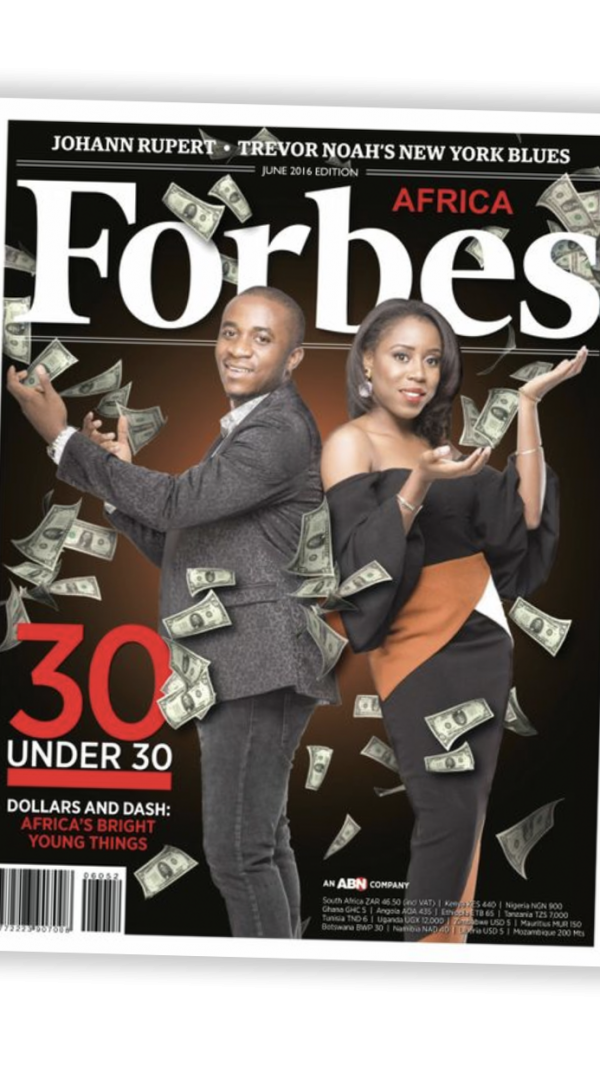

There he was, smiling on the cover of Forbes Africa magazine, dollar bills raining like confetti. It was June 2016, and Obinwanne Okeke, then 28, was on top of the world; he had just landed a coveted spot on the magazine’s prestigious 30 under 30 list of African entrepreneurs. In the article, he was one of many whiz kids described as “Africa’s bright young things.”

The 17th child of a polygamous father whose mother was the fourth wife, Okeke’s father died when he was 16, and his mother, a teacher, worked multiple jobs to put him and his siblings through school. Growing up in Ukpor, a village in southeastern Nigeria, was tough, and luxuries like sneakers or a Game Boy were hard to come by, he said in a 2018 BBC interview.

But he persevered, he said, studying in South Africa and Australia, earning a master’s degree in international relations and counter-terrorism at Monash University. He started his business in Nigeria in 2013. That business — which, as he has alluded to in other interviews, involved low-cost housing and green homes — expanded into South Africa, Botswana, and Zambia, with a potential addition in Uganda. His interests were worth almost $10 million, he said.

Okeke named his business Invictus, after the poem by William Ernest Henley about resilience in the face of adversity. It was said to be Nelson Mandela’s favorite poem.

“Invictus is in construction, agriculture, oil and gas, telecoms and real estate. He has 28 permanent and 100 part-time employees across nine companies,” Forbes Africa wrote in Okeke’s entry.

But that much-lauded business empire existed alongside Okeke’s criminal enterprises, the FBI later wrote in an August 2019 affidavit. Turns out, Okeke had been involved in a string of sophisticated online scams since at least 2015 — including when he was gracing that glossy Forbes Africa cover. He was arrested at Dulles International Airport, Virginia, on August 6, 2019, for defrauding a company of nearly $11 million. He pleaded guilty to conspiracy to commit wire fraud on June 18, 2020, and now faces up to 20 years in prison at his sentencing in October. Okeke’s rapid ascent as a supposedly successful entrepreneur — and his subsequent defenestration — reflects a growing trend in online scamming known as business email compromise (BEC).

The tale of the Nigerian online scammers stretches back to the 1990s, when cybercafes sprung up across the country as internet access became increasingly widespread. Young men popularly known as “Yahoo boys” became famous for conning their unsuspecting victims out of money by posing as romantic interests — typically American soldiers based in active conflict zones in the Middle East — or as wealthy royals in need of help getting a relative’s money out of some bureaucratic logjam. Their notoriety is now mainstream enough that they’ve become a pop-culture joke. In an episode from the second season of the TV show “Black-ish,” a concerned sibling chastised her brother about his potential love interest, convinced he was being duped by a scammer. “This is a middle-aged Nigerian man who wants your money or your kidney,” she told him. The youngest sibling added, “I’m trusting to a fault, and even I know this screams Nigerian scam.”

