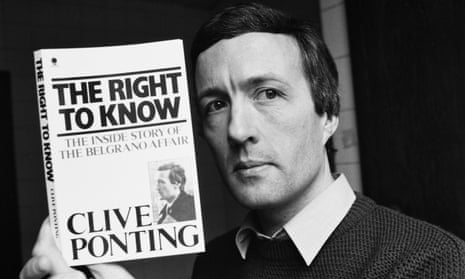

Clive Ponting, who has died aged 74, was a star civil servant who became a whistleblower over the Falklands war. In 1984 he leaked documents about the sinking of the Argentinian cruiser General Belgrano and the following year was sensationally acquitted by a British jury despite his breach of the UK’s then notorious Official Secrets Act.

What has not been disclosed until now is that Ponting also went on to expose one of Britain’s most unsavoury cold war cover-ups – the 1952 attempt to develop bioweapons, during which a trawler off the Hebrides was accidentally doused with plague bacteria. All files on the incident were destroyed, except for a single highly classified folder, which Ponting discovered three decades later, locked in his Ministry of Defence safe.

He confidentially told the Observer about it while I was a journalist on the paper, and in July 1985 the story appeared on the front page with the headline “British germ bomb sprayed trawler”.

Ponting grew up in the anti-authoritarian 1960s. His contempt for the politicians set over him in Whitehall and the Oxbridge types who ran the civil service sprang from his roots in the West Country.

As a high-flyer, his presentation to the prime minister, Margaret Thatcher, of his plans to curb military waste in 1979 was so effective that she asked him to repeat it to the full cabinet, for which he was appointed OBE. She retained an unexpectedly soft spot for Ponting, ensuring that his salary was restored after his arrest in 1984, saying of his treatment: “I think it is a bit rough. He and his family have to live on something.”

Born in Bristol, Clive was the only child of Charles Ponting, who ran a small agricultural supply company, and his wife, Winifred (nee Wadham). He kept up a Bristol grammar school circle of friends all his life. With a first in history from Reading University, he embarked on a PhD at University College London, but abandoned it after two years and in 1970 joined the civil service.

His rise accelerated with the arrival of Thatcher in 1979 and her recruitment from Marks & Spencer of Sir Derek Rayner to wage war on Whitehall waste. Ponting endeared himself to her with a scheme to rationalise food supply for the armed forces, saving £12m on the spot and £3m thereafter.

The OBE followed in 1980, and while only in his 30s Ponting found himself head of a naval department at the defence ministry, with the grade of assistant secretary.

In 1969 he had married Katherine Hannam. After their divorce, in 1973 he married Sally Fletcher, also a rising official at the MoD. They had a Georgian house in Islington, north London, and he enjoyed opera, model trains, fell-walking and cricket. The only two hints he was not of a stereotypical Whitehall species were that he was a discreet founder-member of the short-lived SDP; and that he had a growing interest in Buddhism.

When in 1982 Thatcher sent the navy to recapture the Falkland Islands from Argentina, the Belgrano sinking caused immense controversy. More than 300 sailors, mostly young conscripts, died. The British government maintained that the cruiser had been “closing on elements of our task force” when it was torpedoed.

They stuck to this story against repeated challenge, notably from Tam Dalyell, an aristocratic – and idiosyncratic – Labour MP. The truth was much more nuanced: the cruiser was not in fact sailing towards the British declared “exclusion zone”, and had not been suddenly encountered in the fog of war. It had been shadowed for many hours before the order came down to sink it.

Ponting wrote a secret report dubbed the Crown Jewels for his political masters, the defence secretary, Michael Heseltine, and his junior minister, John Stanley. They rejected his advice that they should be open about the matter when answering parliamentary questions and providing information to a select committee inquiry.

An affronted Ponting sent copies of his documents to Dalyell in the post. He did not bargain for what happened next. Dalyell gave the papers to the committee chairman and Tory MP Sir Anthony Kershaw. He in turn alerted Heseltine, who called in the police. A tell-tale punch-hole led them to Ponting’s office.

In an episode that left him highly embittered, ministry officials offered a deal, that he could confess and resign. He did so. But the politicians stepped in and demanded he be prosecuted regardless. It was then that Ponting showed his mettle. He engaged a fighting civil liberties lawyer, Brian Raymond of the solicitors Bindmans, and pleaded the only loophole that existed in the wording of the Official Secrets Act.

It was permitted to release government information if it was in the “interests of the state” to do so. The judge at the Old Bailey in February 1985, Anthony McCowan, was hostile to this novelty. He told the lawyers, while the jurors were absent, that he might order the jury to convict. The “interests of the state”, he said, were the same thing as the interests of the government of the day.

Journalists at the Observer earned Ponting’s gratitude. They published the courtroom exchanges that Sunday for the jury themselves to read. Like Ponting himself, the jurors did not care to be bullied. They took his side and he was acquitted.

After the cause célèbre of his Old Bailey trial, Ponting made a new career as a revisionist historian with the post of reader at what is now Swansea University, taking aim at such sacred cows as the myth of Britain’s “finest hour” in 1940: Myth and Reality (1990), and Winston Churchill in his 1993 biography.

When he retired in 2004 he moved to a Greek island, but failing health drove him back first to a house in France, then to Kelso in the Scottish Borders, where he signed up with a surprised but pleased Scottish National party.

Towards the end of his life, Ponting’s post-Brexit political views tended to be bleak. He wrote privately in 2018: “I can’t believe what is happening in the world – I suppose we were children of the 60s, but at least there was hope then. And now there’s very little.”

His second marriage ended in divorce, as did his third, to Laura, a teacher. His fourth wife, Diane Johnson, died earlier this year.