'There can be no two opinions about the tone in which Dr Leavis deals with Sir Charles. It is a bad tone, an impermissible tone." Lionel Trilling's magisterial judgment expressed a very widely held view. Both at the time and since, FR Leavis's lecture critiquing of CP Snow's "The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution" was and has remained a byword for excess – too personal, too dismissive, too rude, too Leavis. Whatever view they have taken of the limitations and confusions of Snow's original contentions – and Trilling, among others, itemised a good many – commentators on this celebrated or notorious "exchange" (if it can be called that: there was little real give and even less take) have largely concurred in finding the style and address of Leavis's scathing criticism to be self-defeating. Aldous Huxley denounced it as "violent and ill-mannered", disfigured by its "one-track moralistic literarism". Even reviewers sympathetic to some of Leavis's criticisms recoiled: "Here is pure hysteria."

"It will be a classic" was Leavis's own, surprisingly confident, judgment on his lecture. Though few of its early readers concurred – the lecture was more commonly seen as a classic example of intemperate abuse – with the passage of time the merits of its criticisms of Snow and what Snow represented have started to become better appreciated. Now, half a century after its initial delivery (as the Richmond lecture at Downing College Cambridge in 1962), it is appropriate to consider whether Leavis's lecture should indeed be seen as a minor classic of cultural criticism – a still-pertinent illustration both of the obstacles faced by the critic who understands himself to be challenging a set of attitudes that are so widely shared and so deeply rooted as to seem to most members of that society to be self-evident truths, and of the discursive tactics and rhetorical resources appropriate to this task.

Despite criticism that this was an unpardonably personal attack, Leavis always insisted that he was concerned with something much larger than the merits or failings of one individual. And although the episode is usually referred to as "the two cultures controversy", Leavis also insisted that he was not primarily offering a commentary on the disciplinary character and claims of the humanities as opposed to the sciences, still less asserting the educational or institutional priority of one over the other, and most certainly not denying the huge importance of science in the modern world. His real target wasthe dynamics of reputation and public debate – the ways in which certain figures are consecrated as bearers of cultural authority. (Leavis believed there was a lack of an effective "educated public" in contemporary Britain. The facile, vogueish treatment of literary and cultural matters in the Sunday papers and smart weeklies demonstrated the point. In this croneyish, self-promoting world, no serious critical standards were in play, as they could not be, he maintained, where there was no public capable of making true discriminations of quality effective.) But, beyond that, his target was, centrally, the axiomatic status accorded to economic prosperity as the exclusive or overriding goal of all social action and policy. Fifty years later, this can hardly be said to have diminished.

Although the idea of "the two cultures", or perhaps just the phrase itself, may seem to have entered the bloodstream of modern culture, the circumstances under which it was launched on its global career may now, for most readers, require historical recovery and reconstruction. "The two cultures and the scientific revolution" was delivered as the Rede lecture at Cambridge University in May 1959. The two cultures of the title were those of the natural scientists and of what Snow sometimes referred to as "the literary intellectuals", sometimes as "the traditional culture". Snow was taken to speak with authority on both cultures, having begun his career as a research scientist in the Cavendish laboratory at Cambridge (and subsequently played an important role in recruiting scientists into the civil service), but having latterly become best known as a novelist. The core of his argument was that the application of science and technology, and the prosperity that was presumed to follow, offered the best hope for meeting mankind's fundamental needs, but that this goal was being frustrated by the gulf of ignorance between the two cultures and the educational arrangements that, especially in the UK, perpetuated this divide. Snow made clear that he believed the literary intellectuals, representatives of the traditional culture, were largely to blame for this deplorable situation: while the scientists had "the future in their bones", the literary intellectuals were "natural Luddites".

In its published form, the Rede lecture provoked a great deal of discussion, both in Britain and elsewhere, and its success confirmed Snow in his role as a sage and pundit. (Such was his standing in the early 1960s that he was invited by Harold Wilson to become a minister in the newly created Ministry of Technology following the 1964 election, despite never having held any elected office or other political position.) It was these matters of reputation – Snow's standing as a cultural authority as much as the content of his claims – that Leavis was to address in his notorious lecture.

"If confidence in oneself as a master-mind, qualified by capacity, insight and knowledge to pronounce authoritatively on the frightening problems of our civilisation, is genius, then there can be no doubt about Sir Charles Snow's." It is, by any measure, an arresting opening sentence. It immediately announces that Snow's claim to speak with authority is the question at issue. And at the same time it begins the process of undermining that claim by implying that it rests on little more than self-ascribed status born out of a soaring belief in his own capacities. The choice of "genius" as the pivotal word of the sentence is deadly, as is the related use of "master-mind". The rest of the first paragraph reinforces the implied judgment that it is only because Snow holds an exalted view of his own talents that he has been accorded such deferential attention. "Of course, anyone who offers to speak with inwardness and authority on both science and literature will be conscious of more than ordinary powers …" But Snow writes as though he has no doubts on these matters, and it is to the tone of Snow's pronouncements that Leavis addresses one of the most withering sentences in a relentlessly withering performance: "The peculiar quality of Snow's assurance expresses itself in a pervasive tone; a tone of which one can say that, while only genius could justify it, one cannot readily think of genius adopting it."

