2 Big NASA Space Missions Ended This Week, But Don't Panic

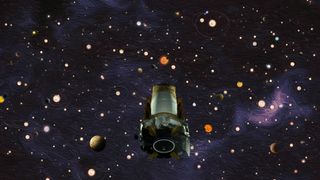

It's easy for a superstitious mind to jump to anxious conclusions from this week, after NASA announced the end of two long-running missions: the exoplanet-hunting Kepler space telescope and the Dawn mission that visited the asteroid belt.

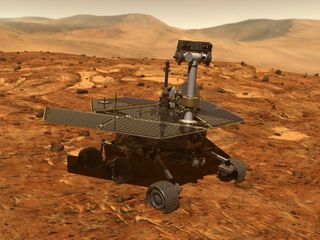

And those high-profile finales come in the midst of a spree of other spacecraft troubles: the Opportunity rover on Mars remains silent nearly five months after a planet-engulfing dust storm, and the Hubble Space Telescope and Chandra X-Ray Observatory were both briefly offline in October.

But as NASA personnel stressed during a news conference Tuesday (Oct. 30) to announce the end of the Kepler mission, the sudden spurt of bad news is no reason to panic. "We always try to get as much science as we can out of our spacecraft," Paul Hertz, NASA's head of astrophysics in the Science Mission Directorate, said during the news conference, adding that the agency has more than 60 science spacecraft at work right now. [Gallery: A World of Kepler Planets]

"If you only pick out the ones that are getting toward the end of their life then you can make a story, but if you look at the entire portfolio of spacecraft, I don't think we have a problem at all, I think we are in a golden age of NASA science," Hertz said.

Both the Kepler telescope, which identified more than 2,600 alien planets, and the Dawn spacecraft, which visited the asteroid Vesta and the dwarf planet Ceres, ended because they no longer had enough gas in the tank. Engineers on both missions knew their ends were looming, since they could calculate remaining fuel estimates.

Both spacecraft used chemical fuel to twist themselves back toward Earth and beam their findings home; without that fuel there was no way to learn from our distant emissaries. Sure, each mission could theoretically have been stocked with more fuel, but not without fattening their price tags. And both missions lasted far longer than they were initially designed to endure, overcoming serious mechanical problems along the way.

When the Kepler mission began in April 2009, it was originally designed to last three years — instead, it lasted until 2013, when two broken reaction wheels forced its original mission to end. The telescope's engineers still didn't abandon it; instead, they reprogrammed it, so that rather than look for exoplanets in one particular patch of the sky, it hopped from region to region. Reincarnated, the telescope completed another four years of observations.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Dawn also survived reaction-wheel failures that threatened to sideline the spacecraft at the end of its stay at the asteroid Vesta. In Dawn's case, engineers rescued it by using fuel to make small adjustments to its position. This spacecraft also blew past its original timeline, spending 14 months at Vesta instead of the scheduled seven and more than three years at the dwarf planet Ceres instead of the scheduled five months.

Although the fate of the Opportunity rover remains unknown as NASA continues to try to revive it through January, the rover has outpaced its goals just as dramatically as its spacefaring cohorts. Its mission was originally scheduled to last just 90 Martian days, each about 40 minutes longer than a terrestrial one. Instead, the rover has puttered the Red Planet for more than 14 years. [10 Years on Mars: Smithsonian Celebrates Spirit, Opportunity Rovers (Photos)]

(Opportunity's cross-planetary companion, the Curiosity rover, also ran into a small hiccup in its work when a bug knocked its active computer offline. Engineers successfully triggered the robot to switch to its identical second "brain.")

As for the last contenders for fallen spacecraft this fall, both the Hubble Space Telescope and the Chandra X-Ray Observatory issues were never expected to be fatal injuries. In both cases, engineers knew the scientific instruments were unharmed, and that the troubles were likely caused by the telescopes' gyroscopes, which control how the instruments orient themselves in space.

Beyond the casualty list, NASA also has some beginnings worth remembering. Its Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, or TESS, picked up where Kepler left off, beginning observations in late July, and has already identified multiple possible planets. The Parker Solar Probe mission to "touch the sun" launched in August and is making its first close approach to our star this week.

NASA's new Mars lander, called InSight, will touch down just after Thanksgiving, ready to study the Red Planet's interior, and the New Horizons spacecraft will ring in the new year by swinging past a distant Kuiper Belt object.

So buckle your seat belt — this ride isn't over.

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us @Spacedotcom and Facebook. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.