When the PISA results are released every three years it is now little surprise when a set of east Asian nations (e.g. Singapore, Taiwan, Japan, South Korea) dominate the top spots in the rankings.

These nations typically substantially outperform most English-speaking western nations, with one important exception – Canada.

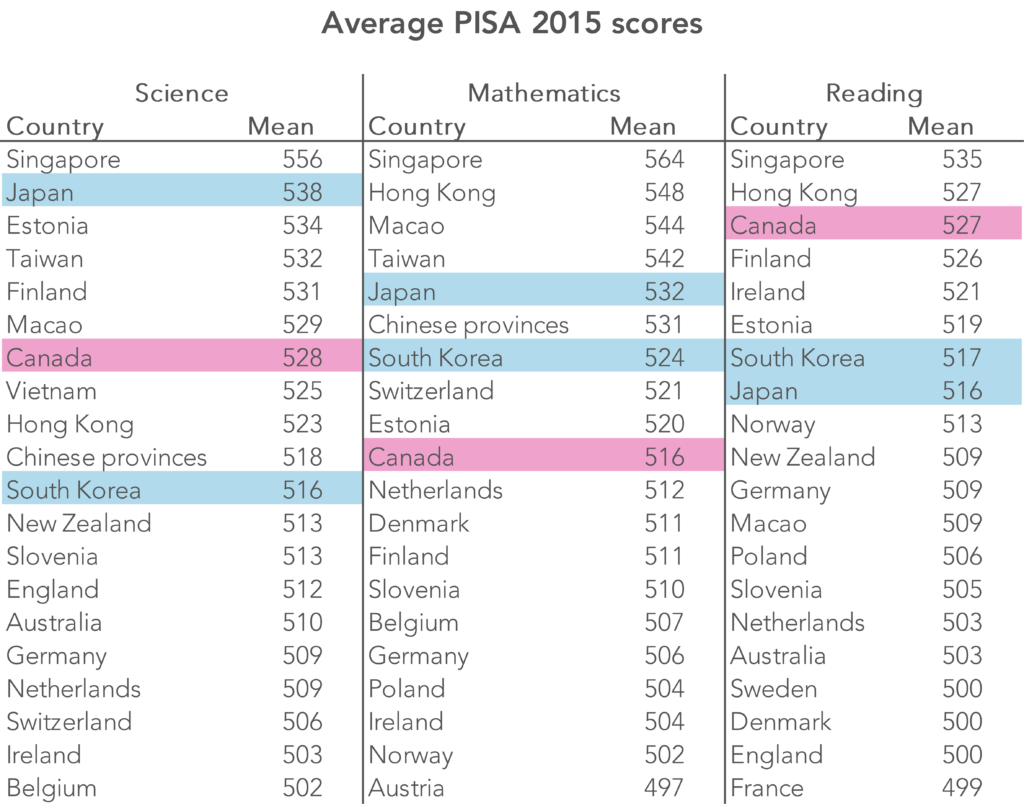

This is illustrated by the table below, which shows the top 20 countries in terms of average scores in reading, science and mathematics.

Canada is the only primarily English-speaking western country that is able to compete with world-leading east Asian nations such as Japan and South Korea.

Source: PISA 2015 national report for England [PDF]

The strong performance of Canada in PISA has not gone unnoticed by policymakers and the education media. Indeed, after the release of the PISA 2015 results, Canada was described as an “education superpower”, with various theories, from the strong academic performance of immigrants through to high levels of student motivation, put forward to explain this result. Andreas Schleicher – the man who has led the OECD’s PISA programme – himself suggested that the strong commitment to equity in Canada is the key.

But how much confidence can we really have in the Canadian PISA results?

One of the key pillars of PISA is meant to be that it is representative of each country’s 15-year-old population.

If this is not achieved, then we are not comparing like with like.

If country A were to disproportionately omit some groups of students (due to exclusions from the PISA sample, non-response or some other reasons) then it cannot be fairly compared to country B where a representative cross-section of young people did actually take part.

The reality is that this is what happens in PISA – and I believe it could substantially undermine the Canadian results.

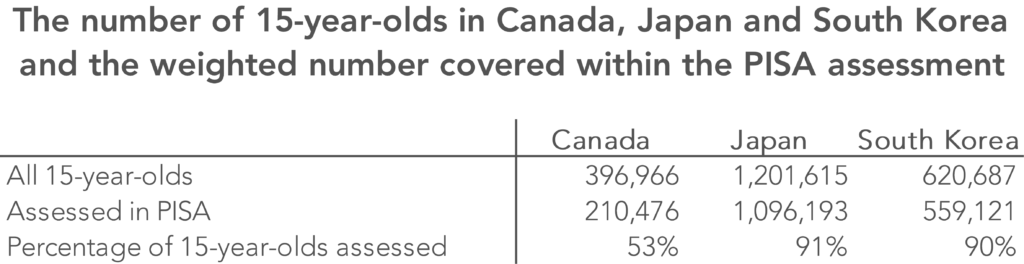

This point is illustrated in the table below, which draws upon figures reported in the PISA 2015 technical report.

The first row documents the total number of 15-year-olds in three large, “high-performing” countries – Canada, Japan and South Korea. The second row provides the number of 15-year-olds that was actually covered within the assessment (weighted to scale the PISA sample up to the size of the PISA population), with the final row giving this as a percentage of the 15-year-old population.

Source: PISA 2015 technical report [PDF]

The figures for Canada are striking. Only around half of 15-year-olds in Canada were covered within the PISA 2015 assessment. This compares to 90% or more of 15-year-olds in Japan and South Korea.

Why do these figures for Canada look so bad? There are a mix of reasons.

First, schools in Canada were more likely to refuse to take part than schools in other countries, with the Canadian national report flagging particular issues within Quebec, where less than half of those schools approached agreeing to take part [PDF].

Second, Canada was much more likely to exclude pupils from taking the PISA assessment for reasons such as special educational needs – a group who are likely to be very low achievers. In total, 7.5% of 15-year-olds were excluded in Canada compared to 2.4% in Japan and less than 1% in South Korea.

Finally, students in Canada were less likely to actually sit the PISA assessment – even within schools that agreed to take part. Specifically, the official figures show that one-in-five Canadian teenagers were counted as absent on the day of the PISA test compared to less than 3% of those in Japan and South Korea.

Together, this adds up to a sizeable problem, which I believe significantly undermines our confidence in the PISA 2015 data for Canada. I believe that there are particular problems in drawing comparisons to other “high-performing” countries – Japan and South Korea in our example – where a genuinely representative cross-section of children took part.

Indeed, after scratching below the surface, evidence of Canada being an “education superpower” does not seem to be particularly strong at all.

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from FFT Education Datalab? Sign up to Datalab’s mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive the team’s half-termly newsletter.

I’d be interested to know the extent to which this analysis would apply to any country on the list. What is the minimum acceptable percentage participation for a country for its data and any conclusions (including ranking) to be seen as valid?

This article is about possiible sampling distortions for Canada compared to the leading PISA ‘East Asian’ countries. I am sure that the author is right that this is an important issue. However as I have have pointed out in my comments to previous articles the high placings of these leading countries disappear when national IQ/cognitive ability data are taken into account. Given that PISA is intended to reflect the effectiveness of national education systems, significant differences in intake cohort IQ/cognitive ability must surely have to be taken into account. These national cohort differences are certainly significant and are discussed in my article.

https://rogertitcombelearningmatters.wordpress.com/2016/12/18/national-iqs-and-pisa-update/

The following country data are alsoconfirmed by GL Assessment CATs ethnicity data for the mean CATs scores of British children of parents of East Asian parents as follows in order of IQ/CATs score, (percentile)

Singapore 109, (73rd)

Hong Kong,China (Tapei, Taiwan,Macau 106 (66th, South Korea 106 (66th), Japan (latest) 105

(63rd)

If my analysis is flawed then someone please point out the error. Readers may not like my conclusions but that is surely not a valid reason for ignoring them.