Europe's Cheops telescope begins study of far-off worlds

- Published

Europe's newest space telescope has begun ramping up its science operations.

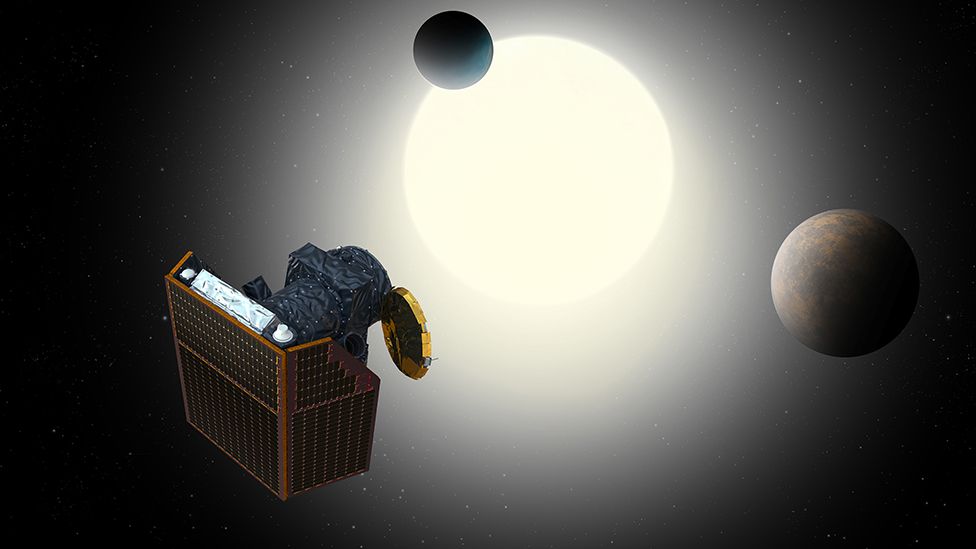

Cheops was launched in December to study and characterise planets outside our Solar System.

And after a period of commissioning and testing, the orbiting observatory is now ready to fulfil its mission.

Early targets for investigation include the so-called "Styrofoam world" Kelt-11b; the "lava planet" 55 Cancri-e; and the "evaporating planet" GJ-436b.

Discovered in previous surveys of the sky, Cheops hopes to add to the knowledge of what these and hundreds of other far-flung objects are really like.

The Swiss-led telescope will do this by watching for the tiny changes in light when a world passes in front of its host star.

This event, referred to as a transit, will betray a precise diameter for the "exoplanet". When this information is combined with data about the mass of the object - obtained through other means - it will be possible for scientists to deduce a density.

And this should say a lot about the composition and internal structure of the target.

Kelt-11b has provided a good early demonstration. This is a giant exoplanet some 30% larger than our own Jupiter that orbits very close to a star called HD 93396. Kelt-11b is a seemingly "puffed up" world with a very low density - hence the comparison with expanded foam.

From the way the light from the star dips when Kelt-11b moves in front to make its transit, Cheops' exquisite photometer instrument is able to determine the planet's diameter to be 181,600km (plus or minus 4,290km). This measurement is over five times more precise than was possible using a ground-based telescope.

The European Space Agency (Esa) is part of the collaboration behind Cheops. Its project scientist Dr Kate Isaak lauded the performance of the new observatory.

"We have a very stable satellite; the pointing is excellent - better than requirements. And this is going to be a real benefit to the mission," she told BBC News.

"From the spacecraft side, from the instrument side, from the analysis of the data that we're getting - we can see that this mission has huge promise."

Prof David Ehrenreich from the University of Geneva said quite a few early observations made with Cheops would be of "super-Earths".

"These are planets that are assumed to be rocky like Earth - but much bigger, more massive. And much hotter, too. Lava worlds," he explained.

55 Cancri-e fits into this category. More than eight times as massive as Earth, it takes just 18 hours to circle its parent star. Scientists believe it to have a global ocean of molten rock on its surface.

About 80% of observing time on Cheops is reserved for the project consortium. Led from the universities of Bern and Geneva, this team has members in eleven European nations (with Esa as a partner also). The other 20% of time is being offered to the community at large. And the first of these external proposals will be studied in coming days. Cheops will look at a burnt-out, or white dwarf, star to see if there is any planetary material moving around it.

Nobel Laureate Prof Didier Queloz, from the universities of Cambridge and Geneva, said the goal of Cheops was to improve our ideas for how planets were created.

He told the BBC: "We have built a whole theory of planet formation by observing only the eight planets of our Solar System, but by extending our observations to other kinds of planets that have no counterpart in our Solar System - we should be able to add the missing parts of this theory and get, let's say, a bigger perspective on how we actually fit in."

Science planning for Cheops is run out of the Geneva; the telescope itself is controlled from Spain, at the National Institute for Aerospace Technology in Torrejon on the outskirts of Madrid.

While the coronavirus crisis has meant considerable disruption for many space projects, Cheops has been largely unaffected.

"The completion of the test phase was only possible with the full commitment of all the participants, and because the mission has an operational control system that is largely automated, allowing commands to be sent and data to be received from home," said Prof Willy Benz from the University of Bern and principal investigator on the mission.

Cheops is a short form that stands for CHaracterising ExOPlanet Satellite.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos