This blogpost is one of three from Professor Becky Allen, Professor John Jerrim and Dr Sam Sims, reporting findings from Nuffield Foundation-funded research they have conducted into teacher mental wellbeing. It reports new findings based upon recently collected data from the Teacher Tapp survey app. The full report is available here.

We began the 2019/20 academic year collecting regular data on teacher wellbeing to find out how it rises and falls over the course of a typical year. Little did we know how atypical this year would be!

However, while events have prevented us from learning how teacher wellbeing is affected by regular annual events, such as the public examination cycle, we did find ourselves in the unique position of being able to observe how teachers responded to the COVID-19 lockdowns.

In this series of three blogposts, we describe how our research project has helped us learn a little more about the nature of teacher mental wellbeing.

A single measure of work-related anxiety

Unlike some other professions, teachers face quite a predictable pattern of work-related stresses during the year, thanks to the cycle of terms, holidays, and examination and results seasons. However, researchers have not yet measured how teachers in England respond to these events.

Since October 2019, we repeatedly asked a single question about an aspect on wellbeing that is fairly sensitive to short-term life events throughout the academic year:

On a scale where 0 is “not at all anxious” and 10 is “completely anxious”, overall, how anxious did you feel about work today?

We asked over 8,000 teachers this question at 3:30pm on a Tuesday, a time when work-related anxiety is relatively high for classroom teachers (it peaks on Monday and falls through to Saturday afternoon, before rising again).

This may explain why our sample reported fairly high anxiety levels relative to the Annual Population Survey (e.g. during term-time 36% of teachers report an anxiety value of 6-10, versus just 20% in the population).

Though it is just a single question trying to capture a relatively complex construct, we were able to show that our anxiety score was closely correlated with other broader measures of mental wellbeing, such as the Warwick-Edinburgh scale and relevant questions in the Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey (more on this in our next blogpost).

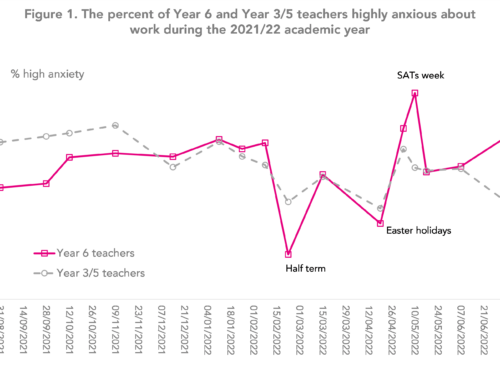

We could also observe how work-related anxiety falls during a half-term holiday, with around 13% of teachers typically reporting very high work-related anxiety during term time and just 5% during the holiday week.

The typical school year suddenly becomes very atypical

In mid-March, schools were required to close to all children, except for those from key-worker and vulnerable families. While this meant that many of our original research questions could not be pursued, we could report on work-related anxiety as the nature of work radically changed.

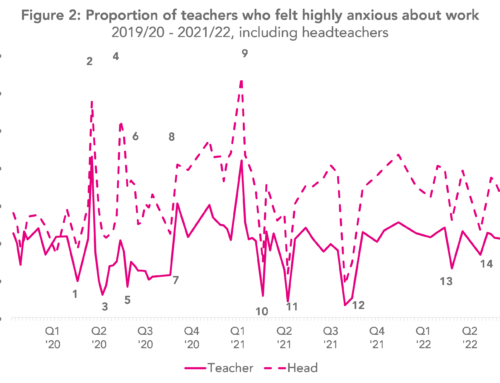

The chart below shows the proportion of teachers reporting very high work-related anxiety on a Tuesday throughout the academic year.

The impact of the pandemic is stark. In the week before schools were asked to close, anxiety levels peaked as teachers tried to cope with high staff absence rates, emergency closures, worry about infection and uncertainty about the future.

Headteachers had a very different experience of work throughout lockdown, managing a number of novel complex administrative and pastoral tasks.

Their duty of care towards their staff and students, especially the vulnerable ones, became necessarily hard to manage.

We saw their anxiety levels peak in the week before closure and again when the plans to re-open schools to new year groups were announced.

It was noticeable that their anxiety often rose in response to rumours rather than policy changes: for example, it rose on 21 July in response to the media leaking the plans for September re-openings, which were then announced towards the end of the week.

