We're only part way through The New Yorker Festival's panel on investigative journalism and already Jane Mayer has left the stage. It's Oct. 6, the day the Senate will meet to vote on the confirmation of Judge Brett Kavanaugh, and Mayer, as she explains it, has developed "The Kavanaugh Cough." The sickness can only be attributed to weeks of non-stop reporting and writing on the now-confirmed Supreme Court Justice and the various sexual assault allegations made against him. And it has, for the moment, caused her to leave the stage in a fit of coughing.

Mayer is The New Yorker's chief Washington correspondent, and along with Ronan Farrow, she broke news on the second public allegation against Kavanaugh. In an exclusive story, Deborah Ramirez accused Kavanaugh of sexual misconduct when the two were at Yale University, saying he exposed himself to her at a party. Then, after a brief FBI investigation was requested to look into the allegations, Mayer and Farrow wrote about several people who tried to report information to the FBI but were never formally questioned.

It's clearly a solid partnership, and one that has a habit of making history. Earlier this year, they co-published a story about physical abuse allegations against New York's former attorney general Eric Schneiderman. He resigned just hours later.

For Mayer, it's all a natural extension of her previous work. She's reported on, and written books about, billionaires who've helped shape the radical right (Dark Money), the war on terror (The Dark Side), and the confirmation of Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas, who was similarly accused of sexual harassment by Anita Hill (Strange Justice).

It's a career built on holding truth to power, but, as she clarifies, she's not an activist. Once she's recovered from her coughing fit and retaken the stage, she tells the festival crowd, "It's not resistance. It's reporting."

Ahead, she tells ELLE.com about tag-teaming breaking news, nuance in the age of Twitter, and whether she can actually ever wind down:

What have been the main differences between reporting on Clarence Thomas and Anita Hill versus Brett Kavanaugh? Did you learn anything in your reporting of Thomas that you applied to your reporting of Kavanaugh?

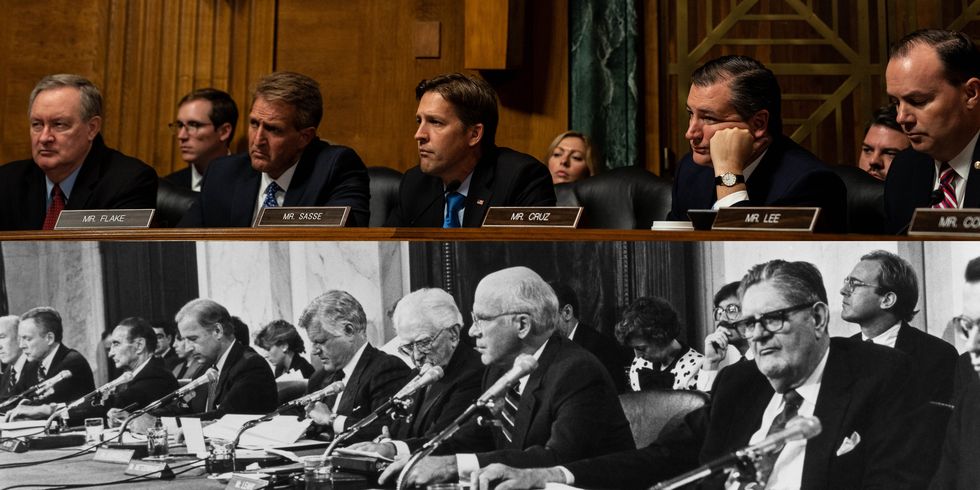

I think I was really advantaged by having covered the Thomas-Hill confirmation battle because basically I’d seen this movie before. In fact, I’d watched as several of the same senators had disrespected Anita Hill a generation ago, and there they were, still questioning the woman’s credibility.

So having watched this before, I knew that key issues would be whether the judge had a pattern of similar behavior, since that helps establish who is telling the truth when there is a standoff, and whether there were credible corroborators on either side. Knowing this is why Ronan Farrow and I were so alert to the significance of other accusers, such as Deborah Ramirez. Her allegation showed that, if true, yes, there was a pattern of misconduct, and likely another side of the judge.

Similarly, it was very important to get Elizabeth Rasor on the record. She was the college girlfriend of Brett Kavanaugh’s best high school friend, Mark Judge. Kavanaugh has used Judge as one of his corroborators and a character witness attesting to the impossibility that they could have mistreated girls in high school (Judge has said they attended an all-boys school, so they never “rough-housed” with girls). To the contrary, Rasor told me that Mark Judge told her that he and his high school friends had taken turns having sex with the same inebriated woman. Rasor, who is now a teacher and a mother, came forward, she said, because she couldn’t stand to sit by and watch Judge lie. Judge’s lawyer said he categorically denied it, but Rasor offered to give a signed statement to the F.B.I.

Has it been different, or even more emotional, to report on sexual abuses of power versus abuses of power in politics and finance? We don’t tend to think of people like Deborah Ramirez as whistleblowers in the same way.

As a reporter, my heart goes out to the powerless and vulnerable who try to tell the truth in the face of great risks, no matter who they are. As a woman, I do feel empathetic toward other women, if they are telling what appears to be the truth. I admire their guts, and their belief that speaking up can right wrongs, and even sometimes change history.

The credibility of the media has been consistently under attack since President Trump took office. How does that type of scrutiny and skepticism affect you and your reporting? Are sources less likely to talk to you?

I’m pretty thick-skinned by now, so slough off most of the partisan flak as just political hot air. I’ve found that nothing speaks louder than just getting the story, and that if it’s right, most people will respect it, and sources will flock to add more. That’s certainly what happened with the Kavanaugh reporting. My phone was ringing and pinging with so many calls and text messages I could barely keep up.

You’ve shared a byline with Ronan Farrow on many of your recent investigations. How does that partnership work logistically? What makes you decide that you want to work with someone else on a story?

Ronan’s been a fantastic reporting partner. In the past, The New Yorker had almost no double bylines. The website, though, requires more speed, especially on competitive breaking news stories. So it makes sense to team up.

There’s no master plan, but Ronan has a gift for getting people to confide in him about sexual abuse, so he’s handled some of the most difficult interviews of the victims. My strength is holding those in power to account, conveying the political context, and writing the stories compellingly. But basically, we both have great respect for each other and divide up the work easily as any tag team would. We often work on a shared Google doc where we can literally write collaboratively. We also make each other laugh, thank goodness.

What’s it like to be a veteran reporter working with someone who’s come up in the internet age?

It’s a ton of fun working with someone as young and talented as Ronan, though I’ve teased him that he’s a bit of a slacker. I mean, he’s 30 and has a Rhodes Scholarship and a Pulitzer, but isn’t it time he won Wimbledon, too?

How has keeping up with the internet news cycle changed your job or how you react to news?

It requires working at incredible speed, which I kind of hate. I went to The New Yorker because it was so elegant, witty, and thoughtful, and it’s hard to be any of those things in a tweet. But you have no choice, really. Things move unbelievably fast.

How do you respond to people who think Ronan gets all the credit for your joint bylines?

As I’ve said before, truly my last worry is getting byline credit. All Ronan and I care about is getting the story. I’m incredibly privileged to have this job and such amazing people to work with.

How do you relax and unplug from the news cycle?

I am really lucky—I have a fantastic husband, daughter, dog, and friends, and a lot of other interests. If I really want to unplug, though, I have been known to get a pedicure with my daughter or a friend at one of those places where they serve a glass of champagne at the same time!