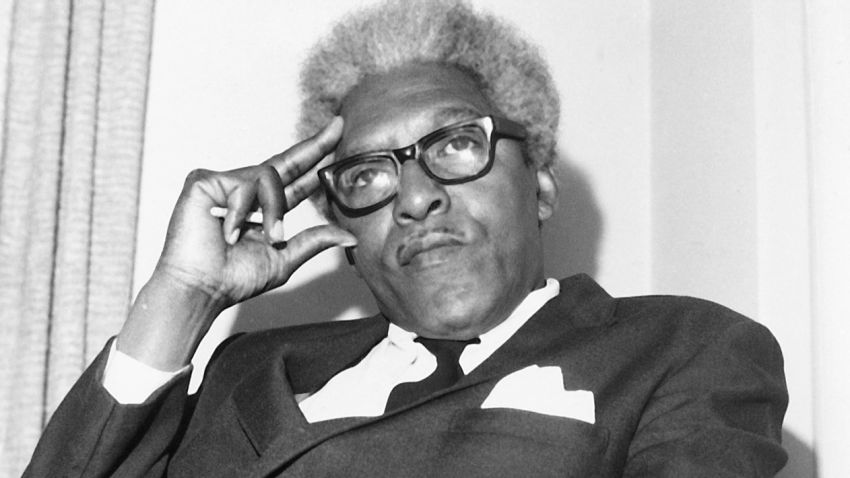

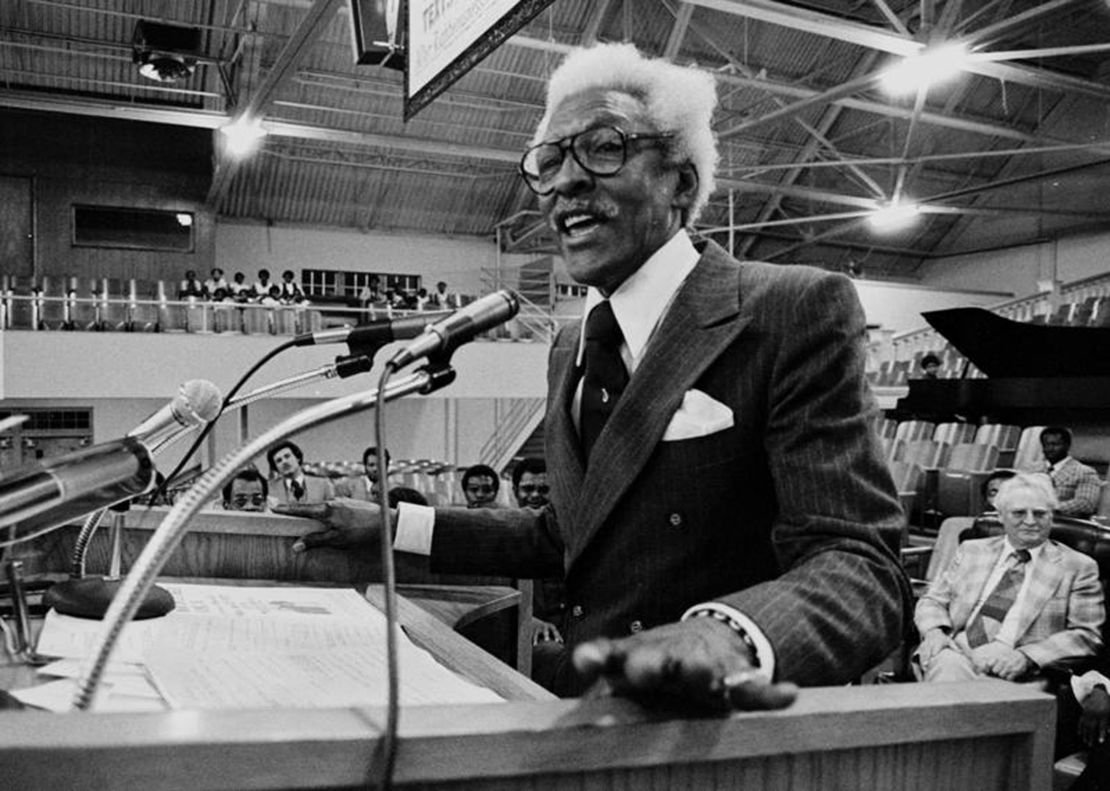

As a civil rights leader and an advocate for justice, Bayard Rustin was no stranger to being behind bars.

He was arrested for his anti-war efforts in opposition to World War II. He was arrested for protesting segregation laws in the Jim Crow-era South. But in 1953, he was arrested for reasons outside his activism — for having sex with men.

Rustin was jailed on a “morals charge.” He was eventually convicted of misdemeanor vagrancy and was sentenced to 60 days in jail. The offense landed him on the sex offender list, cost him jobs and was used to delegitimize the civil rights movement by people like segregationist Sen. Strom Thurmond, who read Rustin’s arrest record on the Senate floor.

On Tuesday, 67 years after that arrest and 33 years after his death, Rustin received a pardon from California Gov. Gavin Newsom.

“Mr. Rustin was criminalized because of stigma, bias, and ignorance,” Newsom said in the pardon. “With this act of executive clemency, I acknowledge the inherent injustice of this conviction, an injustice that was compounded by his political opponents’ use of the record of this case to try to undermine him, his associates, and the civil rights movement.”

It’s part of an initiative to pardon people prosecuted for being gay

Rustin’s pardon is part of a new initiative from Newsom’s office to grant clemency to people who were prosecuted in California for being gay, inspired by a push from leaders of the California Legislative Black Caucus and the California Legislative LGBTQ Caucus.

“In California and across the country, charges like vagrancy, loitering, and sodomy have been used to unjustly target lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) people,” a news release from Newson’s office reads.

“Law enforcement and prosecutors specifically targeted LGBTQ individuals, communities and community spaces for criminal prosecution. Now, as a proudly LGBTQ-allied state, California is turning the page on historic wrongs.”

California repealed a law that criminalized consensual sex between same-sex adults in 1975. And starting in 1997, people convicted of engaging in consensual sex with other adults could request that they be removed from California’s sex offender registry. But those actions didn’t affect convictions or amount to a pardon.

“Generations of LGBT people — including countless gay men — were branded criminals and sex offenders simply because they had consensual sex,” said state Sen. Scott Wiener, chairman of the California Legislative LGBTQ Caucus. “This was often life-ruining, and many languished on the sex offender registry for decades. The Governor’s actions today are a huge step forward in our community’s ongoing quest for full acceptance and justice.”

Assemblywoman Shirley Weber, the chairwoman of the California Legislative Black Caucus, said the pardon would finally remove a stain on Rustin’s legacy.

“The Arc of Justice is long, but it took nearly 70 years for Bayard Rustin to have his legacy in the Civil Rights movement uncompromised by this incident,” Weber said in a statement. “Rustin was a great American who was both gay and black at a time when the sheer fact of being either or both could land you in jail.”

Rustin’s legacy

Rustin led and organized some of the most pivotal protests of the civil rights movement. Most famously, he was the mastermind behind the 1963 March on Washington.

He was the main person who pushed the movement — and Martin Luther King — toward nonviolent ideas and tactics. Rustin traveled to India in 1948 to learn more about pacifist ideas and helped introduce those teachings to King.

Following the success of the Montgomery bus boycott in 1956, Rustin became a close confidant of King.

Rustin played a significant role in the formation of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, known as SCLC.

Though former President Barack Obama awarded Rustin the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2013, he remains much less known when compared to his civil rights movement peers. Some academics argue this is due to the homophobia of the time.

CNN’s Leah Asmelash contributed to this report.