Edvard Munch's The Scream is one of the most iconic paintings of the modern era, inspiring silkscreen prints by Andy Warhol, the killer's mask in the 1996 film Scream, and the appearance of an alien race known as The Silence in Doctor Who, among other pop culture tributes. But the canvas is showing alarming signs of degradation. That damage is not the result of exposure to light, but humidity—specifically, from the breath of museum visitors, perhaps as they lean in to take a closer look at the master's brushstrokes. That's the conclusion of a new study in the journal Science Advances by an international team of scientists hailing from Belgium, Italy, the US, and Brazil.

There are actually several versions of The Scream, each unique: two paintings—one painted in 1893, and another version painted around 1910—plus two pastels, a number of lithographic prints, and a handful of drawings and sketches. The inspiration for the painting was a particularly spectacular sunset that the artist witnessed while out for a walk. Munch noted the incident in a January 22, 1892 diary entry:

One evening I was walking along a path, the city was on one side and the fjord below. I felt tired and ill. I stopped and looked out over the fjord—the sun was setting, and the clouds turning blood red. I sensed a scream passing through nature; it seemed to me that I heard the scream. I painted this picture, painted the clouds as actual blood. The color shrieked. This became The Scream.

Some astronomers believe this sunset was likely an after-effect of the 1883 eruption of Mount Krakatoa in Indonesia; reports of similarly intense sunsets were made in several parts of the Western Hemisphere during several months in 1883 and 1884. Other scholars dismiss this notion, arguing that Munch was not known for painting literal renderings of things he had seen. An alternative explanation is that the red skies were the result of nacreous clouds common to that particular latitude. But the spot where Munch most likely witnessed the sunset has been identified: a road overlooking Oslo from the hill of Ekeberg.

The 1893 version of The Scream was stolen from the National Gallery of Norway in Oslo in 1994, where it had been moved to a new gallery as part of the festivities surrounding the 1994 Winter Olympics. (To add insult to injury, the thieves left a note: "Thanks for the poor security.") The gallery refused to pay the ransom, the thieves were eventually caught, and the painting was recovered a few months later.

In 2004, masked gunmen stole the 1910 version of The Scream from the Munch Museum in Oslo, along with Munch's Madonna. Although several men were convicted for the crime, the paintings were not recovered until August 2006. Both had suffered minor damage; the Madonna had several small tears, and The Scream showed signs of moisture damage in the lower right-hand corner.

Even before the robbery, however, the canvas had shown signs of degradation. According to the authors of this latest paper, "Munch experimented with the use of diverse binding media (tempera, oil, and pastel) in mixtures with brilliant and bold synthetic pigments... to make 'colors screaming' by combinations of brightly saturated contrasting colors and variations in the degree of glossiness of their surfaces." But these materials also present a challenge for conservationists, since the materials tend to undergo color changes and structural damage due to photochemical reactions.

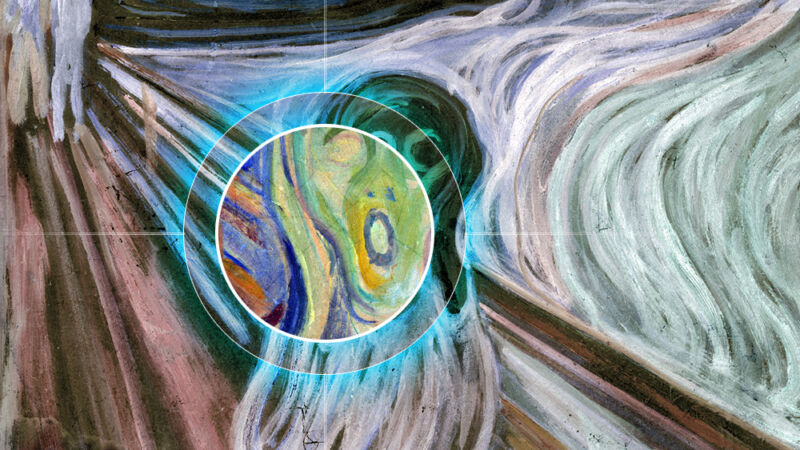

-

Photograph of The Scream (circa 1910), Munch Museum, Oslo; catalogue n. Woll.M.896.Irina Crina Anca Sandu/Eva Storevik Tveit/Munch Museum

-

View of the ESRF, the European Synchrotron, Grenoble, France.ESRF/Stef Candé

-

(From l-r) Annalisa Chieli (University of Perugia, Italy), Letizia Monico (CNR, Italy) and Gert Nuys (University of Antwerp, Belgium) during measurements of cadmium yellow micro-flakes of The Scream (circa 1910).ESRF

In the 1910 version of The Scream, for example, the bright yellow paint in the sunset background and the screaming figure's neck area have shifted to an off-white color, while the thick yellow paint for the lake above the figure's head is flaking off. That's why it's rarely displayed these days, kept safe in a protected storage area with carefully controlled lighting conditions, temperature, and humidity.

In 2010, scientists analyzed the composition of the 1893 and 1910 versions of The Scream and found the pigments used included cadmium yellow, vermillion, ultramarine, and viridian, all common in the 19th century. There have also been multiple studies (using various methods) of degradation of cadmium yellow pigments in particular in paintings by Henri Matisse and Vincent van Gogh. It is Munch's choice of cadmium yellow that poses the biggest challenge, according to the authors of this latest paper.

“It turned out that rather than use pure cadmium sulphide as he should have done, apparently he also used a dirty version, a not very clean version that contained chlorides,” co-author Koen Janssens of the University of Antwerp told The Guardian. “I don’t think it was an intentional use. I think he just bought a not very high level of paint. This is 1910 and at that point the chemical industry producing the chemical pigments is there but it doesn’t mean they have the quality control of today.”

Janssens and his colleagues relied on the ID21 beamline at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) in Grenoble, France, to further examine the paints Munch used. Synchrotron radiation is a thin beam of very high-intensity X-rays generated within a particle accelerator. Electrons are fired into a linear accelerator to boost their speeds and then injected into a storage ring. They zoom through the ring at near-light speed, as a series of magnets bend and focus the electrons. In the process, they give off X-rays, which can then be focused down beamlines. This is useful for analyzing structure because in general, the shorter the wavelength used (and the higher the energy of the light), the finer the details one can image and/or analyze.

"When people breathe, they produce moisture and they exude chlorides."

The scientists conducted luminescence imaging of the canvas to see where the worst paint degradation was occurring. They were able to do so on site at the museum, thanks to a portable mobile spectroscopic platform. Then they used the ESRF beam line to analyze tiny fragments (microflakes) of paint in Munch’s brushstrokes from those regions, as well as an original tube of cadmium yellow he used. They also analyzed samples of artificially aged paint mockups for control purposes.

The results: "The synchrotron micro-analyses allowed us to pinpoint the main reason that made the painting decline, which is moisture," said co-author Letizia Monico of the CNR in Italy. "We also found that the impact of light in the paint is minor. I am very pleased that our study could contribute to preserve this famous masterpiece."

The findings suggest that better control of humidity is the key to preserving the canvas for future generations. “You have to start working with the relative humidity in the museum, or isolate the public from the painting, or painting from the public, let’s say, in a way that the public can appreciate it but they are not breathing on the surface of the painting,” Janssens told The Guardian. "When people breathe, they produce moisture and they exude chlorides, so in general with paintings it is not too good to be close too much to the breath of all the passersby."

That's not an issue at the moment, with museums around the world temporarily closed because of the coronavirus pandemic. But the Munch Museum is scheduled to reopen on June 15, and when it does, Janssens et al. advise future visitors to maintain a safe distance. There is no need to reduce light levels any further, since the study showed that light is not the primary culprit for the degradation. But given the ongoing threat moisture poses, the authors recommended that the museum lower the relative humidity a bit below the current 50 percent. Alas, nothing can be done about the water damage in the painting's bottom-left corner, the result of the robbery.

DOI: Science Advances, 2020. 10.1126/sciadv.aay3514 (About DOIs).

reader comments

38