The Forgotten Handmaid's Tale

Twenty-five years after its release, the movie adaptation of Margaret Atwood’s dystopian novel has been largely disremembered. Is the book still too radical for film?

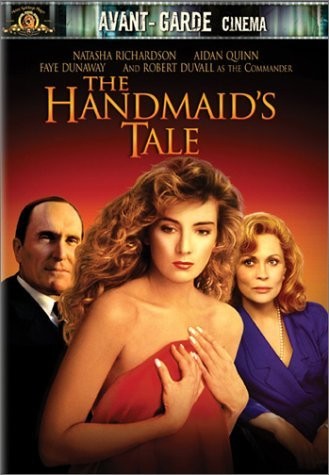

30 years ago, the Canadian author Margaret Atwood published The Handmaid’s Tale, a dystopian feminist novel set in a futuristic America run by religious fundamentalists. Pollution and sexually transmitted diseases have rendered the large majority of people infertile; the few women who can still reproduce are trained as “handmaids” and forcibly sent to serve wealthy and powerful men by bearing them and their wives' children. The novel, Atwood’s best-known work, has since become a modern classic, and a staple on English literature reading lists. It’s sold millions of copies and “appeared in a bewildering number of translations and editions,” as Atwood wrote in The Guardian earlier this year. The book has been adapted into plays, and even an opera. In March 1990, five years after its release, The Handmaid’s Tale was released as a movie, with a script by Harold Pinter, and stars including Natasha Richardson, Faye Dunaway, and Robert Duvall. But while the novel hasn’t been out of print in the three decades since its debut, the film has been almost entirely forgotten, to the point where copies of it are so rare they sell for upwards of $100 on Amazon.

In many ways, the movie adaptation was ill-fated from the start, even with the wide acclaim the book had received. In 1986, Atwood sold the rights to the producer Daniel Wilson, partly because Wilson had tapped Pinter and the director Karel Reisz to lead the project. The playwright had previously worked with Reisz on The French Lieutenant’s Woman, which starred Meryl Streep as a strong-willed woman condemned as promiscuous by a repressive society, and was nominated for five Academy Awards. But despite the talent attached and the success of Pinter and Reisz’s previous collaboration, no studio wanted to touch it. “During the next two and a half years, Wilson would take the Pinter script to every studio in Hollywood, encountering a wall of ignorance, hostility, and indifference,” writes the Canadian journalist Sheldon Teitelbaum. Movie executives declined to back the project, stating “that a film for and about women … would be lucky if it made it to video.”

In 1988, the actress Sigourney Weaver—a huge star following the release of Alien and Ghostbusters—committed to the project, and although Reisz was no longer available, the film finally found a studio (Cinecom) and a new director, the German auteur Volker Schlondorff. But Weaver had to drop out when she became pregnant, and Schlondorff and Wilson found it increasingly difficult to find a star willing to play Offred, the book’s narrator (named literally “Of Fred,” for the commander she belongs to). Although Offred is an astonishing character with a rich interior monologue incorporating fierce intelligence, compassion, and violent fantasies of revenge against her oppressors, many actresses feared the stigma of being associated with such an explicitly feminist work. “Schlondorff is reported to have approached almost every American actress to take over the part of Offred … yet every one of them declined,” writes the academic Reingard M. Nishick. Eventually, the British actress Natasha Richardson accepted the part. Richardson, a daughter of the actress and socialist Vanessa Redgrave, had activism in her blood, but even she was reportedly wary about taking on the role.

Where Reisz was dedicated to realism, Schlondorff was a pioneer of the New German Cinema movement who was eager to break into Hollywood. The Handmaid’s Tale as he interpreted it was a thriller—a sexually charged and vivid drama without the nuance or emotional depth of the source material. Without her interior monologue (Richardson later complained that Pinter “has something specific against voiceovers”), Offred becomes considerably more enigmatic and less human, even though the movie, unlike the book, identifies her birth name as Kate. Although the book is told entirely from Offred’s perspective, the film barely gives her more lines than other characters. Initially, after her husband is shot at the border and her daughter is taken as the family tries to flee from the repressive Republic of Gilead, Kate seems oddly blank, staring vaguely out a window as she watches infertile women get loaded into a truck labeled “Livestock.” There’s little sense, as is made explicit in the book, that she’s being drugged so that she doesn’t erupt in grief and rage at the loss of her child.

The most subtle moment in the film comes in the opening scenes, as Kate exits the driver’s seat and lets her husband take the wheel as the two approach the border. It’s a quiet nod at Gilead’s oppressive regime that’s soon forgotten as the movie enters the realm of melodrama, lighting scenes in vivid shades of blue and green, and incorporating a moody synthesized score better suited to a 1980s horror film. The moment where Offred dispassionately describes taking part in a “ceremony” with the commander and his wife—in which he has sex with her while she lies in his wife’s lap—becomes a violent rape scene where Kate sobs while shrouded in a red veil. Afterwards, Kate runs to her room, pulls off her nightgown, and presses her breasts against the window while gasping for air—as witnessed by the household chauffeur, who motions her quickly away, since it’s a deranged move she’d almost certainly be executed for if caught.

And yet, despite Schlondorff’s embrace of schlocky visual effects and headbangingly obvious symbolism, the film isn’t all that bad. The script is minimalistic in a typically Pinterian style (even though the playwright later declined to claim it as his work, saying that it had been considerably altered), meaning that more is said between the lines than is actually verbalized. Although the approach is markedly different from the confessional monologues Atwood gives Offred, the dialogue is spare and taut. Richardson manages to communicate Kate’s depth and sensitivity with very little to work with, and her performance contrasts effectively with Faye Dunaway’s cold steel as the commander’s wife, Serena Joy. Serena, a former televangelist, snips flowers from the earth with indifferent precision, and gazes serenely at Kate while dangling the whereabouts of her daughter in front of her like a treat in front of a dog. She’s also the only female character who’s seen mourning her former professional life, as she watches videos of herself singing “Amazing Grace” and conducts the old Serena with an unreadable expression and a lit cigarette.

The film mines rich horror out of the fact that the book’s primary villains, even in a state-mandated patriarchy, are female. Victoria Tennant plays Lydia, one of the fussy and sadistic “aunts” who control and train the handmaids before they’re assigned to houses. “Why do you think God made you a woman?” she shouts at a nun who insists she won’t violate her vows of celibacy. Another aunt drags a screaming girl to the dinner table after torturing her bloodied feet, while Aunt Lydia chastises the girl for "defiling" herself. With the women doing the dirty work, the men can afford to be generous. Compared to the chilly Serena, Robert Duvall’s Commander is half benevolence, half menace, alternately inviting Kate to his study for strawberries and Scrabble, and then violently kissing her as she writhes in protest.

The movie also renders Atwood’s more horrific scenes in vibrant color, showing the wives gathered in royal blue at a garden party to celebrate a handmaid giving birth in full view, and the handmaids, dressed in their crimson, full-length gowns, gouging a political prisoner to death with their hands after being told he’d raped one of their pregnant sisters. The book’s public hangings, set in Harvard Square, were filmed on the grounds of Duke University. And the camera lingers on the mangled hands of Kate's friend Moira (Elizabeth McGovern) after Kate encounters her at a brothel the Commander has brought her to on a whim. “We don’t need hands and feet for our purposes,” Moira elucidates, her bravado shaken for a second.

Nevertheless, the film was panned. “The movie seems equally angry that women have to have children at all, and that it is hard for them to have children now that men have mucked up the planet with their greedy schemes,” wrote Roger Ebert. Rolling Stone’s Peter Travers described the "ceremony" as “about as erotic as a gynecological exam,” and complained that the movie had “narrowed the focus to [Male Chauvinist Pigs] who like to put women in their place.” The film’s vision of the future, Entertainment Weekly’s Owen Glieberman wrote, “is so poisonous and mechanical that you have to wonder: Is this really what our society is threatening to turn into, or is Atwood just exorcising her own fear and loathing?”

Two female reviewers were less offended. “As visions of a hellish, dehumanizing future go, this one could never be mistaken for a man’s,” wrote The New York Times’ Janet Maslin. “With its devilish attention to polite little touches, its abundant bitchiness … The Handmaid’s Tale is a shrewd if preposterous cautionary tale that strikes a wide range of resonant chords." The Washington Post’s Rita Kempley praised the story of “surrogate motherhood run amok in a society dominated by iron-fisted pulpit thumpers turned fascist militarists,” even while acknowledging that “Schlondorff seems as uncomfortable in this feminist nightmare as a man in a lingerie department.”

The film was an undeniable failure, grossing less than $5 million against a $13 million budget. Its status as a catastrophe seems to have prevented any other producers from tackling new film or TV adaptations, even while the book continues to endure both as a model of speculative fiction and across a variety of artistic mediums. “The general characteristics of Schlondorff’s adaptation could partly be put down to the necessity of a Hollywood film, made to capture the interest of multitudes rather than that of film (or literature connoisseurs),” writes Nischik. But the 1990 film pleased neither Atwood’s fans nor moviegoers, opting for a sensationalist, stylized rendition of religious fascism at work. Since then, a number of Atwood’s imaginings (themselves ripped from American history) have manifested in reality, prompting the question of what insight might be gained from a new, more faithful Handmaid’s Tale. Still, it’s equally possible that, even 25 years later, neither audiences nor the film industry is ready yet.

Sophie Gilbert is a staff writer at The Atlantic. She was a finalist for the 2022 Pulitzer Prize in Criticism.