This extended period of stress for headteachers, which has extended throughout school holidays, may have long-term consequences for retention.

Towards the end of June, one-in-five heads felt that the experience has made it more likely that they will seek to leave the profession – see the chart below.

While moving professions is particularly difficult during an economic downturn, those heads who are closer to retirement might be in a position to choose to leave earlier than planned.

Online ‘live’ instruction is stressful

During lockdown, the experiences of classroom teachers in the state versus private sector diverged considerably.

In ‘normal’ times we found that private school teachers tend to report lower work-related anxiety than those in the state sector, but this switched during lockdown.

Whereas state school teachers generally reported much lower anxiety during lockdown than in the pre-lockdown period, the anxiety of private school teachers rose considerably.

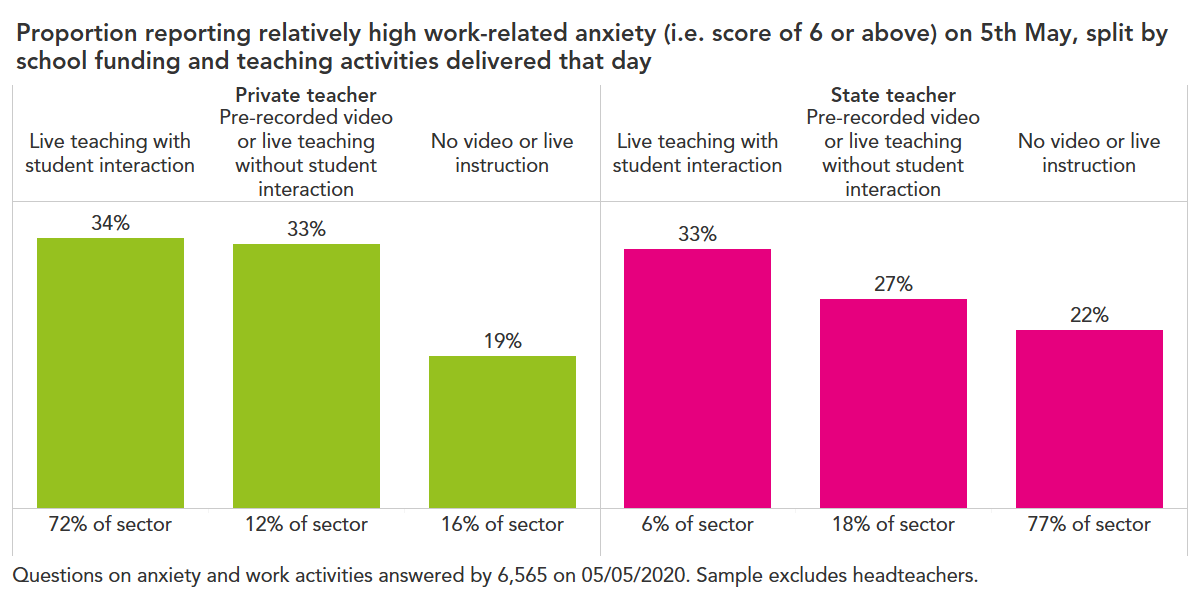

During this time, private school teachers were far more likely to running ‘live’ online teaching each day, compared to teachers in state-funded schools. For example, on 5 May, about three-quarters of private schools said they had hosted an online ‘live’ lesson where students were able to interact; in state schools just 1-in-20 had.

Importantly, we also found there to be differences in anxiety levels depending upon whether live/video instruction was provided by teachers or not. For instance, around a third of teachers (both private and state) who delivered live/video instruction to pupils during lockdown were highly anxious. In contrast, of those teachers who did not provide live/video instruction, high anxiety levels were only observed in around one-in-five

This may go some way to explaining the private/state difference in anxiety levels during lockdown – private school teachers were much work likely to deliver live/video teaching – which is a stressful activity.

Figures along the horizontal axis refers to the percentage of teachers delivering that form of instruction (e.g. 72% of private school teachers delivered live teaching with student interaction). Figures above the bars refer to the percent of teachers with high-levels of work-related anxiety (e.g. 34% of private school teachers who delivered live teaching had high levels of work-related anxiety).

That said, these levels of anxiety are actually quite similar to the levels reported by teachers earlier in the year before lockdown.

Stress associated with going into school fell over time

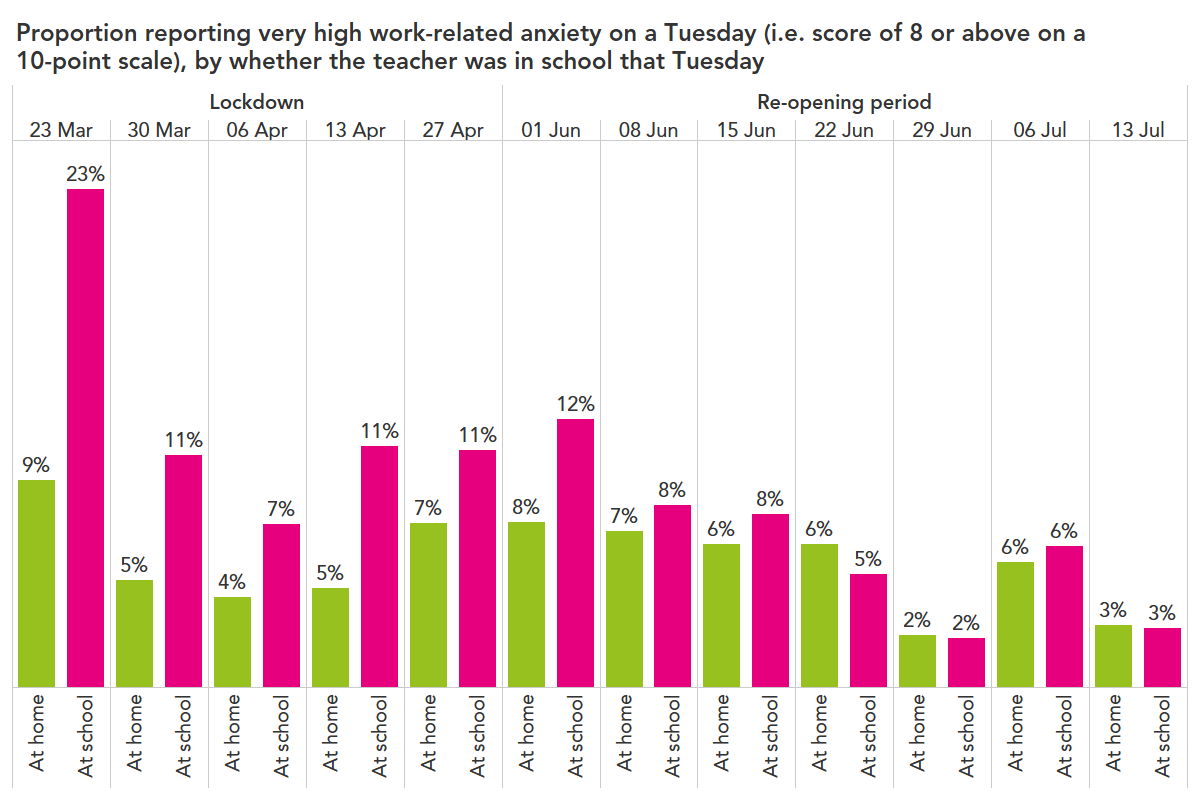

During lockdown, we knew whether a teacher was in school or not each day, so were able to see how being in school affected anxiety levels.

At the very start of lockdown, teachers who went into school to look after key-worker and vulnerable children reported much higher anxiety than those at home.

While this pattern of higher anxiety for those working in schools persisted, the differences gradually became less stark – see the chart below.

By the end of June when most teachers had regularly spent time in school again, there were no difference in anxiety levels reported between those who were, and were not, in school.

Lessons learnt

What conclusions can we draw from this work?

Overall, while work-related anxiety rose for headteachers and (to a lesser extent) private school teachers, lockdown was not generally associated with higher work-related anxiety for state school classroom teachers.

Of course, work-related anxiety is just one narrow aspect of mental wellbeing. In the next blogpost in this series, we will explore whether lockdown was damaging for teachers’ psychological wellbeing overall.

Now read the next post in this series.

The project has been funded by the Nuffield Foundation, but the views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily the Foundation. Visit www.nuffieldfoundation.org.

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from FFT Education Datalab? Sign up to Datalab’s mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive the team’s half-termly newsletter.

Leave A Comment