BDSM

You Consented. Now, Relax. It's Play Time!

Sexual activities that fail on the moral scale.

Posted April 10, 2018

Agreement to sex is not consent. "Consent" is shorthand for "voluntary informed consent." If you say "yes" to sex because you are threatened, forced, or coerced, your agreement is not consent. Being deceived about what's about to happen can make you unable to consent by agreement altogether.

This raises the question: Is truly consensual sex ever morally wrong?

It can be. Suppose Jordan and Alexis are about to be intimate. Alexis is wearing very feminine clothing. So Jordan believes Alexis is a woman. Alexis is in fact an androgynous male but he hasn't told Jordan because he believes Jordan is heterosexual and would have said "no," if told. Unbeknownst to Alexis, Jordan is bisexual, and gender doesn't matter to him. In fact, Jordan would never expect anyone to talk about their gender, and he would definitely never ask.

In the envisaged scenario, Jordan would have said "yes," even if Alexis had revealed his gender. So, Jordan's agreement counts as consent, in spite of the fact that Alexis deceived Jordan.

Even so, it's wrong for Alexis to withhold potentially sensitive information from Jordan with the only aim of getting him to say "yes," and then proceed once he agrees. As Alexis have ill intentions, his actions are morally questionable.

Sexual Deceit and the Trolley Problem

What makes sexual deceit problematic is that it is difficult to reconcile with our common sentiment that we ought to respect each other. According to Kant's categorical imperative, it is morally wrong to treat people merely as a means to an end. Our treatment of others requires respecting their personhood by recognizing their intrinsic value as subjects.

In our envisaged example, Alexis mistakenly believes Jordan is heterosexual and would say "no," if told that Alexis is male. Alexis succeeds in deceiving Jordan, and while the deception is not what makes Jordan agree, it is nonetheless what makes him agree in the mind of Alexis. Attempting to use sneaky tactics to prevent a "no" to sex is to treat the other merely as a means to an end (one's own pleasure). This is so, even if it so happens that the other would truly have enjoyed themselves.

We humans are on average quite sensitive to the Kantian categorical imperative and often adhere to it. Yet we are tempted to deviate when you can do a lot of good without directly causing harm.

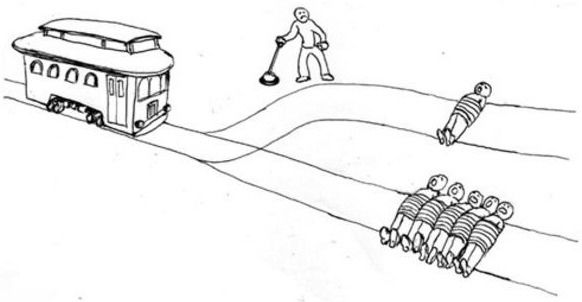

The so-called Trolley Problem is a good illustration of our sensitivity to Kant's imperative. Here is the original trolley case:

A runaway trolley is hurtling down the railway tracks. Five people are tied up and unable to move on the tracks ahead. The trolley is headed straight for them. You are standing in the train yard, next to a lever. If you pull the lever, the trolley will switch to a side track. However, you notice that one person is tied up on the side track.

You have two options: (i) Do nothing and the trolley kills the five people on the main track. (ii) Pull the lever, diverting the trolley onto the side track, which kills one person but saves five.

How will you proceed?

In studies of these cases, most research participants subjected to this dilemma say that they would pull the lever, which would kill one but save five (Greene, et al., 2001, 2004, 2008). Their moral choice satisfies the utilitarian principle that you should aim at maximizing wellbeing and minimizing suffering. Pulling the lever kills one person and saves five, whereas not pulling it kills five and lets one live. So, you are more likely to increase wellbeing if you pull the lever than if you do not. People's inclination to pull the lever in this case thus seems to be a result of thinking in accordance with the utilitarian principle.

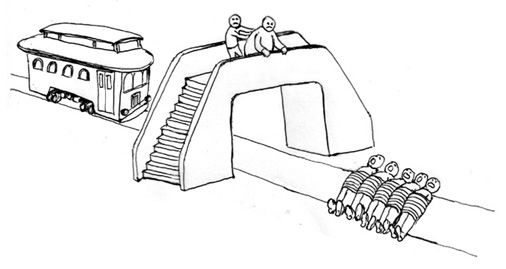

Here is the second trolley case:

As before, a runaway trolley is about to hit five people on its track. You are on a bridge overlooking the track. You know that you can stop the trolley and save the five people by putting something very heavy in front of it. As it happens, a very fat man is standing next to you. You only way to stop the trolley is to push him over the bridge and onto the track, killing him to save the lives of five others.

Should you proceed?

Despite the analogy between the two scenarios, most people do not respond in the same way to this dilemma. Even people who happily switch the lever in the first scenario allege that they would not push the fat man in order to save the five.

This finding suggests that we give more weight to Kant's categorical imperative when it's salient to us that we must harm a person by active force of our own in order for us to prevent the death of others (Greene, et al., 2001, 2004, 2008).

To recap: while we are generally sympathetic to utilitarian principles, our attraction to Kant's imperative overrides our utilitarian inclinations once it is made salient that saving lives requires intentionally killing an innocent man. Murder violates the categorical imperative. So, our unwillingness to push the man onto the tracks indicates that we only believe in maximizing utility when this is compatible with respecting people.

