Njideka Akunyili Crosby: The painter in her MacArthur moment

The sidewalk outside Njideka Akunyili Crosby’s art studio in an industrial area south of downtown L.A. is bustling and loud. The other side of her graffiti-scribbled front door, however, is neat and peaceful.

In fact, the room she paints in is completely bare, but for a ladder, fans and a tiny cart housing tubes of paint. Cream and white sheets hang loosely from the window, blocking the sun, and the stark, white walls are studded with nails for hanging works in progress.

Today, there are none. The room is conspicuously devoid of art.

That’s because the Nigerian painter, who has lived in the U.S. for the last 18 years and last month was named a 2017

Propping herself up on a stool to chat, Akunyili Crosby seems somewhat cautious about her success, including the $625,000 award from the MacArthur Foundation. “I’m happy?” she says of this moment in her career. “I’m just so hard on myself, so critical of what I do, that it’s tough to just have that full moment of relaxing and feeling all is well.” She smiles shyly, glimpsing around the spare room. “But, yeah, I’m happy.” Then she breaks into a little contained jig from the waist up: thumbs in the air, forearms gently chugging back and forth. Then just as quickly, she composes herself.

That duality — the diligent artist prone to making lists and putting in seven days a week in her studio versus the goofy creative who might burst into a jig alone in the supermarket aisle — is central to Akunyili Crosby’s identity; hybridity defines her work. She’s a transnational artist who’s lived for roughly equal amounts of time in the U.S. and her native Nigeria, and she’s a career woman juggling a 10-month-old baby. Even her outfit today is a smashup: a worn, cotton T-shirt that says “Native Texan” on it — it belongs to her husband, who is white — worn with blue jeans and a silk scarf she bought in London that is tied around her head in traditional Nigerian fashion.

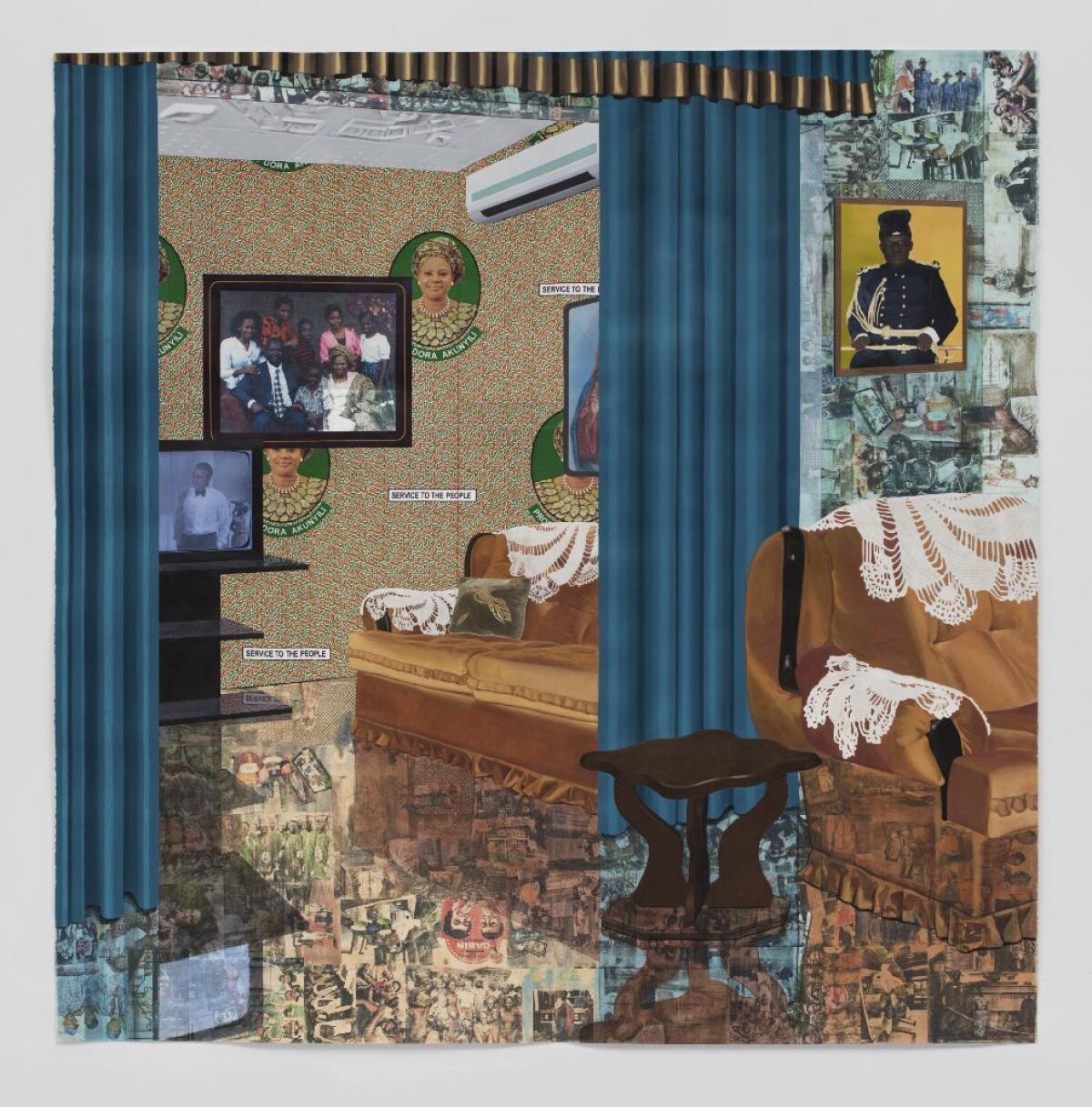

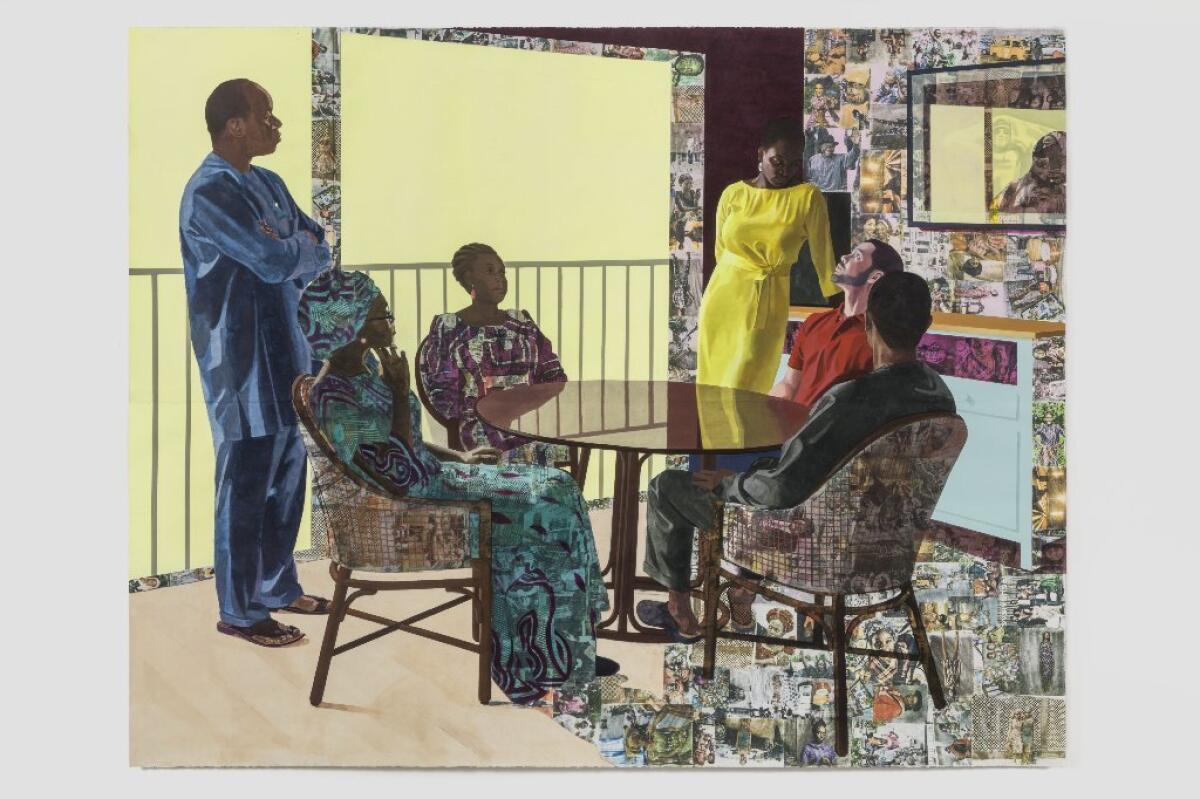

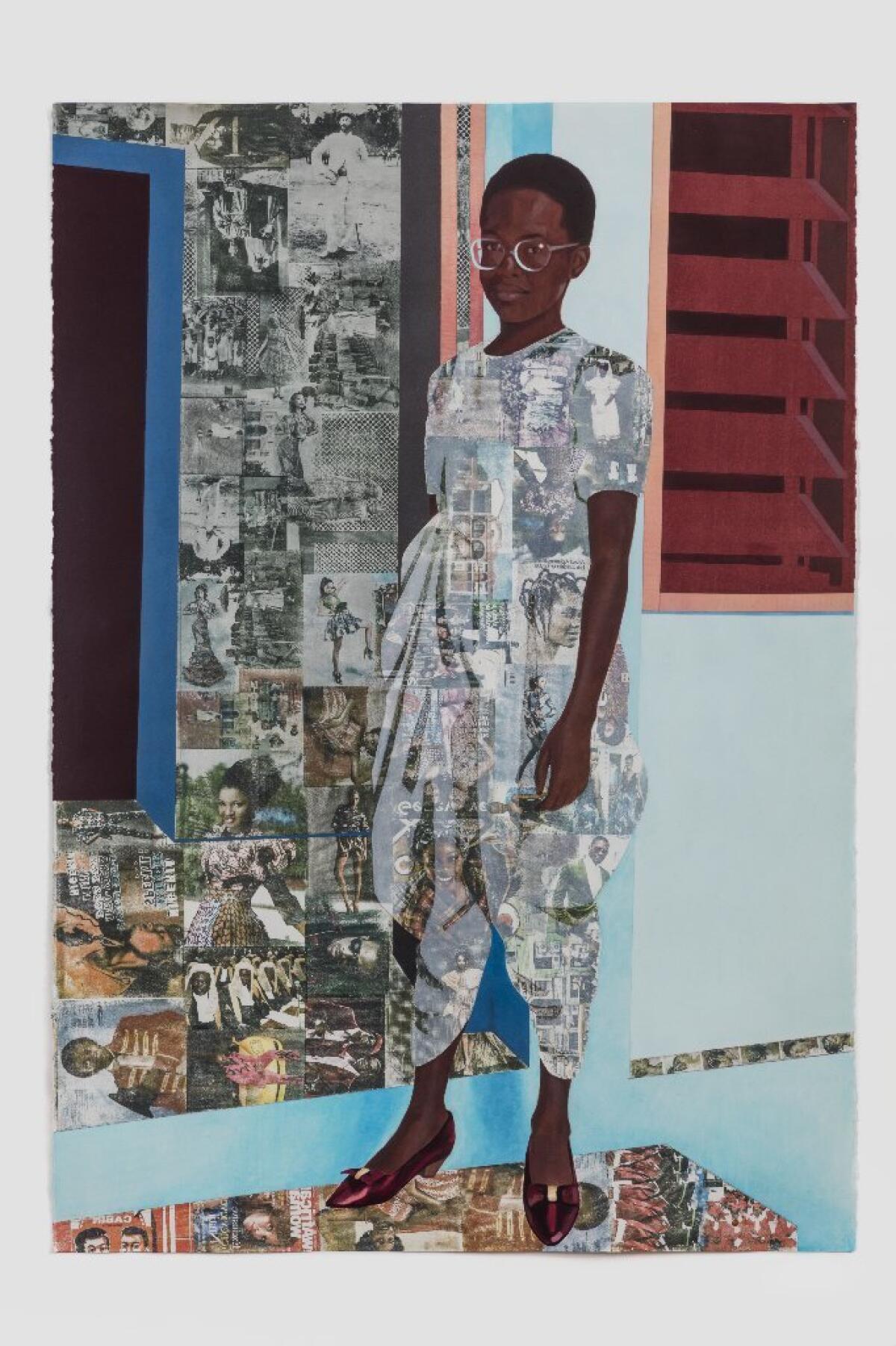

This multinational perspective runs through every one of her pieces. Her large-scale mixed-media works on paper blend figurative painting, drawing, printmaking, photography and collage. The mix of techniques and materials together with imagery from the U.S. and Nigeria — the late dictator Sani Abacha, a friend’s North Dakota wedding, a band in Nigeria that began as Michael Jackson impersonators — speak to straddling nationalities, divided personal histories and the greater appropriation of cultural traditions.

“It really is about what it means to be someone who has existed between multiple worlds and carries all those influences with them at once — for me, a rural Nigerian person, an urban Nigerian person and an American at the same time,” Akunyili Crosby says. “I’m trying to use my work, and my life story, to explore this idea of a liminal space, or a third space, where multiple things come together to yield a new thing.”

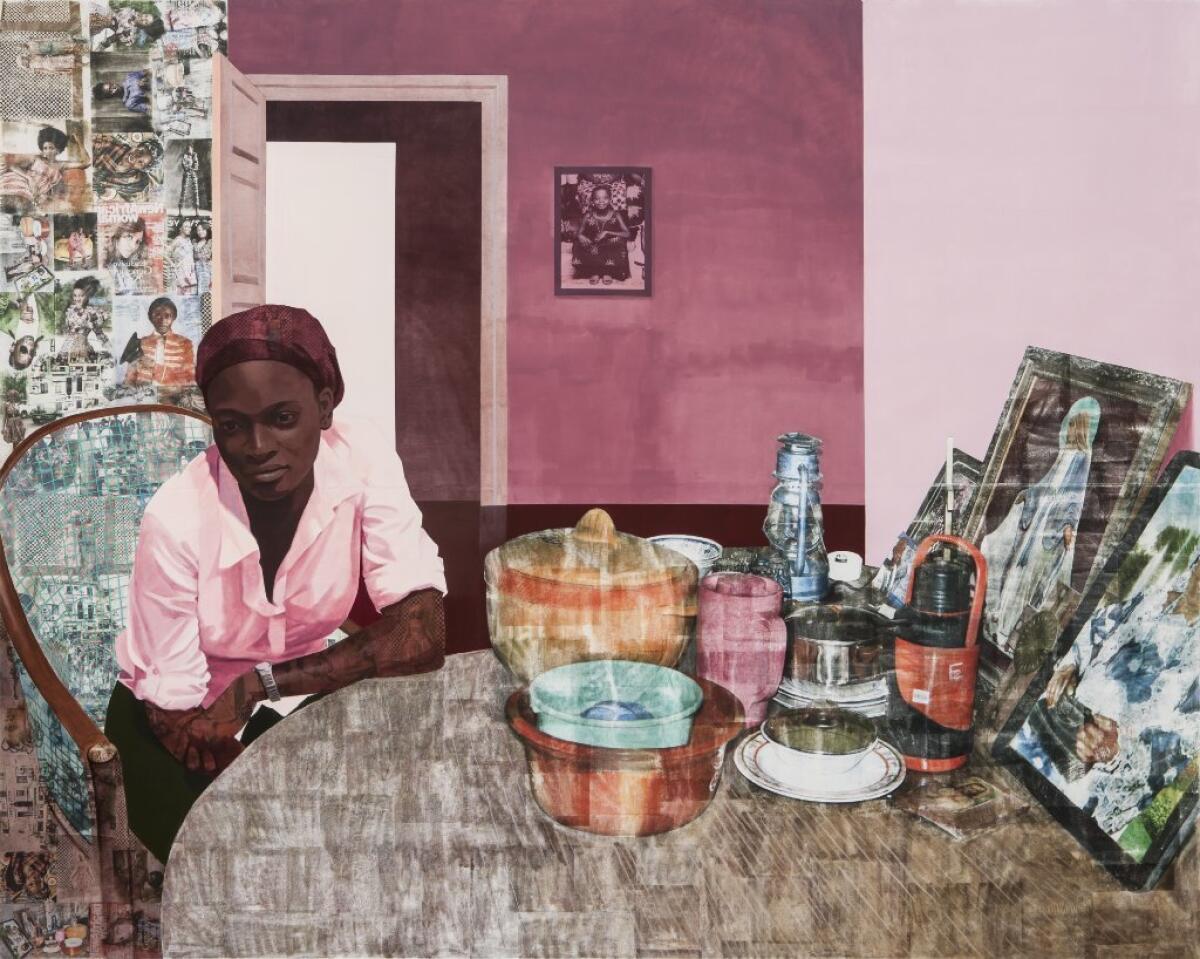

Akunyili Crosby scatters color pictures of her work across a tabletop. Her intimate and seemingly quotidian scenes of domestic life in Nigeria and the U.S. are bold and colorful, literally layered with narratives that are personal and political, “like the layering of sediment,” she says. Into painted scenes of her grandmother’s dining table or her husband hugging, Akunyili Crosby lays dense collages mixing cutouts from Nigerian lifestyle magazines, family photographs, news clippings, album covers and other sources. Occasionally, she glues the images on directly, providing texture, but more often, she photo-transfers them, then applies color washes, which break up the collaged areas into abstract blocks and give them a faded, almost receding effect.

“It’s like a faint, faded memory of a place I used to know, a place I used to live in,” she says.

As personal as they are, the works also speak to cultural appropriation, presenting Nigerian traditions as if Russian nesting dolls. Images of tea service appear repeatedly, a local custom absorbed after British colonialism. She pastes West African portrait fabric into her work, a commemorative cloth worn at celebratory events such as weddings, that’s created using a Dutch wax-print technique that itself originally came from Indonesia.

A pair of works in the Baltimore show each features a self portrait based on near identical photographs. In one, she’s seated at a modest Nigerian dining table; images in the collage below include a photo of her mother from Akunyili Crosby’s wedding, Nollywood actress Genevieve Nnaji and a Nigerian lawyer wearing a traditional white wig. The companion piece depicts the artist seated at an IKEA-like dining table in a West Coast apartment; images in the collage include a photograph of Akunyili Crosby and her husband hiking in Colorado and Janelle Monáe in front of a sign that says, “Black girls rock.”

“Njideka is an artist who has the capacity to really bring together worlds that may not stand in unison. Which is to say the continental African experience and that of black folks living in diaspora,” says Jamillah James, curator at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. In 2015, when James was at the Hammer Museum, she gave Akunyili Crosby her first solo museum exhibition, and she organized a concurrent show of Akunyili Crosby’s work at Mark Bradford’s Leimert Park gallery and social services complex, Art + Practice.

“She’s able to speak universally about the experience of family and community and finding one’s way in the world,” James says. “But there’s something that’s really powerful about putting forth images of black people and having those be embraced by institutions and galleries. I think that’s where the political power of her work really is.”

Growing up in Nigeria, Akunyili Crosby toggled between rural and urban life. Her family lived in Enugu, a former coal mining town, and she spent weekends and summers in her grandmother’s rural village — images of which factor heavily into her paintings. As age 11, she attended boarding school in the more cosmopolitan city of Lagos.

Art wasn’t a large part of Akunyili Crosby’s upbringing. As a girl, she copied pictures from her father’s Time and Newsweek magazines for fun. But hers was a science family: Her father was a physician, and her mother, a Ph.D. in pharmacology, taught and went on to become a government official, heading up the Nigerian version of the Food and Drug Administration. Of her five siblings, three are doctors, a profession Akunyili Crosby always thought she’d end up in.

After her mother won a green card lottery for the family, Akunyili Crosby moved at age 16 to Philadelphia. She took an oil painting class at the local community college, and that sent her on a new path. She studied fine art and biology at Swarthmore College, where she met her future husband, also an artist, and did a stint at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts before earning an MFA in painting from

In the six years since, Akunyili Crosby, now 34, has swiftly ascended in the art world. She was an artist-in-residence at the Studio Museum in Harlem, which honored her with the Joyce Alexander Wein Artist Prize, and she received the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s James Dicke Contemporary Artist Prize, among other awards. In L.A. alone, her work is in the permanent collections of the

Akunyili Crosby reached an entirely new level of recognition when she was named a MacArthur Fellow, recognized for “visualizing the complexities of globalization and transnational identity.”

“I had no idea, none,” she says of winning the award. She was in the car, pulling up to her studio, when the phone rang. “Telemarketers,” she thought, but she picked up anyway. Even after the MacArthur Foundation identified itself, the good news didn’t compute.

“My brain was still playing catch up, I was in a fog,” she says. “I wasn’t screaming and laughing. I just was in a daze, sitting in my car, wondering if I was having a real experience or a dream and hallucination.”

The MacArthur award was something she’d always hoped would come, maybe in her 50s or 60s, “but it was at the end of my list of hopes and dreams,” she says, breathy, as if still stunned by the news. “I’m just excited to hibernate in my studio and experiment.”

That could take a while. Akunyili Crosby works slowly and deliberately, scouring the internet for days at a time, thumbing through family photo albums, reading novels and postcolonial theory, sketching ideas — and it all goes up on a messy process wall. She creates eight or nine large-scale works a year.

Pushing the boundaries of painting — “breaking the rules,” she says — is as important to her as the work itself.

“I’m really trying to figure out how I can work within traditional figurative painting but also, what’s the new thing you’re adding to this conversation?” she says.

The five pieces at the Baltimore Museum of Art, per Akunyili Crosby’s instructions, hang unframed, without glass. The exposed works have movement and texture, says exhibition curator Kristen Hileman.

“It’s like you’re standing in front of huge pages out of a book, or a huge photo album,” Hileman adds. “It’s a very immediate experience of being with the artwork. You get a sense of it coming off the wall, of it coming into your space. The figures in the image are almost life-sized, so you really feel like you’re in the same space as the image.”

The MacArthur “genius grant” is a no-strings-attached award. Akunyili Crosby plans to use the money to travel to Nigeria for an extended period to do research. “I want to go deeper,” she says.

That goes for studio experimentation as well. Other than being included in a group exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery in London in June 2018, no new shows are in the works, giving her some free-form studio time.

“I’m looking forward to having a stretch of time where I’m making work without the pressure of a show and I can just experiment,” she says. “Because it’s in those moments of experimentation that I expand on my practice and discover new moves.”

The end goal? Fill up her studio again with new works.

Follow me on Twitter: @debvankin

ALSO

Sexual harassment allegations at Artforum

Yayoi Kusama at the Broad: Lots of mirrors, not so much artistic reflection

Alejandro Iñárritu's virtual reality installation, 'Carne y Arena,' wins a special Oscar

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.