurred than today between objective news, subjective opinions, and fiction. Walter Cronkite offered the country not just an evening newscast, but a primary set of shared facts that were debated at dinner tables and water coolers across the country. Before search engines, social media, and political websites, it was print and broadcast outlets that provided the nation with a baseline that shaped our understanding and the public sphere.

The importance of this broad dialogue and exchange of views took root in the 15th century with Johannes Gutenberg’s printing press, took off with the rise of newspapers and journals in 18th century Europe, and was carried across the Atlantic by our nation’s founders. The role of our nation’s free press was strengthened in 1735 when Andrew Hamilton successfully argued that his client, publisher John Peter Zenger, could not be imprisoned for seditious libel for critiquing the British government. This freedom was cemented a half century later in the First Amendment of the Bill of Rights.

Since our nation’s founding, the free and independent press has played a special role in supporting our democracy. It has served as a watch dog, monitoring, and challenging the issues and institutions that impact every facet of American politics and society. It’s the nation’s journalists who have pulled back the curtain on crime, corruption, excesses, inequality, and injustice – documenting every war since the American Revolution, the civil rights movement, Watergate, the Bay of Pigs, the dangers of pesticides, abuse in the Catholic Church, and the Flint water crisis, just to name a few.

But while national news grabs much of the glory, it’s the thousands of local news outlets that provide the foundation for local democracy across the country. As former House Speaker Tip O’Neill was fond of saying, “all politics is local.” American democracy flourishes or withers at the local level. And if one thing is clear, it is that local democracy requires local journalism. In 1835, Alexis De Tocqueville toured small communities across America and offered an observation about news organizations that remains true to this day: “To suppose that they only serve to protect freedom would be to diminish their importance: they maintain civilization.”

City boroughs, suburbs, and rural towns have long relied on local journalists to provide trustworthy information on the activities of City Hall, the school board, and the police station. Local newspapers have always held a special place in local communities, providing the bulk of our country’s original storytelling, producing more local reporting than television, radio, and online-only outlets combined.[1] According to a 2019 Nieman Lab’s study, while local newspapers account for just 25 percent of local media outlets, they pump out nearly 50 percent of original news.[2]

The sobering reality is that journalists and news organizations have struggled since Cronkite was deemed “the most trusted man in America.” As the 20th century turned into the 21st, the internet gutted the already ailing local news business by devouring advertising revenue and luring away paid subscribers.

The numbers paint a dire picture with newspaper circulation and advertisement revenue sharing the same downward spiral. Since 2000, ad revenue for newspapers has shrunk 70 percent, by $34 billion.[3] In the same timeframe, newspaper circulation has dropped by half, with 27 million fewer daily newspapers in circulation in 2018 than were published when the century started.[4] Since 2004, the U.S. has lost more than 2,100 newspapers.[5] In the last two years alone, 300 newspapers have closed, and print circulation declined by 5 million. And as the world has moved online, independent digital news sites have failed to fill the gap. While more than 80 local online sites were established in 2019, an equal number failed.[6]

With fewer and leaner newsrooms, opportunities for professional journalists are diminishing. According to a report by the University of North Carolina’s Hussman School of Journalism and Media, over the last decade the number of newspaper reporters has been more than halved, dropping from 71,000 in 2010 to 35,000 today.[7] And for writers and correspondents trying to make a living wage, annual salaries average just $37,000, slightly more than half the nation’s average salary for workers with a bachelor’s degree.[8]

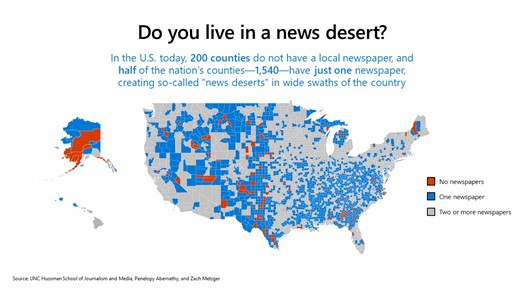

This alarming decline has left a gaping void in communities across the country. Today, half of the nation’s counties – 1,540 – are served by just one newspaper and 200 counties no newspaper at all.[9] Almost 70 percent of U.S. counties without a daily or weekly newspaper are outside of metropolitan areas,[10] creating so-called “news deserts.” Print media serving rural Native American communities alone plummeted from 700 outlets in 1998 to just 200 print media sources 20 years later.[11]

The remaining 6,700 American newspapers haven’t gone unscathed. Many survivors are “ghosts” of their former selves, operating on thin margins and skeleton staff. The COVID-19 pandemic has only accelerated the cuts and closures. As with many small businesses, the virus hit the media ecosystems hard as plunging revenue forced outlets at both the local and national level to make sweeping cuts. We’ve seen this firsthand in Microsoft’s home state of Washington, where virtually no newsroom was spared. Early in the pandemic, Sound Publishing, Adams Publishing Group, and EO Media Group announced layoffs, furloughs, and closures at local community papers. And just this week, Sinclair Broadcast Group, which owns and operates 186 stations across 87 markets in the United States, including Seattle’s KOMO-TV, announced that it would cut five percent of its workforce, potentially more than 400 people.[12]

When news organizations suffer, democracy suffers as well. A shortage of trusted reporters who hold government officials accountable has exacerbated issues at the local level. According to a study by University of Notre Dame and University of Illinois researchers, communities located in news deserts suffer from less competitive political campaigns, less informed voters, and lower voter turnout. Without reporters holding officials accountable, these communities also see higher public costs, with municipal borrowing costs increase by 5 to 11 basis points, costing municipalities an average of $650,000 more per issue.[13]

As news organizations struggle to create a financial model that supports healthy journalism, key questions loom large. Where will citizens get information on the local issues that affect them most? Without a pulse on the community around them, how can citizens fully participate and support a functioning society? And how will American democracy thrive where newspapers have vanished?

The Nature of Technology’s Impact

The accelerating crisis in news and journalism reflects the shift away from traditional advertising – i.e., television, radio, and print – to digital advertising, enabled by the emergence of the internet and fueled by behavioral data-based targeting. In 2020, spending in the U.S. on digital advertising reached $121 billion, accounting for 54 percent of the total spending on advertising.[14] Although news organizations embraced the internet by making their content available online, they fundamentally have not benefitted overall from the dramatic growth in digital advertising revenue. It’s impossible to address the economic challenges that ail journalism without assessing why this is the case.

While Google and Facebook have gained the most revenue from the shift to digital advertising, Google in multiple ways is unique. Google has been the biggest winner, capturing about a third of all digital advertising revenue in U.S. in the last year.[15] Indeed, since its founding just over twenty years ago, Google has grown its global ad revenue to approximately $147 billion.[16]

Google’s full impact, however, is based not on its large numbers but its multiple roles. Google accesses and uses news in a way that is different from Facebook. More important, it is the dominant technology firm in virtually every corner of the digital advertising ecosystem. It is impossible to understand fully the nature of technology’s impact on journalism without grasping these multiple roles. Because our businesses intersect at multiple points, we have first-hand insight into these dynamics.

Google began in 1998 as a search engine. It indexed the web and delivered – in response to a user query – a series of simple “blue links” that co-founder Larry Page said in 2004 aimed “to get you out of Google and to the right place as fast as possible.”[17] Its role in the world is very different today. Based in part on impressive ingenuity and innovation, Google today offers more than 60 consumer-facing properties, some of which are deservedly among the most popular in the world, including YouTube, Chrome, Google Maps, Gmail, and Google Drive. And its Android operating system – another impressive innovation – powers most of the world’s smartphones.[18]

The challenge for journalism arises from what comes next, which involves an extraordinary range of multiple pieces.

Google’s Search Ads. While it’s easy for anyone to publish content on the internet, it’s often hard to be found. Especially for a new or smaller entrant, the key is to be listed prominently in a search engine. Search engines display two principal types of results – links that are generated by algorithms and links that are purchased by businesses that buy ads. In contrast to two decades ago, an increasing share of what is shown on the first page in response to a search query is a set of links that were purchased as ads. In other words, businesses must pay to be found. This part of the market is hardly a hallmark of competition, as Google Search has generally had a market share between 80 and 90 percent for more than a decade.

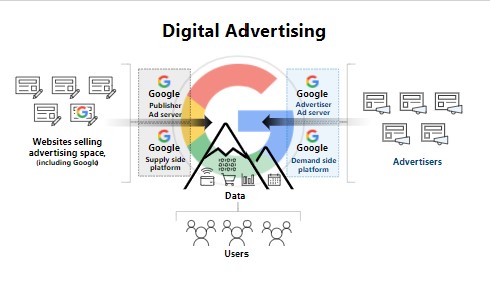

Google’s Ad Tech Business. What many outside the tech sector understand less well is that even after a user clicks off the search results page, Google continues to benefit from any advertising bought and sold on third party sites. This is because Google is the central player in virtually every aspect of ad sales for the entire web. Long gone are the days when advertisers bought advertising directly from television networks, radio stations, and news and other media publications. In the past two decades, sophisticated and pervasive tools and technologies – often referred to as “ad-tech” – have emerged and transformed the process of buying and selling advertising.

Google’s Ad Exchange. Advertising across the internet is no longer sold in person and instead is bought and sold electronically through centralized trading venues. These operate at high speed, much like stocks and bonds are at the New York Stock Exchange or NASDAQ. But unlike the stock exchange, the process is wholly unregulated. The largest such set of exchanges are all operated by Google. This means that even when a business, including a news organization, wants to buy an ad that will be placed on a third-party site virtually anywhere on the internet, it frequently must transact through Google’s exchange and pay Google a fee for doing so.

Google’s Ad Tech Tools. Because the ad exchanges are automated, firms must use digital tools to buy or sell advertising through them.[19] Google’s ad-tech tools are designed to work best with its own ad exchange, and this has helped them become and remain the most prevalent. Firms pay Google for the use of these tools as well. These tools provide buyers and sellers with a powerful capability to spend their money with enormous precision, based on the collection of comprehensive detailed information about individual users and the technology’s ability to enable advertisers to bid to display specific ads to those users as they travel across the internet.

Google’s Global Consumer Dataset. A final and fundamental piece that underlies all the others is an extraordinary and unparalleled dataset of detailed identifiable personal information about the consumers of the world. The operation of all the foregoing processes means that almost every website feeds information about user activity on its site back to Google, giving it unmatched data on user behavior and ad performance. That information is then used by Google services to improve targeting and the optimizing of ad campaigns.

This dataset also grows minute by minute from the billions of users engaging with Google’s search engine, its customer-facing properties and services like YouTube, and trackers it has deployed across the web. All this data is available through Google’s Ads Data Hub where advertisers can upload their own customer data and combine it with Google’s data to create more targeted advertising campaigns. But advertisers cannot take the resulting dataset out of the Hub unless it is exported to one of Google’s ad tech services. This reinforces Google’s central position in the digital advertising ecosystem.

As all this reflects and the chart below illustrates, Google’s digital advertising business encompasses the entire internet. It enables Google to aggregate the content of others, attract users, harvest their data, and then directly target them with ads at an unprecedented scale. None of this suggests that this vast network necessarily was built through unlawful action. But the extraordinarily expansive and interconnected nature of Google’s search and ad tech processes has few precedents in the history of the American economy.

The Implications for Journalism. The question for this hearing, of course, is the impact of all this on journalism. It is not a happy story, and it’s not just because the world has gone digital. News organizations have ad inventory to sell, but they can no longer sell directly to those who want to place ads. Instead, for all practical purposes they must use Google’s tools, operate on Google’s ad exchanges, contribute data to Google’s operations, and pay Google money. All this impacts the ability of news organizations to benefit economically even from advertising on their own sites.

But the problem has other dimensions as well. Ironically, Google’s business model is fed by the very content that these ailing news organizations create. As we know from our own experience with Microsoft’s Bing search service, timely, broad, and deep news coverage is critical to attracting users and strong engagement. It has real economic value.