Although at this point we are only four sentences into the Richmond lecture, a tone quite unlike Snow's is already in evidence – sardonic yet also angry, sceptical yet unyielding. Tone is the home turf of the literary critic, and Leavis's analysis is laced with acute and apt brief characterisations of Snow's style, "with its show of giving us the easily controlled spontaneity of the great man's talk" – a telling description which already begins to expose the sham of the "show".

Leavis set out to challenge and correct this over-estimation of Snow as a sage. "Snow is in fact portentously ignorant"; "Snow exposes complacently a complete ignorance"; "he is as intellectually undistinguished as it is possible to be"; and more in similar vein (we are not yet at the end of the second page). The significance of Snow lies, according to Leavis, precisely in what his unmerited elevation tells us about the society which has accorded him such standing. Leavis is only turning, belatedly and reluctantly, to an examination of the Rede lecture because it quickly "took on the standing of a classic" (even here he is unwilling to collude with the process by saying it "became" a classic). The fact that school-teachers were making their university scholarship candidates read it seems to have been the final straw, given the hopes Leavis invested in recruiting the brightest products of the country's sixth-forms.

The first leg to be kicked away has to be Snow's standing as a novelist; this, after all, underwrites his unique position as one fitted to speak with equal authority on literature as well as on science. Leavis is unsparing: "Snow is, of course, a – no, I can't say that; he isn't; Snow thinks of himself as a novelist." Retaining the cadence of the speaking voice in print can be hazardous, but here the arrest in the middle of the sentence enacts the questioning of the received description. Snow has published books classified as novels, but how far, when judged by the standards of the great practitioners of the genre, does he really have the root of the matter in him? Leavis's answer is offensively extreme: "as a novelist he doesn't exist; he doesn't begin to exist. He can't be said to know what a novel is." In truth, the failings in Snow's novels that Leavis goes on to itemise would probably now be acknowledged by most critics: he "tells" rather than "shows"; much of his dialogue is almost literally unspeakable; his characters are wooden and stereotypical; and so on. Nonetheless, to say of an author who had by this point sold many thousands of copies that "as a novelist he doesn't exist" smacks of shock tactics, as indeed it was intended to do.

Kicking away the other leg from under Snow's standing, that of being a highly-qualified scientist, might seem to have been a more difficult task for Leavis, as a literary critic, to accomplish. But he does not hesitate. Having observed, again with some justice, that there is no sign in the novels that Snow "has really been a scientist, that science as such has ever, in any important inward way, existed for him", he goes on to insist that it is equally absent from the Rede lecture. "Of qualities that one might set to the credit of a scientific training there are none." In their place all we get is "a show of knowledgeableness". It's a severe, even haughty, phrase, but any reader of Snow's essays and journalism is likely to recognise some truth in it. His title to the role of science's champion has been further undermined by the fuller biographical picture of Snow's early career that has emerged since his death, which has underscored that his period as a practising scientist had been relatively brief and not uniformly successful; his turn to other careers may not have been quite as freely chosen as he later liked to imply.

As Leavis proceeds with his indictment, turning next to Snow's loose use of the category of "culture", he makes a observation in passing with significance for the whole activity of cultural criticism. He allows that in the matters under discussion "thought … doesn't admit of control by strict definition of the key terms", and then goes on: "but the more fully one realises this the more aware will one be of the need to cultivate a vigilant responsibility in using them, and an alert consciousness of any changes of force they may incur as the argument passes from context to context". This may seem the merest common sense, a maxim of critical hygiene, but for Leavis it also signals an important tactical principle. Stipulative definition of abstract terms is of very little value – indeed it may get in the way of deeper thinking; instead, the cultural critic cultivates and, by example and even by irritating obstructiveness, incites others to cultivate, a restless dissatisfaction with abstract terms, a mindful awareness of the reductive or Procrustean potential of all general formulations. This is, or should be, home territory for the literary critic, and points to a distinctive role in public debate – a more than ordinary attentiveness to how language functions, not as a distracting fastidiousness, but as the active embodiment of positive values and the only way such values can be made effective in controversy. It is as part of this engagement that Leavis describes the Rede lecture as "a document for the study of cliche".

Cliche results from repetition, and a proposition that is repeated frequently and generally enough acquires the status of the self-evident. Leavis suggests that Snow is a "portent", and thus merits examination, precisely because he is so unoriginal. Snow utters his platitudes with such self-confidence in part because they seem, to him and to many of his readers, to be so obviously true. These are what Leavis calls "currency values", the verbal coin that is rubbed smooth by being constantly circulated in a particular social world. He sees this as almost a closed system: to be recognised by this social world as saying something sensible and significant one needs to endorse its currency-values, and the fact of their being so repeatedly endorsed is what confirms them in their status as self-evident truths. Leavis, here and elsewhere in his writings, comes near to the self-dramatising pessimism of "the outsider" who suggests that it is impossible to obtain a hearing for an alternative perspective, so sealed and self-reinforcing is this system. And yet, by the very fact of his critical writing he is tacitly assuming that there is an audience capable of recognising the truth of his critique, so the power of cliche, though great, is not invincible, the system not entirely closed.

The particular piece of Snow's hackneyed wisdom on which Leavis fastens at this point is the assertion that members of the scientific culture "have the future in their bones", together with its companion claim that members of the "traditional culture" are "natural Luddites". From the mid-19th century, the use of this latter metaphor in English public debate involved a special kind of condescension: those so designated are held to be parading their doomed unrealism by refusing to adapt to technological change. By trying to dig in their heels they are merely digging their own graves. In "the real world", economic change happens; there's no point in bleating about it. Literary intellectuals are, according to Snow, "natural Luddites". Bleating about the costs of progress is what they do.

Snow had presented the contrast between the scientific and literary cultures as being in part about different responses to the industrial and technological revolutions. While the natural Luddites merely rail, the scientists get on with the business of improving the material conditions of life. The existence of the individual, Snow had added, expansively, ends in death and may therefore be considered tragic, but progress represents the onward sweep of humanity collectively: as individuals, "each of us dies alone", but "there is social hope". Yet what, Leavis asks pressingly, "is the 'social hope' that transcends, cancels, or makes indifferent the inescapable tragic condition of each individual?" Where is such "hope" to be found except in the lives lived by particular persons?

The target is the implicit assumption that a social goal could be specified in aggregate terms, such as measures of a rising standard of living, without asking about the quality of the individual experiences that such measures presume to aggregate. Leavis's language at this point is almost a direct echo of Ruskin's famous maxim, used as part of a similar argument (against political economy in his case): "there is no wealth but life". In resorting to such language, Leavis and Ruskin (and others) come up against one of the recurring internal contradictions of cultural criticism: quantitative or instrumental descriptions of the goals of life need to be shown up as inadequate and reductive, yet the character of the alternative ends up being merely gestured to by unsatisfactory phrases about "life".

Leavis's preferred strategy is to suggest that although an adequate characterisation of the goals of human life cannot, without descending into vacuous abstraction, be given in propositional form, great novels can embody such a vision. They ask the question: "What for? What ultimately for? What ultimately do men live by?" Leavis immediately and pre-emptively rules that "Of course to such questions there can't be, in any ordinary sense of the word, answers." In their place, and simply as a shorthand description of a more adequate conception of human life, Leavis points to the work of some of his cherished novelists, such as Conrad and, in particular, DH Lawrence.

In contesting Snow's benignly optimistic interpretation of the consequences of the industrial revolution, Leavis is simultaneously pulling rank on Snow by casting him in the role of superficial philistine, and bumping up against the limits of what cultural criticism can do by way of presenting a more adequate picture of human fulfilment. It is by no means the case that all the leading cultural critics of the past century or more have been literary critics by primary profession, but the high frequency of the overlap is clearly not just a matter of chance or contingent social circumstance. Leavis may be expressing himself with distinctive pungency when he says of Snow's statements about the goal of more "jam tomorrow": "The callously ugly insensitiveness of the mode of expression is wholly significant." But in general the use of more nuanced and delicately inflected language to show up the weaknesses of crass or formulaic writing is the stock-in-trade of the cultural critic.

Perhaps few if any readers, then or now, would consider that all parts of Leavis's analysis were equally well-judged. But while his tactics may occasionally have misfired or been disproportionate, his strategy is worth reflecting on, since it was a bold attempt to confront some of the enduring challenges and dilemmas of cultural criticism.

The first of these is how to find both a platform and a mode of expression that will ensure that views which are dissident or critical of widely-shared assumptions get a proper hearing. Let us suppose that Leavis had brought out a carefully-detailed analysis of Snow's fiction or his educational views in a strictly scholarly journal; some readers may feel that these would have been more practical – or, in the current weasel phrase, "more helpful" – responses, but there can be no doubt that they would have received far less attention. Moreover, the cautious statement of limited disagreements with Snow would, far from calling his standing as a sage into question, have indirectly reinforced that standing. In such cases, it is the whole mechanism by which celebrity is transmuted into authority that needs to be exposed. It is hard to see how this can be done without giving offence to those who themselves have colluded with or been the beneficiaries of that process. And if it is not simply one or other particular view that requires to be criticised, but the poverty of mind that finds expression in such inadequate views more generally, then there may be no more telling mode than astringent literary criticism. Such critical tactics always risk seeming condescending or sneering, but that may be a risk the cultural critic has to take if the systemic limitations of the perspective under examination are to be properly exposed.

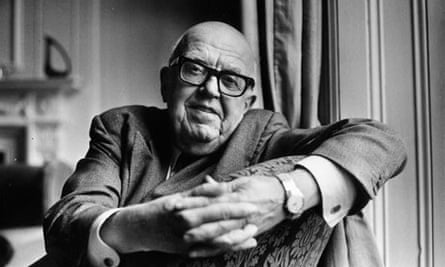

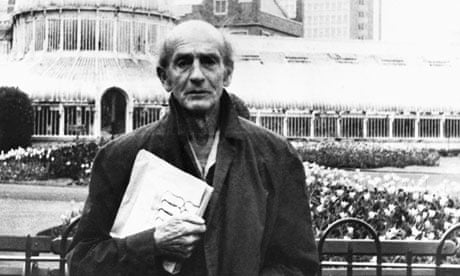

There may be no way of assessing whether Leavis's critique affected Snow's standing and cultural authority. Indeed, it could be said that since the apogee of Snow's public career – his brief spell as a minister in Wilson's government – came soon after Leavis's attack, he cannot have done any significant damage. On the other hand, Snow himself, an inveterate gong-hunter with no low estimation of his own achievements, seems to have believed that the assault jeopardised his chances of the Nobel prize for literature. He certainly remained in demand as a public speaker and commentator throughout the 1960s, though sales of his novels began to fall off. It is probably fair to say that the reputations of both Snow and Leavis dipped in their final years and declined immediately after their deaths (in 1980 and 1978 respectively). While Snow's has never revived, there has been in recent years a substantial amount of serious interest in Leavis's work, including his late forays into public debate.

The attempt to articulate, in such a forum, an alternative to reductive instrumentalism involves a familiar tension or paradox. Most forms of public debate demand brevity and punchiness, but brevity and punchiness encourage reductivism. The critic of treating increased economic prosperity as the overriding goal will always, in effect, be asking what, in turn, prosperity itself is good for. But that is to set oneself up to give some description of the ends of life. "What for – what ultimately for? What, ultimately, do men live by?" A parade of abstract nouns has limited value as an answer. Implying an alternative vision, infiltrating it into the critique of one's opponent's language, may be the only strategy for avoiding such vacuity. There is rarely any shortage of suitable targets. The leaden, cliche-ridden, over-abstraction of so many official documents; the slack, fashion-driven chatter of so much journalism; the meaningless hype of almost all advertising and marketing; the coercive tendentiousness of all that worldly-wise, at-the-end-of-the-day, pronouncing – against these formidable social forces the critic goes into battle armed with little more than a closer attentiveness to the ways words mean and mislead, express truths and obstruct communication, stir the imagination and anaesthetise the mind.

But perhaps we should recognise that the very process of such criticism is the alternative to brisk, explicit statement. Or maybe what is needed, by analogy with the "slow food" movement, is acknowledgment of the role of "slow criticism", which, by its indirection and arrest, causes readers to lose their habitually confident footing and to stumble into more probing or reflective thinking. This does not entirely liberate the critic from the discursively awkward position of appearing to speak on behalf of the ineffable. But by drawing attention to the critical engagement itself, it starts the insidious process by which a prevailing discourse comes to seem shallow or misleading or in some other way inadequate.

From one point of view, Leavis might not seem an obvious recruit to any putative "slow criticism" movement. As he himself wryly notes, one Italian periodical described him as "puritano frenetico", and the intense, combative address of his printed voice does not at first conjure up the process by which the patient accretion of alternative descriptions, almost geological in the pace of its operation, modifies existing sensibilities. Anger operates at a faster tempo, and the Richmond lecture is a deeply angry performance. But closer familiarity with his much-remarked upon syntax suggests that it should be seen as, precisely, a straining against the limits of sequential exposition in the interests of recognising the simultaneity and inter-relatedness of considerations that are flattened by others into blandly self-contained propositions, which in turn congeal into cliche. To be disturbed into an awareness (however uneasy or resistant) of this process is to start to register the power of his critical voice. In these terms, perhaps Leavis's lecture, whatever its flaws, may still be thought to have a claim on our attention, even if opinion remains divided over whether it should be considered a minor classic of cultural criticism.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion