The IPO parade that has continued in 2021 is not a strictly domestic affair. Other countries are getting in on the unicorn liquidity rush.

This week, India-based food-delivery unicorn Zomato filed to go public. As TechCrunch reported, the company intends to list “on Indian stock exchanges NSE and BSE.”

The Zomato IPO is incredibly important. As our own Manish Singh reported when the company’s numbers became public, a “successful listing [could be] poised to encourage nearly a dozen other unicorn Indian startups to accelerate their efforts to tap the public markets.” So, Zomato’s debut is not only notable because its impending listing gives us a look into its economics, but because it could lead to a liquidity rush in the country if its flotation goes well.

The Exchange explores startups, markets and money. Read it every morning on Extra Crunch or get The Exchange newsletter every Saturday.

At this point, we’ll pause and note that India is currently enduring a COVID-19 surge that may be without precedent. You can provide help here. May the pandemic abate quickly and with as little pain as possible.

Back to Zomato: The company’s IPO filing paints the picture of a quickly growing company derailed by the pandemic. However, the unicorn has posted rapid recovery in recent quarters, and its economics are maturing to the point when it can begin to craft a path to long-term profitability. This morning, let’s dig into its numbers and try to sort out why the company is going public now and how investors may vet its recent performance.

Zomato’s business

Zomato was last valued at around $5.4 billion in a February 2021 round that put $250 million into its operations. The unicorn has raised more than $2 billion to date, per Crunchbase data.

In business terms, Zomato offers more than merely food delivery. Per its IPO filing, the company’s food delivery business is supplemented by its “dining-out” capability that facilitates in-person eating, a raw materials business called “Hyperpure,” and Zomato Pro, a consumer offering that provides food discounts to its 1.4 million subscribers.

So we can’t merely compare the firm to, say, Uber Eats — the India operations of which Zomato bought back in the day — on a one-to-one basis.

But what we can track is the company’s aggregate financial performance through the end of 2020. The Zomato filing does not appear to include information regarding the company’s calendar Q1 2021 performance; that period, for reference, is the fourth quarter of the company’s fiscal 2021.

Let’s start from a very high level:

- Fiscal year ending March 31, 2019: $187.4 million in total revenue, and a loss before exceptional items of $296.3 million.

- Fiscal year ending March 31, 2020: $367.8 million in total revenue, and a loss before exceptional items of $303.5 million.

- Nine-month period ending December 31, 2020: $183.4 million in total revenue, and a loss before exceptional items of $47.8 million.

Zomato grew quickly during its fiscal years ending March 31, 2019 and 2020. It did a less impressive job lowering what is perhaps comparable to its operating losses. But then what the hell happened in the rest of calendar 2020? Did the company shrink?

Yep, it did. But the company’s losses also dipped, so we’ve entered the fun territory of weighing plusses and minuses.

To catch us up on what the pandemic did to Zomato, let’s observe its quarterly results, keeping in mind that its fiscal 2021 started in calendar Q2 2020:

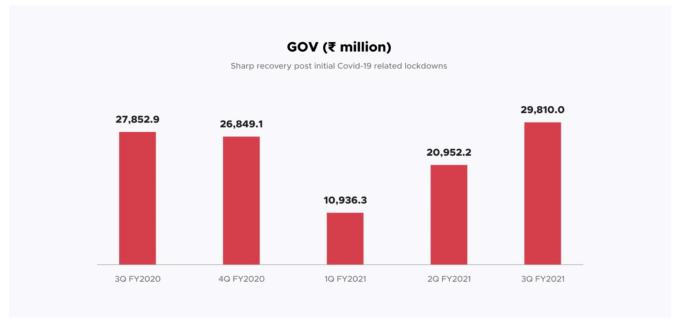

Image via Zomato filing

COVID-19 initially cut Zomato in half in terms of gross order volume. That’s a brutal result.

However, the company has since bounced back, posting what its prospectus describes as “GOV growth of 91.6% and 42.3% in the second and third quarters of Fiscal 2021 respectively, over the immediately preceding quarters.” And that final GOV result in Q3 of fiscal year 2021, or the fourth calendar quarter of 2020, was the company’s best ever. (“Our GOV in the third quarter of Fiscal 2021 was ₹29,810 million, which was the highest GOV that we have achieved in any quarter till December 2020,” per Zomato itself.)

This chart helps explain the timing of the Zomato IPO; the company is going public not on the back of consistent historical growth, but on a rocket ship recovery from pandemic-induced lows.

Yes, you are saying, but because the company was growing nicely before and was still setting fire to huge bales of cash, what good is a post-COVID recovery when its business is such hot garb? Aha! A good question. The good news for Zomato and its backers is that its economics have recently turned around.

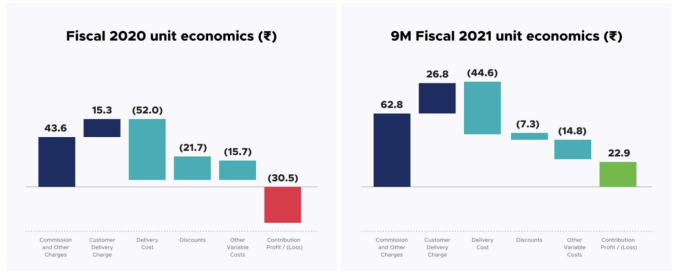

Here are two charts detailing the unit economics that Zomato recorded in its fiscal 2020 (the 12-month period ending March 31, 2020) and the first three quarters of its fiscal 2021 (the nine-month period ending December 31, 2020):

Image via Zomato filing

What changed that shook Zomato’s business from comically poor to something that looks pretty darn strong? The following:

- Rising commission per order, from ₹43.6 to ₹62.8, or +44%.

- Rising customer delivery charge per order, from ₹15.3 to ₹26.8, or +75%.

- Modest improvements to delivery costs.

- Falling discounts per order, from ₹21.7 to ₹7.3, or -66%.

- Modest improvements to variable costs.

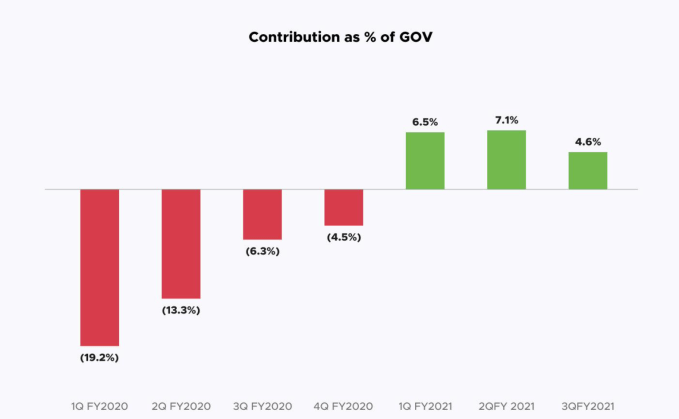

Put simply: a holistic improvement to pretty much every part of its unit economics. The impact of the changes is dramatic. The following chart tracks the swap from negative contribution to positive that Zomato has managed in recent quarters:

Image via Zomato filing

Now, that final quarter’s decline is not so good and could worry some investors about the long-term trajectory of Zomato’s contribution margin as a percent of GOV. But, when we combine the company’s rapid COVID-19 order recovery and its improving economics, the company can make a pretty good pitch that it has a path out of red ink and into the black.

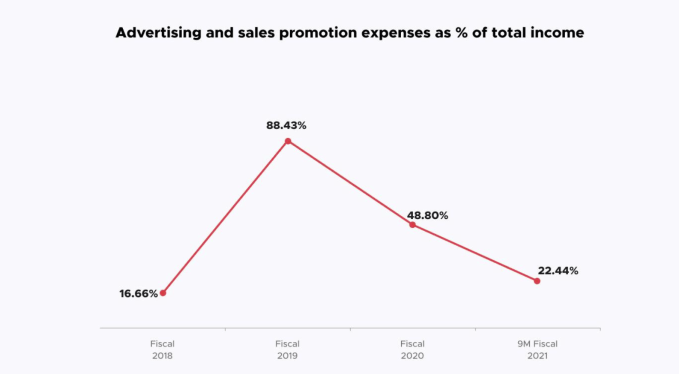

To better show how extreme the improvements to its economics had to be to get the company into the better profit territory that we’re discussing, observe the following chart:

Image via Zomato filing

You can see the “investment” period there in fiscal 2019, and the resulting reduction in promo spend as a percentage of revenue over time. A good question is this: How much more can the company push down that ratio? Every rupee not spent on promotional costs is a rupee that could wind up helping the company end its history as a cash-burning entity.

Speaking of which, Zomato’s cash burn has also fallen in recent quarters. From a simply staggering operating cash burn of $287.9 million in its fiscal 2020 to just over $36 million in the final nine months of 2020, the company’s improving unit economics have hugely cut its cash appetite. It’s still not self-sustaining, but the company’s operations really have improved.

Let’s close with some questions:

- Can Zomato sustain the changes to its economic model that could have been helped by COVID; i.e., will consumers still be willing to pay higher fees once the pandemic subsides?

- Will the tragic COVID-19 surge reduce demand for Zomato services in the coming quarters enough to derail its recovery story?

- Can the company manage to keep growing at a rapid clip while sustaining its improved unit economics in the coming years?

How you answer those questions will help determine how hyped you are for the Zomato IPO. But regardless of our views, the market’s judgment of the company matters for so many other unicorns and startups that we have no choice but to truly give a fuck.