It is easily arguable that the most significant technique change in athletics was high jumping’s “Fosbury flop”. Dick Fosbury, who has died aged 76, invented the eponymous unconventional way of getting over the bar. In the words of the American coach John Tansley, “he literally turned his event upside down”, but besides the sport, the flop’s impact as a paradigm change was even more remarkable.

For millennia, humans had proceeded over obstacles in their paths one foot at a time. Even as the sport of athletics was refined, high jumpers basically followed the techniques of hurdlers and steeplechasers without considering that they, unlike those runners, did not have to continue to propel themselves forward after their jumps. The early “scissors” technique was essentially a hurdle of the bar; the later techniques, the “straddle” and various rolls, looked the way their names implied. High jumpers preceding Fosbury were tall but strong, like sprinters, in the upper body.

The “flop” – which you can see hints of in the twisting rolls of great jumpers who preceded him, Charlie Dumas, John Thomas or Valeriy Brumel – did not come to Fosbury in a “eureka” moment, but as he tinkered with his traditional technique while still at high school in the early 1960s. He found himself moving his body more and more sideways, until finally he was jumping with his back to the bar, body parallel to the ground, and legs perpendicular to it. As his head and torso went over, he would kick his legs high, landing face up on his shoulders. The jump began to describe a parabola.

Despite his coach’s scepticism, the results were evident, and when a photo in the local paper was captioned “Fosbury Flops Over Bar”, the jump had acquired its name. Finishing second in the 1965 Oregon state championships as a senior, he jumped 6ft 5 ½in, fractionally under two metres.

There were others out there developing their own versions, notably the Canadian Debbie Brill, who, aged 17, won Commonwealth Games gold in 1970 at 17 using the “Brill bend”. Those innovators were aided by a small but significant development: high jumpers had always landed, on their feet or on hands and one foot, in pits of sand or sawdust; during the 60s, mats filled with foam rubber started to replace pits. As Dumas, who in 1956 became the first man to clear 7ft, explained in a 1986 interview, “I couldn’t have mastered [the flop]; I just didn’t have the range of motion. On the other hand, the floppers could never have jumped 7ft 8 or 9in and landed in sawdust pits like we did; they could break their necks.”

At Oregon State University, Fosbury’s college coach tried to switch him back to the “western roll”, but agreed to let him use the flop in his freshman team meets. In 1967, he broke the school record with a 6ft 10in (2.08m) leap; all talk of western rolls disappeared. The next year, he won his first of two national college titles clearing 7ft 2½in, then won the US Olympic trials in Los Angeles. But Olympic officials, afraid the flop would not work in the altitude of Mexico City, where the summer 1968 Games were to be held, scheduled a second trial above sea level. He scraped in as the third of three qualifiers, all clearing 2.20m, but Fosbury having more misses.

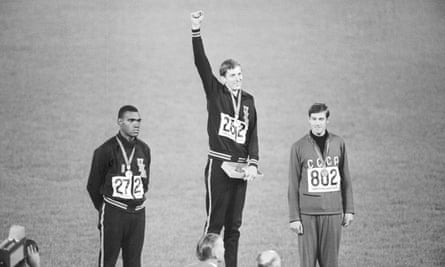

In Mexico City, he won his gold medal, the only jumper to clear an Olympic record 2.24m after a gruelling competition; he failed at three attempts to break Brumel’s world record of 2.28m. The Olympics introduced the Fosbury flop to the world, and showed fellow jumpers film of the style; previously most had seen only photos. By the time Munich staged the games in 1972, 28 of the 40 jumpers were “flopping”.

Born in Portland, Oregon, Fosbury grew up in Medford, where his father, Doug, drove a lumber truck and his mother, Helen (nee Childers), worked as a secretary and was a concert pianist. Fosbury grew tall (6ft 4in) but was not strong, weighing only around 13 stone throughout his career, and had been cut from his high school’s basketball and gridiron teams before finding his way into athletics.

He never equalled his performance in Mexico City and never broke the world record; Brumel’s mark fell to the American Pat Matzdorf, who cleared 2.29m, still using the straddle. But in 1973, Dwight Stones, who had watched Fosbury in Mexico as a 14-year-old, became the first world record-holding flopper at 2.30m, and virtually all jumpers since have flopped. The current world record is 2.45m, set by Cuba’s Javier Sotomayor in 1993.

Following Mexico, Fosbury returned to Oregon State, won his second NCAA title in 1969 and finished his civil engineering degree while competing on the amateur circuit. As more athletic jumpers adopted his technique, he failed to make the US team for the 1972 Munich Olympics. He joined the short-lived professional international track association tour in 1973, then retired and moved to Ketcham, Idaho, and set up a firm specialising in bike and running trails. He became a motivational speaker and author of books such as The Fosbury Flop: A New Philosophy for Success, and Leap of Faith: Overcoming Obstacles and Achieving Success.

He was also a vice-president of the US Olympic Association, served as a county commissioner, and ran unsuccessfully for Congress as a Democrat in conservative Idaho.

In 2008 he was diagnosed with lymphoma in his lower vertebrae; after spinal surgery and chemotherapy, the cancer went into remission. From 2011 to 2019 he served as president of the non-profit World Olympians Association.

With his third wife, Robin Tomasi, whom he met in a swing-dancing class, Fosbury ran a horse farm in Bellevue, Idaho. His first marriage, to Janet Jarvis, and second, to Karen Thomas, both ended in divorce; he is survived by Robin, by a son, Erich, and two stepdaughters, Stephanie and Kristen, from his second marriage, and by a sister, Gail.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion