Seventy years ago on Thursday, the Empire Windrush sailed imperiously into Jamaica’s capital, greeted by throngs of spectators. Among them were musicians and boxers, craftsmen and clerks, all chasing dreams of a better life in the mother country.

The 70th anniversary should have been a moment of national pride on both sides of the Atlantic. Instead in Jamaica there is deepening resentment over the treatment of those who left for Britain, amid the spiralling consequences of what has become known as the Windrush crisis.

“I will never trust the English again,” said Melvin Collins, a 72-year-old former Midlands youth worker, who has been stranded in Montego Bay since his passport was revoked without explanation in 2015. He, like many others, is desperately seeking answers from the British government.

From Kingston to Negril, families recall villages being decimated by the long exodus to Britain. Others recount the racism they faced on arrival. Those who worked for years to rebuild Britain from the ashes of war feel the sharpest betrayal.

Q&AWhat is the Windrush deportation scandal?

Show

Who are the Windrush generation?

They are people who arrived in the UK after the second world war from Caribbean countries at the invitation of the British government. The first group arrived on the ship MV Empire Windrush in June 1948.

What happened to them?

An estimated 50,000 people faced the risk of deportation if they had never formalised their residency status and did not have the required documentation to prove it.

Why now?

It stems from a policy, set out by Theresa May when she was home secretary, to make the UK 'a really hostile environment for illegal immigrants'. It requires employers, NHS staff, private landlords and other bodies to demand evidence of people’s citizenship or immigration status.

Why do they not have the correct paperwork and status?

Some children, often travelling on their parents’ passports, were never formally naturalised and many moved to the UK before the countries in which they were born became independent, so they assumed they were British. In some cases, they did not apply for passports. The Home Office did not keep a record of people entering the country and granted leave to remain, which was conferred on anyone living continuously in the country since before 1 January 1973.

What did the government try and do to resolve the problem?

A Home Office team was set up to ensure Commonwealth-born long-term UK residents would no longer find themselves classified as being in the UK illegally. But a month after one minister promised the cases would be resolved within two weeks, many remained destitute. In November 2018 home secretary Sajid Javid revealed that at least 11 Britons who had been wrongly deported had died. In April 2019 the government agreed to pay up to £200m in compensation.

By the end of 2020, victims were describing the long waits and 'abysmal' payouts with the scheme, and the most senior black Home Office employee in the team responsible for the Windrush compensation scheme resigned, describing it as systemically racist and unfit for purpose.

The Jamaican government has contacted some Windrush victims in the past week, as it scrambles to remedy cases where people have been wrongly expelled from Britain. Yet, four weeks on from a government minister’s pledge to have all cases resolved within a fortnight, there is little official indication about the true scale of the problem on either side of the Atlantic.

Jamaica’s two biggest newspapers, the Gleaner and the Observer, have run advertisements from the country’s ministry of foreign affairs appealing for Windrush cases to contact its helpline.

All across the island, charities, lawyers and homeless drop-in centres have been left mystified by the fate of the elusive 63 deportees confirmed by the new home secretary, Sajid Javid. None have come to the attention of the handful of dedicated – and overstretched – Jamaican charities working in that field, including the National Organisation of Deported Migrants (NODM), which is funded by the British high commission.

In a rundown office block in downtown Kingston, hidden among streets of boarded-up or burnt-down buildings, NODM’s president, Oswald Dawkins, explains why those removed from Britain have not yet been found: the stigma. “A lot of people who are deported, they don’t necessarily come out of their shell. They don’t want people to know they’ve been deported so a lot of time they won’t make contact with agencies or even individuals,” he said.

There is a famous song by the reggae star Buju Banton, himself a deportee, about the shame attached to those who return to Jamaica penniless.

The stigma is most keenly felt by the older generation, according to Dawkins, who would include Windrush-era migrants who arrived in Britain before 1973 and have been deported since 2002.

Dawkins said deportees – who are mostly from the US, Britain and Canada – would feel too ashamed to ask friends or relatives for help in their ancestral villages so they often ended up homeless, usually disappearing into the chaotic human slipstreams of Kingston or Montego Bay.

This is what happened to Ken Morgan, whose British passport was confiscated by immigration officers when he visited Jamaica for a family funeral 25 years ago. The 68-year-old former English teacher, from Walthamstow, was destitute and isolated. Yet shame stopped him returning to Clarendon, the parish where his family lived, and instead he stayed in temporary accommodation close to the British high commission, a fortress-like building set behind three-metre-high walls protected by spikes, barbed wire and a 24-hour security checkpoint.

“When you leave here and go to England or Canada or United States, you’re technically supposed to come back rich. You’re supposed to come back and buy a big house,” Morgan said. “Otherwise why did you go? What are you doing there, if you don’t come back with money?” His sharp east London accent also held him back: “The worst thing was the way I spoke. I couldn’t open my mouth. I can blend in here physically, I can just look like everybody else. But as soon as I open my mouth, I’m not supposed to be at that level. You can’t be broke.”

The focus on deportees could mask the true scale of the problem, according to charity workers, since those kicked out of Britain are usually offered more official help than the many more who are prevented from trying to return to the UK. It is those stopped from returning – usually for minor paperwork errors not of their own making – that make up the vast majority of Windrush cases in Jamaica, according to Jennifer Housen, a Kingston-based immigration lawyer who said she had dealt with more than a hundred “hostile environment” cases in the past 10 years.

“How it affected most people is them coming on holiday here and not being able to go back [to Britain],” she said. “I’ve had people here who’ve lost their homes because they’ve had to spend weeks and weeks and weeks here trying to prove their identity.”

ProfileHow the Guardian broke the Windrush story

Show

In November last year, Paulette Wilson (left), who has lived in the UK for more than half a century, spoke to the Guardian's Amelia Gentleman about her treatment at the hands of the Home Office - and revealed that she had been held at Yarl’s Wood detention centre and threatened with deportation. It was the first of a series of stories that developed a picture of how many members of the Windrush generation were being mistreated by the government under the so-called ‘hostile environment’ policy. By February, with other examples mounting, the government had relented in Wilson’s case, but faced acute criticism from Caribbean diplomats who urged the Home Office to adopt a “more compassionate” approach.

In March the story of Albert Thompson - who had lived in Britain for 44 years but was told to produce a passport or face a bill of £54,000 for cancer treatment - forced attention back to the growing crisis. After the Guardian reported a string of additional cases matters came to a head when Theresa May refused to meet with Caribbean diplomats to discuss the issue, prompted fury among opposition MPs and a wider media backlash. After days of negative publicity, the then home secretary, Amber Rudd, and May were forced to change tack and issued apologies, promised reforms – and eventually gave the Windrush generation a fast-track to citizenship.

Housen, a former West Midlands police officer, has only ever come across one deportee. His name is Errol Campbell, a 59-year-old aerospace engineer who was deported to Jamaica five years ago for allegedly falsely obtaining a British passport. It is a charge he denies and which Housen is fighting to overturn.

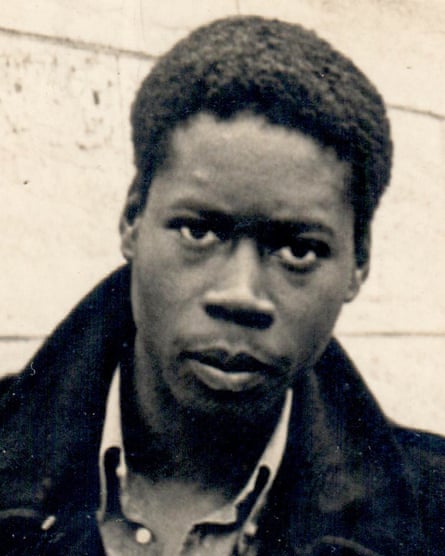

Like many Windrush cases, Campbell’s is complex. He was born in London on 24 May 1959 but his birth was not registered at the time because Campbell’s father did not believe he was his son. Campbell went to primary school in London but returned, aged six, to Jamaica with his mother and his three siblings when her marriage broke down.

However, without any Jamaican identification he could not go to secondary school. Without any birth certificate, he could not open a bank account, find work, register to vote, or apply for a passport. He was stuck. While his siblings and mother returned to Britain, Campbell was left in limbo in Jamaica. He lived with his grandmother, doing odd jobs to save enough money to return to his family in England and finally prove his British identity.

In 2001 Campbell obtained a fake Jamaican passport and used it to fly to Britain. “I was desperate. I just wanted to get home,” he said, when we meet on a humid night in Kingston. Having returned to Britain, in 2007 he amassed sufficient evidence to register his birth and was then granted a British passport following an interview with Home Office officials at Lunar House in Croydon.

Two years later, Errol was convicted of a driving offence and his world began to unravel. Investigations found he had used a fake Jamaican passport to travel to Britain. He was then accused of using this fake Jamaican passport to fraudulently obtain a British passport. He was held in an immigration removal centre for three days then released on bail for six months. Two years later he was convicted of fraudulently obtaining a British passport and jailed for 15 months, despite evidence submitted by his lawyers and relatives that his British passport was legitimate and he was truly a British citizen. He was deported in 2013.

Campbell has been in limbo in Montego Bay ever since. Unable to work without Jamaican identification yet unable to return to Britain, he is effectively a citizen of nowhere. He only has a roof over his head thanks to his wife, Jennifer Somers, a nurse in London, who sends him money for rent, food and clothes. “Without me he wouldn’t be able to survive, he’s got no one to help him,” said Somers.

Despite missing out on most of his education, Campbell taught himself maths using school books and later completed an engineering course at Stratford College in east London. Before he was deported he worked as a test engineer on helicopters and Eurofighter Typhoon fighter jets for Ametek Aerospace in London. Now he cuts a broken figure. “I just feel like I’ve become not a human. Humiliated,” he said. “I would like to get back my British passport so I can go back home.”

As the 70th anniversary passes under a cloud in Britain and Jamaica, the saga still threatens to undermine the historical relationship between the two countries. At a meeting of the Centre for Reparation Research in the Jamaican capital last week, senior Caribbean dignitaries likened the treatment of Windrush victims to a 21st-century version of the Atlantic slave trade.

Sir Hilary Beckles, vice-chancellor of the University of the West Indies, said it was the latest example of Britain’s “project approach” to black people – “you mobilise them for a project and when you’re finished, you demobilise them” – and had far-reaching implications for the Caribbean Commonwealth.

“It is a very deep and severe problem,” he said. “You can read Windrush as a morality tale but it is about the future of black people in the Caribbean. Where next will they want us to labour? Where is the next place they will take us? Why do we not focus on building our own economies and societies? We need to put all hands on deck to get our economies to function at a higher level. That is the only cure to all of this.”