Okeke’s case reflects how much has changed since then. Rather than settling for petty romance schemes, some scammers are now targeting the email accounts of executives at Western companies, tricking their companies into sending wire transfers to supposed overseas suppliers who then fraudulently transfer those funds into the scammers’ bank accounts. The stakes involved in BECs are high in nearly every possible way: they target wealthy and prominent victims and use complex tools to defraud them, and if the plot succeeds, it results in a windfall. Whereas the targets of online romance scams are usually older Americans or other lonely Westerners desperate for affection (or the occasional naïf fooled into going into business with a seemingly sweet-talking African prince), email compromise focuses on businesses ranging from small-sized enterprises to multinational corporations. Scammers typically single out high-level executives, usually the CEO, CFO, or COO, “the real decision-makers who have the power to sign checks and grant approval,” Eniola Fadare, a Lagos-based computer security expert, told Rest of World. The goal, after gaining control of these decision-makers’ email accounts, is to authorize wire payments of money that will largely end up in accounts controlled by the scammers.

In contrast to romance scams, where the guys — and they’re almost always guys — find their marks on Facebook, Instagram, or any number of dating apps, email compromise is a “patient scam,” Fadare said, that involves quietly shadowing a company or its executives for months, to determine the types of businesses they’re involved in and the vendors who will need to be paid. The operational costs of pulling off one of these scams often add up to millions of naira, but the payoff can be worth it. While romance scammers may make off with anywhere from $350 to $3,000, BEC scammers can potentially rake in much more. Olalekan Jacob Ponle, who also went by the name Mr. Woodbery, was arrested on June 10, 2020, in Dubai for allegedly stealing $15.2 million in a scam targeting a Chicago-based company.

BEC involves a high degree of sophistication and collaboration between masterminds and co-conspirators, who provide services like designing fake landing pages for hijacking email accounts and harvesting passwords. There are also money mules who provide accounts, sometimes referred to as “houses,” to park the proceeds of the scams. A 24-year-old Lagos-based scammer, who spoke to Rest of World through an intermediary to preserve his anonymity, said that romance scams are “easier and cheaper to do” than BEC scams. But they’re not the sure bet they once were, because of how widespread they are. “People are getting educated and enlightened,” Fadare said.

Business-related scams involve individuals spread around the world, requiring authorities to cooperate across borders; Mr. Woodbery was extradited to the United States after being captured by Dubai police. Last year, 281 individuals, including 167 in Nigeria, were arrested for their involvement in BEC schemes as part of an international raid called Operation reWired. Arrests were also made in Turkey, Japan, Italy, and elsewhere. The cases are being tried across several jurisdictions in the U.S., because the victims are American.

In a statement from the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Central District of California on the arrest of Hushpuppi, a flamboyant Instagram celebrity with 2.5 million followers, U.S. Attorney Nick Hanna described BEC as “one of the most difficult cybercrimes we encounter, as they typically involve a coordinated group of con artists scattered around the world who have experience with computer hacking and exploiting the international financial system.” Paul Delacourt, the assistant director in charge of the FBI’s Los Angeles Field Office, claimed that the FBI recorded $1.7 billion lost to BEC schemes in 2019.

The crime that got Okeke arrested began on April 1, 2018, making it perhaps the most lucrative prank ever pulled on April Fool’s Day. The victim was Unatrac Holding Ltd., the export sales office of a dealer for Caterpillar, a heavy industrial and farm equipment company. The company is based in Slough, a town about 45 minutes outside of London. According to the FBI statement, Unatrac’s CFO received an email containing a login link for his Microsoft Office 365 account and entered his login details, believing it to be real. Instead, it was a spoof website crafted by Okeke and unnamed associates to gain access to the CFO’s email.

After they did, the hackers sent invoices from an email address intended to mimic that of a legitimate vendor to the CFO’s email, using invoice templates and logos found within the compromised account to lend an air of legitimacy to the documents. Minutes later, those fake invoices were forwarded to Unatrac’s finance team from the CFO’s email. Because the finance staff had no reason to doubt the provenance of the wire transfer requests, they processed about 15 payments between April 11 and April 19, 2018. The company that allegedly submitted the invoices, Pak Fei Trade Ltd., was sent at least three payments that totaled more than $3 million, with the payments going to overseas accounts. In total, almost $11 million was stolen from Unatrac.

About the same time the scam was underway, Okeke was an invited speaker at the London School of Economics’ Africa Summit, alongside luminaries like Ghanaian President Nana Akufo-Addo and many other prominent African businesspeople. He also partook in that BBC interview, telling tales of growing up poor and how he was introducing low-income housing to a Nigerian property market saturated with expensive homes.

By the time the company realized it had been hoodwinked, it was too late to cancel the transactions, and little of the funds were recovered, according to the FBI statement. To avoid detection, the hackers set up email filters that immediately intercepted legitimate emails to and from the CFO, marked them as read, and moved them to another folder outside the inbox.

Fadare, the security expert, explained that, in conjunction with setting up email filters, scammers do not work “at active hours when they know the CEO is awake or busy.”

Additionally, “they clear the emails from the boxes as soon as they’re received. The real CEO, when he logs into his email, is not going to see anything,” he added. Fadare said scammers bank on people not carefully scrutinizing messages they believe come from a trusted source. “They prey on people not being curious enough to check.”

“CEOs assume, because they pay millions of dollars for security and their staff is being trained, they don’t have to take precautions themselves,” Fadare told Rest of World. “That’s why they’re the ones [scammers] aim for. They’re not going to go for the intern whose life is at risk if he messes up; they won’t go for that guy, because the intern takes everything seriously.”

Unatrac contacted the FBI in June 2018, and a case was opened the following month.

“CEOs assume, because they pay millions of dollars for security and their staff is being trained, they don’t have to take precautions themselves.”

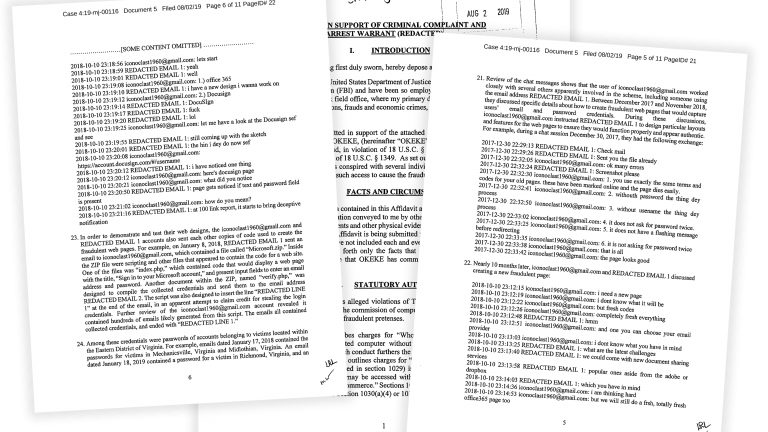

The task of identifying Unatrac’s intruder began in earnest. First, the FBI noticed that a rogue email address, iconoclast1960@gmail.com, had been sent a file downloaded from the CFO’s OneDrive account. A query on Whois, a widely used protocol for searching databases of internet registration domains, showed that the email had been used to register several websites for phishing purposes. One of the fake websites was designed to mimic the original domain of a United Arab Emirates–based company that “could logically have business relationships with Unatrac,” the FBI wrote in the complaint.

Through a federal search warrant, authorities received information about iconoclast1960@gmail.com from Google. It detailed various fraudulent schemes the account was used for, ranging from computer intrusions to chats with co-conspirators on how to create spoof websites to obtain email passwords. The FBI said it found more than 600 email passwords and copies of passports and driver’s licenses. They also found messages about wire transfers from Unatrac as well as evidence of an earlier victim: Red Wing Shoes in Minnesota was defrauded of $108,470.55 in January 2018, months before the Unatrac loot. The Unatrac CFO’s email account was also found to have been accessed at least 464 times, mostly from IP addresses in Nigeria, during the intrusion. Okeke was based in Abuja, the capital.

The records from Google were a treasure trove. The recovery email for the rogue account for the “iconoclast” email was alibabaobi@gmail.com, with several accounts linked by login session cookies. (Google’s cookies record all Google accounts accessed on a particular device using the same web browser, indicating they are likely used by the same person.) One of the linked accounts, they found, was referenced as a contact email on Nairaland, a popular Reddit-style forum in Nigeria. That Nairaland account listed the Twitter handle @invictusobi, which belonged to Okeke. The Twitter account also pointed to an Instagram page.

As an image-conscious entrepreneur, Okeke was an ardent Instagram user, frequently chronicling his jaunts across the world. That would contribute to his undoing. On three occasions, Google’s IP logs showed that the user behind iconoclast1960@gmail.com had logged into the account from Seychelles, London, and Washington, D.C. On all relevant dates, pictures posted on Okeke’s public Instagram put him in the same countries. Further checks proved equally damning, as a search for “invictusobi” in the iconoclast1960@gmail.com account turned up a crucial piece of evidence: on March 1, 2016, a picture of a white bathtub next to wooden doors with glass panes was emailed to invictusobi@icloud.com. That day, Okeke posted the same photo on Instagram, suggesting that he was indeed behind the email account involved in the Unatrac fraud. The FBI swiftly arrested Okeke on the same day he was supposed to return to Nigeria from a routine trip to the U.S.

For 13 months, the U.S. government investigated and built its case against Okeke, who apparently had no inkling he was under any suspicion up until his arrest. The case became a cause célèbre in Nigeria, with many wondering how a respected entrepreneur became entangled in a web of deceit. For some, it was a warning to young people that not all that glitters is gold.

Okeke’s arrest shattered his narrative as an odds-defying, high-flying entrepreneur. While he was in the spotlight, he carefully crafted a persona as a hardworking young man, and many were surprised to learn he was not who he presented himself to be. With the lavish-spending con men of Instagram, it wasn’t a huge leap to suspect they were involved in fraudulent schemes. But who could possibly think a smooth-talking and highly educated entrepreneur was too? Okeke was carrying out two scams in one go: the Unatrac fraud that got him arrested and the high-wire act of image laundering with compelling stories that convinced society he was the real deal and made respectable outlets like the BBC and Forbes sing his praise.

It is unclear why Okeke, who initially pleaded not guilty, backed down and admitted to the crimes. In his plea agreement, he waived his right to appeal and agreed to forfeit “all interests in any fraud-related assets.” His attorney did not respond to requests for comment from Rest of World.

Nigeria has always had a fraught relationship with its online scammers. A lot of people say they tarnish the country’s global image and are one of the reasons Nigerians face increased scrutiny during visa applications. A number of payment platforms, including PayPal, are unavailable in Nigeria or offer limited access to Nigerians. Fraudsters also provide cheap fodder for the “Nigerian scammer” narrative. A recent FBI tweet asking for the public’s help finding suspects wanted for scams read, “Help the #FBI find six Nigerian nationals wanted for their involvement in business email compromise (BEC) schemes resulting in $6 million in losses.” But the tweet links to a list of “Cyber’s Most Wanted,” which named 80 groups and individuals from at least 12 countries, including Sweden, Latvia, and Romania.

Yahoo boys insist that poverty and a lack of opportunities leave them no choice but to turn to the dark side. Their supporters contend they’re simply taking from the haves and giving to the have-nots, a digital form of reparations for the sins of slavery and colonialism. Some see them as hustlers, modern-day Robin Hoods who stimulate the local economy. After all, according to Forbes Africa, Okeke had 128 employees in 2016, each with their own families and personal obligations. And although people acknowledge the scammers are committing crimes, they argue they’re not so different from politicians who embezzle public funds.

“Best thing is to make small money from it as fast as possible, look for a way to invest, and stop. No one expects to scam forever.”

The scammer who spoke to Rest of World says he sees it as a means of subsistence. “I’m just trying to eat and feed my family,” he, an economics graduate, said. He hasn’t had a job, he told Rest of World, since graduating from university in 2016 with an economics degree. Of Nigeria’s estimated 180 million people, 23% were unemployed in 2018, with those numbers expected to rise by the end of the year, due to the pandemic.

Asked if he has any fears of being arrested, especially in light of recent U.S. crackdowns, he said, “There are risks, but there are also ways to be careful; besides, small amounts of money aren’t usually traced unless the client actually goes to report.” (Yahoo boys refer to their marks as “clients.”)

He’s been in the business since 2016 but has plans to leave the trade: “Best thing is to make small money from it as fast as possible, look for a way to invest, and stop. No one expects to scam forever.” He didn’t say how much he’s earned through scamming in the past four years, but said that he’s hoping to get “[a] couple millions more.”

If scammers are vilified in American culture, they’re welcome with open arms in certain corners of Nigerian society, including parts of the music business. Musicians regularly release songs praising people suspected of being involved in various criminal schemes. Segun Akande, a content and design strategist at a record label, told Rest of World that Nigerian music and shady characters have always had a cozy relationship. This dates back to at least the late 1960s and down through “the cocaine pushers of Fuji music, the 419 boys of early Afrobeat,” he said. “Musicians have struck mutually beneficial relationships with loose money.”

In the BBC interview, Okeke took exception to Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari’s characterization of Nigerian youth as lazy, saying he was “offended” by the comments. That interview aired on April 26, 2018, just one week after he’d successfully defrauded Unatrac — all while moonlighting as an upstanding entrepreneur. “I try so much to operate in a country that has no enabling environment for small businesses,” Okeke said in the interview. “I definitely am not a lazy youth.”