It was as a direct result of a newspaper article by the former Labour MP Joe Ashton, who has died aged 86, that a compulsory register of MPs’ financial interests outside Westminster was first established by the House of Commons in 1974. Ashton had called for the creation of such a register in a column he wrote for the party newspaper, Labour Weekly, under the heading MPs for Hire, and two weeks after its publication the newly elected Labour government took the first steps to seek to control political corruption.

The February 1974 general election had been held in the middle of a scandal involving the builder John Poulson, a man with many political contacts who had been imprisoned for using bribery to win lucrative public sector contracts. Labour had campaigned on a manifesto promising a compulsory register that might prevent a repeat, and Ashton had been prompted to write his article in April 1974 by a report in the Guardian suggesting that the new prime minister, Harold Wilson, was preparing to resile from that commitment in favour of a regime of voluntary declarations of interest.

Ashton was subsequently found (by a formal inquiry of the Commons’ Committee of Privileges) to have committed a serious contempt of parliament for suggesting, in his article, that MPs were available for hire. He was obliged to apologise for being what he himself called “a brave, mad whistleblower”, yet it was because of the political uproar his column caused that Wilson was obliged to act so swiftly after his general election win.

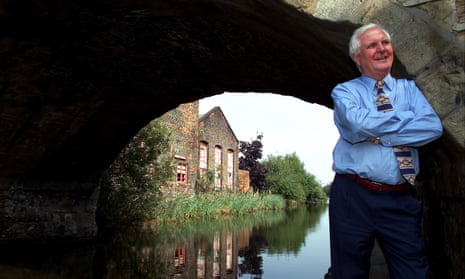

Ashton was a Yorkshireman who had a background of poverty and an instinctive populist sense of what mattered to his working-class constituents and to the Labour electorate. He was blessed with articulacy, had the ability to turn a colourful phrase and possessed a common touch – all attributes that took him into parliament and made him a punchy, popular newspaper columnist. He was an immensely active constituency MP for 33 years, but failed to progress at Westminster because of a lack of judgment that sometimes antagonised his parliamentary colleagues. He was also part of the unlucky generation of Labour MPs whose prime years at Westminster coincided with 18 years of uninterrupted Conservative government.

Born in the slums of Attercliffe in Sheffield to teenage parents, Arthur (known as Ike) Ashton and Nellie (nee Maloney), Joe was named after an uncle who had been killed at the age of four by a runaway steamroller. His father was intermittently unemployed, although he did stand-in shifts at the local Nunnery pit and later found work in the city’s steel industry. His mother was a “buffer girl”, polishing nickel-plated silver cutlery. Joe passed the 11-plus to attend High Storrs grammar school, but never wore the uniform his family could not afford, something his parents were successfully advised to blame on the lack of clothing coupons under wartime rationing. At 16 he became an engineering apprentice at Rotherham Technical College and joined the Labour party.

In 1954 he did two years’ national service in the RAF, taking part in the ill-fated Suez invasion before returning to a white-collar job as a design engineer, a post he held until narrowly winning a difficult byelection in Bassetlaw in 1968. The constituency, situated in the Nottinghamshire coalfield, was at the time facing pit closures imposed by an unpopular Labour government, and Ashton’s majority was reduced to 1.72%. A traditionally safe Labour “red wall” seat until lost to the Conservatives in December 2019, it was held by Ashton with a 36.4% majority at his last election in 1997.

He learned politics as a shop steward and as a member of Sheffield city council from 1962 until 1969. When first elected, he was the youngest member of the council, succeeding Roy Hattersley in that distinction. Hattersley would later write, in an affectionate and forthright foreword to Ashton’s first book of memoirs, Red Rose Blues (2000), that what he most admired about the author was his “absolute lack of discretion” and his inability ever to moderate his support or antagonism for any cause.

Such full-hearted enthusiasm was immediately evident at Westminster, where Ashton busily embarked on various backbench campaigns and established a high public profile as a national newspaper columnist, including briefly for the Guardian. He was parliamentary private secretary (PPS) to the sports minister Denis Howell (1969-70) and after Labour’s return to government did the same job for Tony Benn as secretary of state for industry and then energy. He was a strong leftwing supporter of Benn, encouraging him to fight Wilson as prime minister – “get into the ring like Cassius Clay and knock him out,” he advised Benn in 1975 – and although he was sacked as PPS for rebelling against the government in early 1976 he continued to do the job informally. He ran Benn’s campaign for the Labour leadership when Wilson unexpectedly resigned in the spring of 1976, and was surprised to be appointed as an assistant whip by the new prime minister, James Callaghan.

He lasted only a year in the whips’ office, but it was sufficient to provide material for a stage play based on the knife-edge existence of the Callaghan government. The play, A Majority of One, was well received after performances in Oldham and Nottingham in 1981; Ashton was fond of claiming that it was the inspiration for James Graham’s This House at the National Theatre 30 years later. During this period he published a political novel, Grass Roots (1977), which also garnered good reviews.

He fell out with Benn over the latter’s campaigns to introduce internal constitutional reforms within the Labour party, and thereafter became increasingly antagonistic both towards Benn and the party’s leftwing. He told a fellow Labour whip that he had explained to Benn: “The trouble with you, Tony, is you think the working class are noble savages when in fact there are just as many shits among the working class as anywhere else.” He criticised plans for mandatory reselection of MPs at successive party conferences and was slow-handclapped in 1980 when he warned that reselection could hasten defections to a breakaway party, as indeed happened when the SDP was launched the following year.

Ashton spent two years on the opposition frontbench as an energy spokesman from 1979. Thereafter he returned to the backbenches and sat on various select committees: trade and industry (1987-92), home affairs (1989-92), national heritage (1992-97) and on the select committee charged with modernising the House of Commons (1997-98). He chaired the all-party football committee from 1992 until he retired at the 2001 election, and was a passionate supporter of Sheffield Wednesday football club, of which he was a director from 1990 to 1999.

In 1998 Ashton was on the premises of a Thai massage parlour in Northampton during a police raid for suspected immigration offences. The following year it was disclosed that he had been questioned by police, although he had committed no offence. He wrote later in his memoirs that he had acted on a “crazy impulse”. The chapter was entitled All Political Careers End in Tears. In retirement he founded the Association for Former Members of Parliament in 2001. He also published a second book of Sheffield memoirs, Joe Blow – his childhood nickname – in 2014, and donated the proceeds to the Salvation Army. He was appointed OBE in 2007.

He married Margaret (Maggie) Lee, a former secretary at the Sheffield Brightside and Carbrook Co-operative Society coal depot, in 1957. She died in 2014 and he is survived by their daughter, Lucy.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion