From Apollo to Artemis — How Astronaut Food May Change When We Return to the Moon

Future astronauts might eat very old food and fresh vegetables.

Apollo astronauts had to deal with questionable flavors and lackluster options while dining in space. When humans return to the moon with NASA's Artemis program, the menu might be very different, including packaged foods that are many years old alongside fresh fruits and vegetables.

In the earliest days of spaceflight, trips were so short that food was almost an afterthought: "The first food was basically tubes and cubes," Michele Perchonok, a food scientist who previously worked at NASA as the HRP advanced food technology project manager and the shuttle food system manager, told Space.com.

But, as the Apollo astronauts began to spend more than just a few hours in space, NASA had to re-think what they should eat and how it should be made and packaged. Astronauts with Mercury and Gemini had issues maintaining body weight and overall health, and so dietary changes were essential to the program.

Related: Space Food Photos: What Astronauts Eat in Orbit

Apollo astronaut food had to be lightweight, quick to prepare, well contained, nutritious, calorific enough to maintain crew weight, and it couldn't pose a threat to crew health, as there were concerns that astronauts eating in zero gravity might choke on their food.

Astronauts on the Apollo missions were the first to have hot water, which improved taste (though the astronauts would likely testify that it still wasn't great) and expanded menu options by making rehydration easier. The Apollo astronauts also tested the then-new "spoon bowl," a plastic bowl that could hold food, which could then be eaten with a spoon (a revolutionary space food technology at the time).

Before each Apollo launch, the crewmembers and their backups selected their preferred food items from the roughly 70 available menu items that could be packaged and sent to space. These items were then organized into balanced meals and scheduled for the duration of each mission. For the Apollo astronauts, breakfast might include applesauce, a breakfast drink, sausage patties and cinnamon bread cubes; lunch might include chicken sandwiches, coconut cubes, sugar cookie cubes and cocoa; and dinner might include spaghetti with meat sauce, cheese sandwiches, banana pudding, pineapple fruitcake and a grapefruit drink.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

From Gemini onward, NASA astronauts have also had the option of selecting shrimp cocktail, and it has remained a favorite among them throughout the years. Easy to freeze-dry, shrimp allegedly tastes about the same in space as it does on Earth. Astronauts have also reported dulled taste buds and nasal congestion in space, making spicier additions like cocktail sauce hit items.

Chocolate also continues to be a favorite among astronauts. "The crewman has to be very careful about adjusting to a lack of gravity sensation. We had very small shrimp that had a little bit of cocktail sauce, and when exposed to water, were very, very tasty," Apollo 11 astronaut Buzz Aldrin said in a Reddit AMA.

Apollo 11 astronaut Michael Collins also notably enjoyed hot coffee in space as he orbited the moon. "Behind the Moon, I was by myself — all alone but not lonesome," Collins said in a Google video celebrating the 50th anniversary of the mission. "I felt very comfortable back there; I even had hot coffee," he said.

Advancing astronaut meals

Astronaut food has evolved tremendously over the years, but food scientists at NASA today still work to overcome the same core obstacles that the team developing the menu for Apollo grappled with. However, while many challenges remain the same, advances in technology and lessons learned throughout the history of human spaceflight have led to food with improved taste as well as an increase in options.

Today, any bread that once made its way into space has been replaced by tortillas, which do not create crumbs and can be made to last for over a year without going bad. Food sent into space today also has to last longer as mission durations have increased. The International Space Station is home to astronauts from all over the world and their favorite dishes from home. Astronauts today enjoy a variety of foods, such as teriyaki beef, cashew curry chicken, and macaroni and cheese.

Future space cuisine

But how will space food change as NASA plans to return to the moon with the Artemis program and to Mars, aided by the efforts of space agencies and commercial space companies? Will astronauts on these longer-duration missions require different types of food, or will their meals require special preparation? According to Perchonok, the most important factors in the kinds of space food available in the future will be the need to maintain the food's nutritional quality while ensuring its shelf life.

"Current ISS food system shelf life is 12 to 18 months," she explained. "On a Mars mission, jumping ahead, there will be no resupply missions. That's why the shelf life of the packaged food has to be somewhere in the order of five years, maybe even seven years."

Scientists have to make foods that will not only remain safe to eat but also will retain adequate nutrition, as vitamins and minerals degrade with time, Perchonok noted. She added that vitamin supplements do not solve this issue. "Just taking a vitamin pill, they are even less stable over time than [vitamins in] the food," she said.

Scientists working to prepare food for long-term missions to the moon and Mars will also have to factor in how radiation might affect food longevity and nutrition, Perchonok said. Future astronauts on the moon and Mars will be up against much higher rates of radiation than astronauts aboard the space station, and this could potentially even affect the food they eat.

Food scientists will also have to consider gravity when preparing foods for these missions, since the differences in gravity on Earth, the moon and Mars might change the ways that fluids move in foods and might influence NASA's food-preparation options.

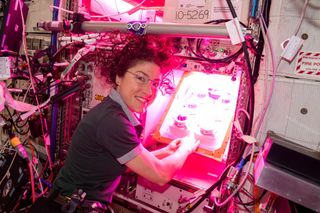

Experiments aboard the space station have shown that it's possible to grow fruits and vegetables in space, but it will take a long time before space-grown food could make up a significant portion of an astronaut's diet, Perchonok said. However, with time, and if and when a base on Mars or the moon is built, Perchonok said that she could definitely foresee astronauts using larger-scale growth chambers (larger than those used in experiments on the space station) to grow fruits and veggies to pick and eat.

So, while future space food might have to be specially prepared and packaged to last for years, astronauts on the moon and Mars might have the added bonus of fresh fruits and vegetables.

- Mercury and Gemini Food (1961 to1966

- This NASA Experiment Shows Promise for Farm-Fresh Foods in Space

- How Urine Could Help Astronauts Grow Food in Space

Follow Chelsea Gohd on Twitter @chelsea_gohd. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Chelsea “Foxanne” Gohd joined Space.com in 2018 and is now a Senior Writer, writing about everything from climate change to planetary science and human spaceflight in both articles and on-camera in videos. With a degree in Public Health and biological sciences, Chelsea has written and worked for institutions including the American Museum of Natural History, Scientific American, Discover Magazine Blog, Astronomy Magazine and Live Science. When not writing, editing or filming something space-y, Chelsea "Foxanne" Gohd is writing music and performing as Foxanne, even launching a song to space in 2021 with Inspiration4. You can follow her on Twitter @chelsea_gohd and @foxannemusic.