In the context of sex, actively taking steps to use another person merely as a means to one's own sexual satisfaction displays a lack of consideration of the other person as an autonomous agent. So, it can be expected that we will tend to disapprove of active attempts to get consent by deceit.

Cannibalism

Consensual sexual activities can by their very nature be squarely at odds with respect for persons. Disregarding another's dignity whether the person is healthy and alive or is about to die entails failing to respect them as persons in their own right. This failure to be respectful is sometimes rooted in a general tendency to devaluate others, as is typical in antisocial personality disorder--or psychopathy--and narcissistic personality disorder.

This may well have been what was going on when 42-year old Berlin computer expert Armin Meiwes had sex with 43-year-old Berlin engineer Bernd Brandes and then consumed him alive.

Meiwes had for a long time fantasized about eating someone alive and eventually decided to do give it a try. After several failed attempts to find a willing person through advertisement, Brandes came out of the woodwork. After mutual agreement to what was about to happen, Meiwes went through with his plan.

With time the German police discovered what had happened. After an investigation, the case went to court. However, the case was complicated by the fact that cannibalism is not illegal in Germany, and that Brandes consented to everything in advance of any potential wrongdoing. Meiwes was, however, eventually convicted of manslaughter and imprisoned for eight years.

Despite legal outcomes, most people have a very strong feeling that what Meiwes did was extremely unethical. The act of eating another person for the sake of sexual pleasure is an extreme case of using another person without the recognition of his or her value as a subject. Brandes didn't die gracefully. He died in one of the most undignified ways imaginable.

Prostitution

Kant's categorical imperative may seem to rule out other more widely accepted forms of consensual sex, like prostitution or sadomasochism. If you pay someone to have sex with you, aren't you using them as a means to an end? Aren't you using them as a tool for sexual pleasure?

Although it may seem that the Kantian imperative has the same consequences for prostitution and sadomasochism as it does for sex killing, there are in fact vast differences between them.

In the case of Meiwes' sexualized cannibalism, the planned ritual was essentially such as to take away a man's dignity together with his life. This, however, is not so in the cases of prostitution and sadomasochism.

Paying the pizza delivery guy for your delivery does not thereby make you disrespect him as a person. Upon seeing him sweaty and out of breath as he hands you the pizza, it may strike you that you really respect him as a person. Although you pay him for his services, this does not take away from his dignity.

Similar remarks apply to prostitution. If you use a prostitute, you pay him or her to give you sexual pleasure. Although these kinds of business exchange are still frowned upon in today's culture, societal disrespect for prostitutes does not translate into a lack of respect for a specific prostitute who satisfies your sexual needs. As prostitution is compatible with respect for persons, the Kantian imperative does not imply that it is morally subpar.

Sadomasochism

What about sadomasochism? Sadomasochism normally involves a person in the sadist role degrading, humiliating or physically hurting the submissive person for the sake of the sadist’s own satisfaction.

In sadomasochistic rituals, the participants experience abuse and humiliation. As salience of the intention to harm can make us more sensitive to the Kantian imperative, we might expect sadomasochistic practices to invoke a feeling of moral condemnation of the practice. Yet its prevalence in many subcultures and emergence in popular culture testify to its status as a deviant yet morally acceptable way of experiencing sexual pleasure.

Why do we not react like angry Kantians toward sadomasochism?

One reason may be that sadomasochism does not involve genuine disrespect for another person’s moral personhood (see e.g., Langdridge & Barker, 2007). Studies of sadomasochism in natural environments confirm this. In a multi-year study of sadomasochism in San Francisco, Margot Weiss (2011) found that although sadomasochistic activities involve a dominant/submissive dynamic that often simulate power differentials relating to race, class, gender, sexual identity and ethnic cleansing, practitioners tend not to embody or act on any extremist attitudes.

Sadomasochism in its typical forms can be viewed as a kind of make-believe role play (Stear, 2009). It is similar in its imitation of reality to other make-believe games such as the games children play when pretending to be ninjas, princess-warriors or cowboys as well as the games adults play when engaging with fiction as spectators or readers (Stear, 2009).

Sadomasochism understood as make-believe is consistent with the dominant person’s recognition of the submissive person as an intrinsically valuable subject. So, unlike extremely deviant sexual activities, such as sexual cannibalism, sadomasochism may live up to the standards of Kantian morality.

Berit "Brit" Brogaard is the author of On Romantic Love.

References

Greene, J. D., Sommerville, R. B., Nystrom, L. E., Darley, J. M., & Cohen, J. D. (2001). “An fMRI Investigation of Emotional Engagement in Moral Judgment,” Science 293: 2105-2108.

Greene, J. D., Nystrom, L. E., Engell, A. D., Darley, J. M., & Cohen, J. D. (2004). The Neural Bases of Cognitive Conflict and Control in Moral Judgment,” Neuron 44: 389-400.

Greene, J. D., Morelli, S. A., Lowenberg, K., Nystrom, L. E., & Cohen, J. D. (2008). “Cognitive Load Selectively Interferes with Utilitarian Moral Judgment,” Cognition 107: 1144-1154.

Langdridge D. & Barker, M. (eds.) (2007). Safe, Sane and Consensual: Contemporary Perspectives on Sadomasochism, New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Stear N-H (2009). “Sadomasochism as Make-Believe,” Hypatia 24(2): 1–38.

Weiss, M. (2011). Techniques of Pleasure: BDSM and the Circuits of Sexuality, Durham and London: Duke University Press.