More than a decade ago, when Google was far smaller and before it confronted antitrust inquiries, it acknowledged the same thing. In 2008, Marissa Mayer, Google’s former Vice President responsible for search and user experience, even put a price on that value. As Jon Fortt wrote for Fortune after listening to Mayer at a lunch session, “Google News funnels readers over to the main Google search engine, where they do searches that do produce ads. And that’s a nice business. Think of Google News as a $100 million search referral machine.”[20] As Fortt added, “Google is happy to build popular products that don’t make any money on their own but tie users into a broader Google ecosystem. It’s like Vegas casinos that offer cheap buffets to get people into the building, knowing a lot of them will end up playing slots.”[21]

A cursory glance at Google’s properties confirms that news is food that feeds its search and advertising network. A few years after it was founded, Google created its “news” section to supplement its core general search service.[22] Since then, Google has repeatedly invested engineering time and talent to improve the user experience and ensure that the content it displays is comprehensive, relevant, and timely. Today, news is one of Google’s top options on the menu bar immediately above search results. And, depending on the query, news results prominently populate the first page of search results in horizontal carousels as “Top Stories” and “Quotes in the News.” On Android and iOS mobile devices, where the bulk of digital advertising revenues are earned today,[23] a personalized feed of news articles is featured immediately below the search bar on the home page of the Google Search and Google Chrome applications. There is a reason so much of the internet’s most valuable real estate is dedicated to news.

Even though news helps fuel search engines, news organizations frequently are uncompensated or, at best, undercompensated for its use. Google and others are quick to point out that news organizations get referral traffic from their properties, seeming to suggest that on the vast internet, news organizations should be grateful simply to be found.

While it’s important to recognize that referral traffic does have value, monetizing that traffic has become increasingly difficult for news organizations because most of the profit has been squeezed out by Google. Google has effectively transformed itself into the “front page” for news, owning the reader relationship and relegating news content on their properties to a commodity input.[24]

Ultimately, the contrast could hardly be starker. As Pew Research estimates, the advertising revenue of the nation’s newspapers fell from $49.4 billion in 2005 to $14.3 billion in 2018. During this same time, Google’s advertising revenue rose from $6.1 billion to $116 billion. [25] This is not a coincidence.

What Should Be Done?

Because the challenge is so complex and extensive, the cure will likely require a variety of prescriptions. This is a topic we’ve been thinking about at Microsoft for some time. It’s also one we’ve explored more deeply since Google threatened to pull its search service out of Australia and put us in the position of asking how we could fill the resulting void in a way that better served that nation. We all clearly have more to learn from each other, but at this point three conclusions rise to the top.

First, like all businesses, journalism must continue to evolve. No industry can flourish without change, especially in an era dominated by dynamic technology. The principles underlying a free market call on all of us always to ask ourselves how we can better serve our customers. The news business, like any business, is subject to market economics. From everything we’ve seen, the leaders of news organizations large and small recognize this, and we’re encouraged by the spirit of innovation that so many of them are bringing to this challenge.

Indeed, there are some promising signs that the news industry is transforming and some in it are beginning to find new sustainable models. Marque publications from well-known news organizations – such as the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, and the Washington Post – are experiencing growth. In recent years, they have created compelling digital-first experiences sustained through a healthy and growing subscriber base and diversified their businesses, extending into adjacent areas, like events. Others – like Axios and Politico – are finding success by launching email and online newsletters or podcasts, offering a personality-driven or specialized point of view on an industry or topic, to interested subscribers.

Second, news today is part of the technology ecosystem, and all of us who participate in this ecosystem have both an opportunity and responsibility to help journalism flourish. In short, tech companies need to do more.

We recognize that we should start with ourselves, and this too requires a multifaceted approach.

Our Microsoft News app and website now provide content from more than 1,200 publishers to nearly 500 million readers globally each month. Supported by advertising, we are committed to healthy revenue-sharing with news publishers. As we announced last year, this has provided more than $1 billion to news publishers since 2014. We are committed to continued work to grow the reach of this service and sharing revenue broadly with publishers.

We also recognize the need to look beyond our Microsoft News service and consider additional new and even out-of-the-box commercially-viable ideas to help promote healthy journalism. We are committed to doing this, and we’re exploring new ideas privately with publishers. This includes the way our Bing search service interacts with and supports news organizations.

We’re also committed to measures that take us beyond traditional business initiatives. Last year Microsoft launched a new journalism initiative.[26] It has three parts: helping local news organizations put in place new revenue streams and funding models for the future; ensuring the integrity and authenticity of news by fighting against deep fakes and the like; and protecting the security of journalists, both in the U.S. and abroad. We now have five pilot programs up and running around the country: in Seattle and Yakima, Washington; Fresno, California; the El Paso, Texas and Juárez, Mexico region; Jackson, Mississippi; and the Appleton and Green Bay, Wisconsin communities. We are bringing our technical expertise to these community newsrooms and are partnering with other industry organizations and foundations to share expertise and experience that will further expand the reach and impact of the initiative.

We’re also working domestically with the Reporters Committee for the Free Press and the Davis Wright Tremaine law firm to provide pro bono legal services for journalists. And we’re working globally with the Clooney Foundation for Justice to ensure a fair trial and human rights protection for journalists who are prosecuted d by authoritarian governments.

Third, we need the government to act. This in part is because of the indispensable role the free press plays in our democracy and because progress in resuscitating news and journalism back to health is, at best, spotty. It is also because the problems that beset journalism today are caused in part by a fundamental lack of competition in the search and ad tech markets that are controlled by Google. As a result, there is a persistent and structural imbalance between a technology gatekeeper and the free press, particularly small and independent news organizations. This makes it very unlikely that the economic transformation needed to restore journalism to health can succeed at scale without new legislation and government support.

As noted above, this is not to make a statement about whether Google has acted unlawfully. We respect the company’s sustained creativity, investments, and determination. But as we learned first-hand from Microsoft’s own experience two decades ago, when a company’s success creates side effects that adversely impact a market and our society, the problem should not be ignored. And this typically requires government action.

This is what led the Australian government to enact new legislation last month. The idea there was straight-forward: the Australians put in place legislation to help drive market-based solutions. It kicks in only when a tech gatekeeper – designated by the government – is unwilling or unable to reach agreements on its own with independent news organizations to compensate them for the benefit it derives from the inclusion of news content on its platform. The legislation – when applied – mandates that a designated tech gatekeeper negotiate in good faith. News organizations can join for purposes of collective bargaining; allowing them to pool their resources and improve their bargaining power. And, in the event of an impasse, the legislation requires arbitration to break a deadlock.

The Australian approach is proving effective at driving negotiations. As the legislation was poised for adoption, Google threatened to pull its search service out of the country. But when we announced that Microsoft Bing – its primary competitor – would remain and, if it grew in Google’s absence, would comply with the legislation,[27] Google immediately flip-flopped. Within 24 hours, Google was on the phone with the Prime Minister, saying it wouldn’t leave the country after all. And in the two weeks that followed, Google accomplished something it claimed impossible just a few days before: it negotiated agreements with the three largest news organizations in Australia, reportedly valued at more than $100 million.[28]

All these issues highlight not just the propriety but the importance of consideration by a congressional committee responsible for antitrust and commercial law. As this committee considers its focus near the start of a new Congress, we believe there are a few issues that are especially worthy of consideration:

- Move forward with the Journalism Competition and Preservation Act and enable news organizations to negotiate collectively with online content distributors. We endorse this legislation with full recognition that Microsoft likely would be designated as an online content distributor subject to it. This is because, under the legislation’s proposed terms, we have more than a billion monthly active users, in the aggregate, for all our websites and online services worldwide. Hence this legislation would increase the ability of news organizations to negotiate collectively with us as well as others.

We nonetheless believe that this legislation would advance a critical need by enabling more effective bargaining by smaller news organizations that are critical to sustaining local news across the country. Antitrust immunity that enables small publishers to negotiate collectively is not in any practical sense a departure from the principles that underlie the nation’s competition laws. To the contrary, this change is essential to advance the type of market competition that our antitrust laws were enacted to support.

- Add to the proposed Journalism Competition and Preservation Act by imposing additional obligations on online content distributors. The Congress should review closely other terms in Australia’s recent law and incorporate elements from it. For example, this should include transparency requirements, an obligation to negotiate in good faith, and a duty to avoid retaliation. It should also provide a level of oversight and monitoring by an agency such as the FTC.

To be clear, we’re sensitive to the argument that we must avoid enacting a law that would “break the internet.” We would not have endorsed the Australian law if we believed there was any real merit to Google’s argument that the country’s legislation would have done that. As we studied Australia’s legislation closely, we concluded that there was no foundation for the fear that people would have to “pay per link” to use the internet. This was confirmed explicitly when the final legislation affirmed explicitly what was apparent to us as soon as we studied the earlier drafts, namely that publishers could be paid through lump sums rather than “by the link.” (Ironically, the most prevalent place on the internet where people today pay per link is on search engines themselves, where this is applied to ad-sponsored links.)

- Consider new legislative and regulatory codes to restore competition to the search and ad tech markets. One of the clear lessons from Australia’s recent experience is the need for more competition in the market itself. It’s not good news for democracy when a company as large as Google threatens to boycott a nation with more people than Florida if its elected legislators pass something it doesn’t like. One of the lasting questions from Australia is whether Google would have ever retreated from its threats if Microsoft hadn’t stepped forward with a promise to replace it. This is not the type of question that other states or countries should be forced to confront.

This requires new steps to bring back competition to the search and ad tech markets. This is not to offer an opinion on what antitrust enforcement agencies should do. Rather, it’s to suggest that Congress consider what it can do. For example, in the 1980s the authorities in the United States and Europe addressed dominant control of airline computer reservation systems by enacting codes of conduct that protected airline passengers by ensuring effective choices in learning about flights and fares. In a similar way, the United Kingdom and the European Commission today are addressing a lack of competition in key technology markets through new laws and regulatory oversight. In short, there is a potential future role for Congress that is worthy of consideration.

Clearly, Microsoft has its own commercial interests here, and we would be less than forthright if we failed to acknowledge them. But we would also point out that some of the foregoing ideas run against our own interests, while others might benefit them.

At the end of the day, however, this should not be a conversation about what these ideas mean for the interests of a particular tech company. Instead, the ultimate question is what values we want the tech sector and independent journalism to serve. We have been consistent in saying that this is a defining issue of our time that goes to the heart of our democratic freedoms. As we wrote in 2019, “The tech sector was born and has grown because it has benefited from these freedoms. We owe it to the future to help ensure that these values survive and even flourish long after we and our products have passed from the scene.”[29]

More than ever, Congress must help define where and how technology and journalism should intersect.

[1] Jessica Mahone, Qun Want, Philip Napoli, Mathew Weber, and Katie McCollough, “Who’s Producing Local Journalism: Assessing Journalistic output Across Different Outlet Types,” The News Measures Research Project, August 2019, https://dewitt.sanford.duke.edu/whos-producing-local-journalism-nmrp-report/.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Pew Research Center, “Journalism and Media: Newspapers Fact Sheet,” July 9, 2019, https://www.journalism.org/fact-sheet/newspapers,/

[4] Ibid

[5] Penelopy Abernathy and Zach Metzger, “News Deserts and Ghost Newspapers: Will Local News Survive?” UNC Hussman School of Journalism and Media, June 2020, https://www.usnewsdeserts.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/2020_News_Deserts_and_Ghost_Newspapers.pdf.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Reporters, Correspondents, and Broadcast News Analysts,” March 6, 2021, https://www.bls.gov/ooh/media-and-communication/reporters-correspondents-and-broadcast-news-analysts.htm – tab-6/.

[9] Abernathy, et. al.

[10] Clara Hendrickson, “Critical in a public health crisis, COVID-19 has hit local newsrooms hard,” Brookings, April 8, 2020, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/fixgov/2020/04/08/critical-in-a-public-health-crisis-covid-19-has-hit-local-newsrooms-hard/.

[11] Jodi Rave, “American Indian Media Today,” Democracy Fund, November 2018, http://democracyfund.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/2018_DF_AmericanIndianMediaToday.pdf.

[12] Heidi Groover, “KOMO Lays Off Employees Amid National Cuts at Sinclair,” Seattle Times, March 7, 2021, https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/komo-lays-off-employees-amid-national-cuts-at-sinclair/

[13] Pengjie Gao, Chang Lee, and Dermot Murphy, “Financing Dies in Darkness? The Impact of Newspaper Closures on Public Finance,” Journal of Financial Economics, 135:2, 445-467 (2020).

[14] PwC, “Global Entertainment & Media Outlook 2019-2023” (available at https://www.pwc.com/us/en/industries/tmt/library/global-entertainment-media-outlook.html).

[15] See eMarketer, Net Amazon, Facebook, and Google Ad Revenue in the US 2019 and 2020 (June 2020) and US YouTube Net Ad Revenues 2019-2020 ((October 2020) (available at www.emarketer.com).

[16] See Alphabet, Inc., Form 10-K at 33 (for fiscal year ending Dec. 31, 2020) (available at https://abc.xyz/investor/static/pdf/20210203_alphabet_10K.pdf?cache=b44182d).

[17] Amendment No. 9 to Form S-1 for Google, Inc. at B6 (Aug. 18, 2004) (available at https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1288776/000119312504142742/ds1a.htm).

[18] See IDC, “Smartphone Market Share” (Dec. 15, 2020) (Android smartphone shipments in 2020 forecasted to comprise 85 percent of all shipments) (available at https://www.idc.com/promo/smartphone-market-share/os).

[19] These services and tools include those used by advertisers to manage their digital ad campaigns and to buy ad inventory programmatically from publishers as well as those used by publishers to sell their advertising space and to organize and manage the ad inventory on their websites.

[20] Jon Fortt, “What’s Google News Worth? $100 Million,” Fortune (July 22, 2008), https://fortune.com/2008/07/22/whats-google-news-worth-100-million/).

[21] Ibid.

[22] Krishna Bharat, “And Now, News” (Jan. 23, 2006) (available at https://googleblog.blogspot.com/2006/01/and-now-news.html).

[23] See, “Digital News Fact Sheet,” Pew Research Center (July 23, 2019) (“…in 2018, mobile advertising revenue comprised almost two-thirds (65%) of all digital advertising revenue.”) (available at https://www.journalism.org/fact-sheet/digital-news/).

[24] See, e.g., Barthel supra “ (“Time spent on [news] websites has declined as well: The average number of minutes per visit for digital-native news sites is down 16% since 2016, falling from nearly two and a half minutes to about two per visit. The decreases in website audience and time spent per visit come as Americans increasingly say they prefer social media as a pathway to news.”).

[25] Pew Research Center, “Journalism and Media: Newspapers Fact Sheet,” July 9, 2019, https://www.journalism.org/fact-sheet/newspapers,/; Google, Inc., Form 10-K at 48 (for the fiscal year ending Dec. 31, 2005) (available at https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/0001288776/000119312506056598/d10k.htm; Alphabet, Inc., Form 10-K at 27 (for the fiscal year ending Dec. 31, 2018) (available at https://abc.xyz/investor/static/pdf/20180204_alphabet_10K.pdf?cache=11336e3.

[26] Mary Snapp, “New Steps to Preserve and Protect Journalism and Local Newsrooms,” Microsoft on the Issues, October 7, 2020, https://blogs.microsoft.com/on-the-issues/2020/10/07/local-news-pilot-accountguard-defending-democracy/.

[27] Brad Smith, “Microsoft’s Endorsement of Australia’s Proposal on Technology and the News,” Microsoft on the Issues (Feb. 11, 2021) (available at https://blogs.microsoft.com/on-the-issues/2021/02/11/endorsement-australias-proposal-technology-news/).

[28] Max Mason and John Kehoe, “Nine Signs Google Deal, Guardian and ABC Near Completion” Financial Review (Feb. 17, 2021) (available at https://www.afr.com/companies/media-and-marketing/nine-and-google-strike-30m-news-deal-20210217-p5737j).

[29] Brad Smith and Carol Ann Browne, Tools and Weapons: The Promise and the Peril of the Digital Age (New York: Penguin Press, 2019), 304.