The mere mention of the phrase “translational gap” can bring shivers down the spine of basic researchers and clinicians alike. The use of this term is meant to capture the magnitude of the task of transforming any understanding of how the nervous system functions to its realization as a therapeutic intervention or available technology in a human population. No investigator is more vulnerable to the sleep-depriving capabilities of this proverbial ‘boogey-man’ than one who focuses on neuropsychiatric disorders and, more broadly, mental health.

As of today, the level of resolution and specificity with regards to tools stand in opposition with the model organisms that may provide the most neurobiological similarity. Working with rodents offers the incredible advantages of genetic and viral manipulation, single cell monitoring and imaging capabilities, a modest behavioral repertoire, and (maybe most importantly) the access to all of these techniques in a mammalian brain. However in spite of all these attractions, the cognitive character of neuropsychiatric disorders and mental health make the translational gap separating insights gained from the rodent nervous system and their application to clinical populations dauntingly vast. Credit: B. MELLOR

Credit: B. MELLOR

Dr. Jyoti Mishra, founder of the Neural Engineering and Translation Labs (NEATLabs) at UCSD, employs a highly collaborative and interdisciplinary approach to help bridge the gap. By leveraging the latest monitoring and neural-interfacing technologies, Dr. Mishra examines the relationship between the neural activity of human subjects (measured using mobile cognitive assessment tools, EEG and fMRI) with more invasive and small-scale circuit manipulation in rodents in response to homologous sets of behavioral assays designed to assess neural and cognitive function. By this ‘translational transitive property’ a link can be drawn between circuit manipulations which give rise to any given cognitive or neural change as measured by a particular test and their accompanying neural fingerprint present in human subjects displaying similar responses to that test.

In her 2014 paper Dr. Mishra examines the phenomenon of aging and its association with deficits in the ability to ignore distractions. In this study she developed a targeted cognitive training intervention designed to train older rats and older humans to be able to filter out increasingly disruptive distractions. This is distinct from older tests formulated in efforts to recovery this age related decline in attention in that instead of modeling the task around training the subject to focus on increasingly subtle task-relevant stimuli, Dr. Mishra focused exclusively on the ability to ignore distractions. This may seem like a case of semantics, but the neurobiology says otherwise. There has been work to show that the circuits underlying neural enhancement and neural suppression are distinct (Chadick and Gazzaley, 2011). It follows that, unsurprisingly, cognitive training regiments targeted at stimuli-identification did not improve the deficiencies in distraction suppression displayed by older populations.

Mishra, Gazzaley, et al. 2014

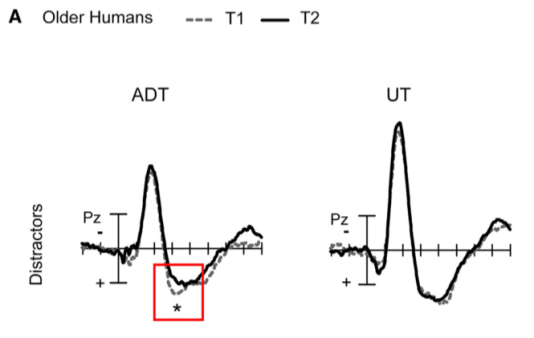

Shown above are the differences in responsiveness of neurons in the Auditory Cortex of rats both trained (ADT) and untrained(UT). The right graph shows a marked suppression of neural activity correlated with distractors, while the response to the task-relevant auditory cue (Oddballs) is unaffected. Shown below is the corresponding data from a cohort of older humans, showing a similarly selective suppression of neural activity in response to distractors. The dotted line shows neural responses in the auditory cortex at the beginning of training and the solid line represents a performance at the end of training regiment.

Mishra, Gazzaley, et al. 2014

This inter-species approach to developing potential therapeutic interventions as well as elucidating the circuitry at work is an essential characteristic of Dr. Mishra’s approach to her work. This conceptual framework also serves as the foundation on which NEATLabs operates as they continue to make strides towards bridging the translational gap.

To hear more about the work being done in Dr. Mishra’s lab, please join us at 4:00pm, Tuesday 10/15/2019 at the Marilyn G. Farquhar Seminar Room.

Blogpost written by Peter Fenton: 1st year Neurograd Ph.D student currently rotating in the Spitzer Lab studying neurotransmitter switching.