Three hours in uncanny valley

Who framed Ryoma Echizen?

The key to a solid high five is knowing where your buddy's hand is and when to stop swinging.

Celebrated manga artist Konomi Takeshi did not have this knowledge.

At least, he didn't appear to from where I was sitting. The move probably looked fine from the middle of the ground floor of the Pacifico Yokohama National Convention Hall, where the seats were nearly level with the stage. Up on the third floor, seated slightly left of center stage, I saw his hand bypass Tōyama Kintarō's entirely.

The fact that Kintarō was a virtual-reality character may have had something to do with that.

I've been a fan of the Prince of Tennis (for short, Tenipuri) franchise since I was a clumsy high schooler whose friends coaxed her onto the hard courts at our SoCal high school. We'd put in a few hours swatting the ball back and forth, then go to someone's house and make wheatgrass-and-ice-cream smoothies while we watched bootleg VCDs of the latest episodes purchased from the uncle at the 99 Ranch Market, the only Asian grocery store in town. The manga, by author and artist Konomi, was first serialized in Shōnen Jump in 1999; the anime premiered in 2001, though I didn't find it until the first run had nearly ended.

The story begins with Echizen Ryōma, a 12-year-old tennis prodigy returning to Japan to enroll in the same middle school his former sports-star father attended after years living abroad in America. Once he joins the Seishun Gakuen tennis club, the standard narrative beats of sports anime proceed like clockwork: dramatic showdowns, traumatic injuries and the quest to take the team to the national championships. The show's real hook is the characters. With eight-player teams coming from all over Japan, there's a diverse enough cast that nearly anyone can find a character to cheer for.

There have been OVA specials, full-length movies, musical adaptations, Taiwanese and Chinese TV dramas, and a mobile rhythm game. With its plethora of roles, Tenipuri also has an abundance of character songs -- more than 300 of them, in fact. And of course there are concerts, the most spectacular of which are large-scale productions called "Festas."

Going to a Tenipuri Festa has been on my bucket list ever since I saw rips of the 2011 Festa on YouTube. Every few years, a few dozen of Tenipuri's voice actors dress up in their characters' team jerseys and take turns singing and dancing for three hours in sport and concert arenas like the Budokan or Ariake Coliseum. The fun of Festa is the gap between fiction and reality. The voice actors are in character as they interact with each other, but the lack of physical similarity to the middle school boys they portray (the majority of the voice actors are men between the ages of 30 and 50) allows them to dance or perform gags that would be otherwise unsuited to the characters' personalities. Two teenage boys who take themselves very seriously would never reenact the choreography for WINK's 1980s hit "Lonely Tropical Fish." Two men in their 40s could grin their way through it. The franchise inspires remarkable devotion from its actors, some of whom write lyrics and compose music for their own character's songs. Even the manga artist joins in on the fun. Konomi -- playing himself -- composes and performs his own music, interacting directly with his characters as they sing and dance together. (The fourth wall is made of Kleenex in this franchise.)

This year's Festa was going to follow a slightly different pattern. Konomi called it "Perfect LIVE ~One-Man All-Tenipuri Festa 2018," announcing via livestream on the instant messaging platform LINE that he would perform with VR renderings of his characters, rather than live voice actors.

While the term VR seems to imply immersive headset experiences in the Vive or Oculus Rift, it's sometimes used as a marketing term in Japan to refer to holographic performances where digital characters appear on-screen. A Hatsune Miku concert might be called VR, as are some 3D movies.

This sounded vaguely suspect, but it was the first time I'd managed to be in Japan when Festa tickets went on sale. Of course I was going to go. Having missed the initial pre-reserve lottery, I shuffled to a 7-Eleven ticket kiosk at midnight to make sure I got a seat. And when the fateful day finally rolled around, I dug my old Seigaku team jersey out of storage, gave it a good hit of Febreze, and hopped on the Fukutoshin line to Pacifico Yokohama National Convention Hall.

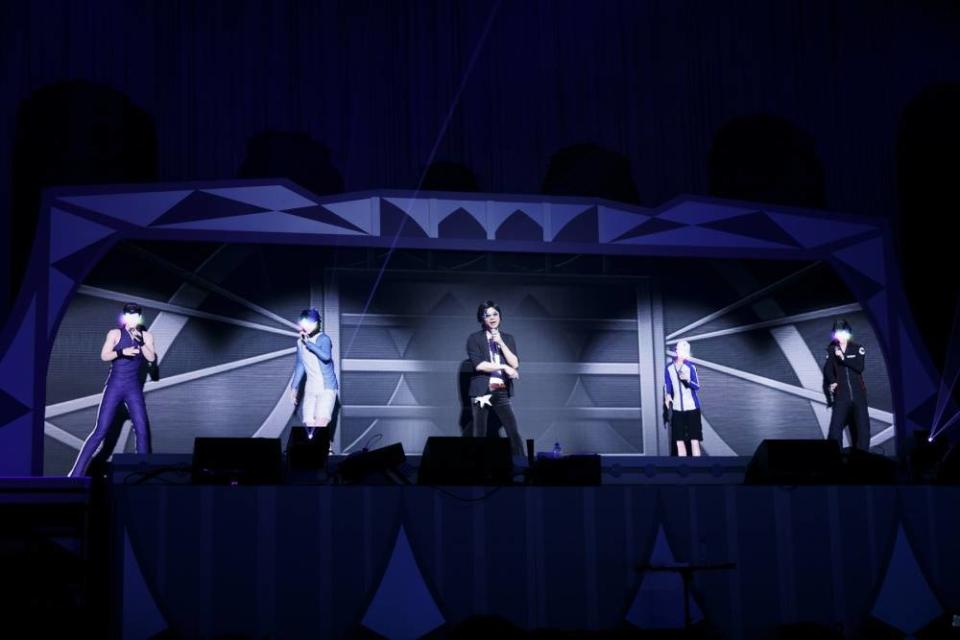

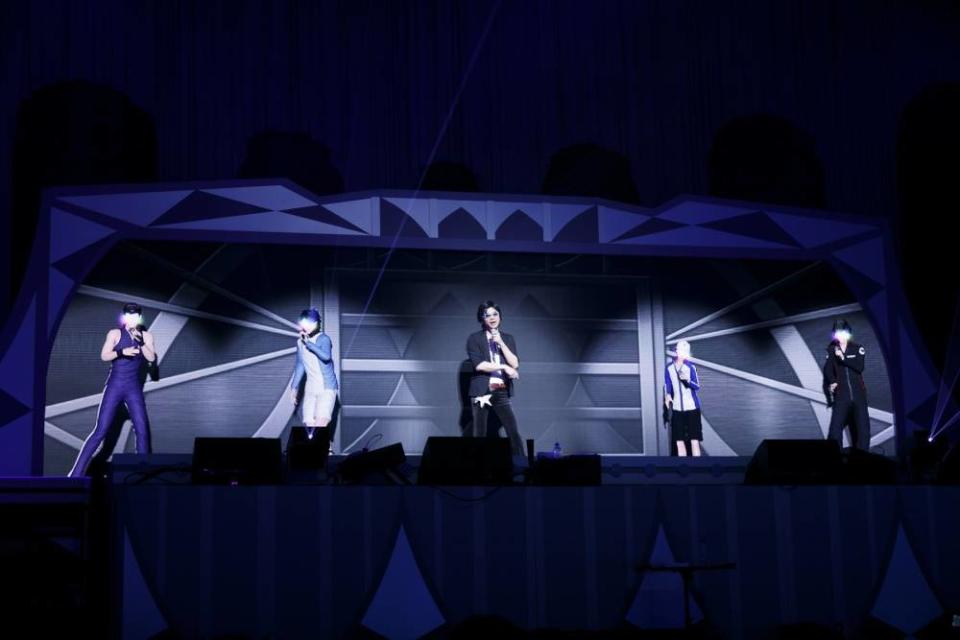

Built up rather than out, the hall is both compact and cavernous at the same time. It boasts 5,000 seats, the majority of which are on the ground floor. I had not managed to secure one of those seats. Instead, I was on the third-floor balcony, looking down on a two-tiered stage with three screens: one along the back of the stage's upper level, with a smaller one on each side zoomed in on the performers' facial expressions.

The moment Konomi fired himself up from under the stage's upper tier floor (a favorite move that he'd used during past Festa appearances), I was pumped. He sang Hiro-x's "Future," the original opening theme for the anime, and the whole crowd was happy to sing along to the chorus.

Each character here was their actual height, with careful attention paid to proportions and the physical proximity of characters who had interpersonal histories.

When the VR characters started filling in the big screen behind him, I was less pumped. In previous Festas, the voice actors had run across the stage to greet different seating sections, jumped down to high five the audience members and danced along the staircases between the upper and lower levels. This time, confined to their digital prison, the boys could not utilize the full stage -- I was probably just imagining the jealousy in their eyes as Konomi sat down on a staircase to watch them sing.

Unlike Hatsune Miku concerts, where the virtual model is projected in larger-than-life size, each character here was their actual height, with careful attention paid to proportions and the physical proximity of characters who had interpersonal histories. Although the characters' shadows had been rendered, the digital models lacked a certain depth. They could jump up or move side to side but they could not step closer to or away from the audience, giving them a disconcerting flatness.

At least part of the problem was the hall design itself. It predated VR technology, so obviously it couldn't be optimized for its use. Things that might have looked fine straight-on failed when viewed at an angle. Konomi's attempts to interact physically with the onscreen characters appeared clumsy from my perspective. His pantomimed high fives reached too far, landing on the characters' wrists instead of their palms. Pats on the shoulder looked like pats on the air two inches above it. While VR technology can theoretically bring 2D media to live shows or allow artists to collaborate despite packed schedules, it's still a novelty. VR has to work viewed from every angle, not just the most expensive seats in the house.

The VR Festa was supposed to collapse the gap between fiction and reality by bringing our beloved characters to life. However, I found that the virtual renderings actually called uncomfortable attention to that gap.

Konomi had previously bantered with the human voice actors, but his tone shifted considerably when he interacted with the VR characters. Rather than treating them as friends closer to his own age, he took a more paternal attitude to his ragtag troop of 14-year-olds, reassuring them that they would grow up to be stronger than they are now.

Most of the character interactions were pre-recorded, with a hidden sound engineer triggering the dialogue behind the scenes. The downside of this approach is that the VR Festa is much more tightly scripted than an entirely human show. Without immediate access to the voice actors, there's no room for improvisation. This presented a slight issue during the performance.

"You seem livelier than you used to be," VR Fuji said to his former team captain Tezuka.

"Is that so," VR Tezuka replied very politely. "Thank you very much."

A whisper ran through the crowd. Why had Tezuka suddenly switched from plain language to formal? Given that Tezuka/Fuji is a fan favorite pairing, this abrupt tone shift sounded like a distancing move or a brewing quarrel.

"How about you sing a duet with Fuji?" Konomi broke in.

"Is that so," Tezuka repeated. "Thank you very much."

Somehow, the scripted lines had gotten out of order; whatever VR Tezuka had been programmed to say had been lost, and the prerecorded Fuji couldn't brush past the mistake with a joke like a live actor would. When I checked the concert hashtag after the show, it was full of speculation about what the missing line could have been.

Somehow, the scripted lines had gotten out of order.

The audience was shocked when the crew took microphones down on the floor so that the virtual Yukimura Seiichi could talk to us. At first I suspected the girls were plants, intended to add a stronger sense of reality to the experience. One girl, when confronted with the microphone, seemed to worry that she was dealing with pre-recorded lines. "Is it really okay for me to say my name?" she asked the mic operator. "It's an uncommon one." But Yukimura repeated her name back to her, told her she had a good look in her eyes, and asked if she'd like to join his tennis club. Overcome with joy, she teared up. Her favorite character had stepped into the real world for just a moment, and he'd been kind to her. During the encore it was revealed that Nagai Sachiko, Yukimura's voice actor, had been backstage the entire time, and that the audience interactions had been a live broadcast.

However, some scripted moments didn't quite land for me. When the VR characters thanked their author for taking care of them for the last 19 years, I almost felt as if I was intruding on a private moment. Coming from human voice actors, these moments seem sincere, because the author truly has been influential in their work. From the mouths of models these words seemed hollow. I couldn't ignore the fact that Konomi himself had put those words in their mouths.

VR characters, unconstrained by things like bad backs and tricky hips and that pesky gravity thing, are able to do some things that voice actors can't. Sugimoto Yū, the voice actor behind Tōyama Kintarō, is incredibly talented, but she's 43 years old and probably not capable of the backflips and cartwheels that Kintarō indulges in. However, while the choreography was great on a technical level, it also led to some jarringly out-of-character moments. Tezuka Kunimitsu, the former captain of the Seigaku team, lives and breathes tennis. I don't know when he could possibly have had time to take several months of hip-hop dance classes on the side. Meanwhile, although we know from previous concerts that voice actor Hosoya Yoshimasa can dance very well, his character Shiraishi hardly danced at all.

What most stood out to me was the lack of physical contact between characters, which set a mood entirely different from the live performances. Even though most of the voice actors don't look remotely like the characters they play, they're believable because of how they treat each other. The horseplay, the hugs, the punches on the shoulder: All their casual physicality embodied the deep bonds between their characters and spoke to a real-life camaraderie forged in the recording booth. The sense of affection between them was palpable even on video.

In contrast, the VR characters felt like the dolls they were. They were saying all the right things, in the right voices, but the banter didn't land for me without the body language backing it up. The characters walked past each other on the screen, but rarely touched. The only notable instance of physical contact was when Kintarō, during a banter segment, shoved his team captain Shiraishi -- standard teen jock horseplay. His simple push revealed why the characters couldn't touch each other. Generally, when you press on a butt, it indents. Shiraishi's body had no "give" to it; he stumbled, but his body itself seemed to have no real resistance against the pressure of touch. While the characters had idling animations to keep them fidgeting during conversation, their pops and locks were uncanny. When they held a pose mid-dance their chests were perfectly still. They weren't breathing. They didn't need to.

This was not "the Festa I'd waited for every day." This was a Who Framed Roger Rabbit? live stage show.

There was another significant advantage to bringing the real, mostly middle-aged voice actors out on stage: It let us ignore the age gap between ourselves and the characters.

Time moves a lot slower in fiction than in real life. I started reading the Prince of Tennis when I was 16. Now I am 29, while most of the characters have not aged more than a year.

This would be easier to deal with if the official merchandise didn't encourage us to view the characters as crush-worthy. There are two dating sims on Nintendo DS. There's character-specific rings and lockets. There are pillows depicting the boys in their pajamas. There are sexy disheveled boy blankets. There's even a wall sticker you can put up next to your bed so that you can wake up next to your favorite boy.

Your favorite 14-year-old boy.

Seeing the characters digitally rendered drives home their eternal youth. These Lost Boys are never going to grow up, but when we see the voice actors onstage, we can split the difference. Plenty of fans still have a 10-year age gap with the voice actors, but at least they're all adults.

The fourth wall incurred further shelling when the cast of the current run of Tenipuri musicals took the stage. Now, the characters were displaying a more human physicality with each other and with Konomi, moving across both tiers of the stage, knocking into each other playfully and pulling faces. However, the sudden, significant difference in the characters' voices lent the moment a sense of surreality. A Ryōma was singing, but not the same Ryōma who had been on stage a few minutes before, and definitely not the one I was used to. Katō Kazuki, who previously portrayed Atobe Keigo in the musicals, took the stage to sing a duet with the virtual Atobe.

Although we all clapped and cheered for the VR models, the crowd seemed less enthusiastic than they had in previously released Festa footage. I attribute this mainly to our collective uncertainty about how tight the timing was on the recorded dialogue -- if we cheered for too long, we might miss something. The encore made considerably less use of VR than the main show, bringing back the earlier live guests plus Nagai Sachiko, and seemed to garner much more audience engagement as a result.

The "VR Live" had been sold to us as a way to bring our favorite characters to life, but all the holograms had instead made me feel alienated.

After the show ended and I'd shuffled back out into the rain, I found myself drifting towards the train station with a strange sense of disorientation. When you spend a long time invested in some piece of media, you begin to think you know it. I'd seen enough footage of previous Festas that Nagai Sachiko and Konomi Takeshi had been what I'd expected. But every other character I'd seen had been slightly off in some way or another -- the wrong moves, the wrong reactions. I felt like all the characters I knew had been replaced with changelings.

The "VR Live" had been sold to us as a way to bring our favorite characters to life, but all the holograms had instead made me feel alienated. They lacked the warmth that the actors had brought to the low-tech stage show. In Japan, it's considered socially acceptable for teenagers to be fairly handsy with their friends, especially within school clubs; the voice actors had brought this body language from the screen to the stage. I hadn't realized how much of my emotional investment in the characters was in how they related to each other until I saw their 3D dolls breezing past each other like strangers.

Don't get me wrong, I'm probably going to do this again. But I'll wait until they work out a convincing high five first.