Houston, We Have a Dragon

The International Space Station and SpaceX’s new capsule for humans are now flying above Earth as one.

CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla.—Believe it or not, getting to space wasn’t the hard part.

In the past few years, SpaceX has mastered launching Falcon 9 rockets and putting payloads into space. The company has also perfected an intricate maneuver that returns rocket boosters to Earth, landing them gently on the ground or on a ship off the Atlantic coast, to be spruced up and used again. Last year, it launched more than 20 rockets into space without incident.

On Saturday morning, a Falcon 9 again soared above Kennedy Space Center, painting a streak of gold against the night sky, and deposited a spacecraft into orbit. After the launch was over, SpaceX engineers braced for the next hurdle. A mistake could put the spacecraft, the International Space Station, or both at risk.

“The ISS still has three people on board, and so this vehicle coming up to the ISS for the first time has to work,” Kirk Shireman, the manager of the ISS program, said in the days leading up to the launch. “It has to work.”

SpaceX manufactured the spacecraft, named Dragon, as part of a NASA program to return human space flight to American soil for the first time since 2011. There were no people on board this mission, only a space-suit-clad mannequin named Ripley, about 400 pounds of cargo, and a plush toy in the shape of Earth, a cute indicator that started to float when the spacecraft reached microgravity. But there could be humans on board as soon as this summer—if the mission goes well.

SpaceX has visited the ISS before. NASA contracts the company to deliver supplies and science experiments on another version of the Dragon spacecraft, designed only for cargo. When those capsules approach, a powerful robotic arm on the station, controlled by an astronaut inside, reaches out to grab them and pull them toward a port.

But the crew-friendly Dragon was designed for a far more complicated rendezvous. The ISS has been preparing for the arrival of a commercially built spacecraft such as Dragon for years. A new docking port was delivered to the station by SpaceX itself in 2016. Astronauts installed new wiring and even rerouted ventilation in this part of the station so that power and air could flow to the spacecraft once it was docked. “It was a massive modification with an incredible amount of hardware,” Susan Freeman, an ISS engineer at NASA’s Johnson Space Center, tweeted on Sunday morning.

The capsule is equipped with software, sensors, and lasers to autonomously guide it toward and then stick itself to a port. Astronauts on the station can transmit important information to the spacecraft’s computers as it nears, but the final docking is up to the Dragon.

After reaching space, the Dragon spacecraft circled the Earth 18 times, firing engines to put itself on a trajectory toward the ISS. When the capsule neared the station, it moved closer and then backed away, practicing a retreat designed for emergencies.

Then, just before 6 a.m ET on Sunday, about 260 miles above the northern coast of New Zealand, the Dragon spacecraft stuck itself onto the ISS. For the first time in nearly eight years, an American-made spacecraft designed to carry humans had arrived at humankind’s home in space.

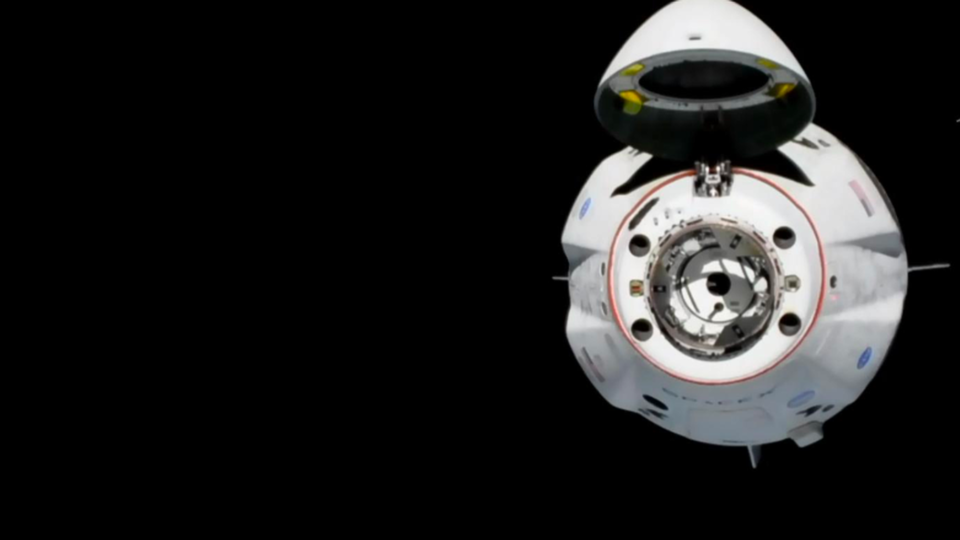

Cameras on the ISS captured the steady approach. At first, Dragon appeared as a white blob against the matte black of space. As the distance between the two spacecraft shrank, the Dragon came into full view, its white exterior gleaming in the sunlight. A cover at the nose of the spaceship had been flipped open not long after launch, revealing a ring of springs. As the Dragon made contact with a port on the ISS, the springs absorbed the impact. On the port, a dozen hooks latched the capsule into place.

Back on Earth, SpaceX headquarters erupted in cheers at the sight. Elon Musk, the company’s founder, no doubt exhaled. The mission has scrambled his nerves. “To be frank, I’m a little emotionally exhausted,” a serious-faced Musk told reporters on Saturday, an hour after the launch. “Because that was super stressful. But it worked—so far. We have to dock with station; we have to come back. But so far, it’s worked.”

Here’s the view from the ISS, at left, and from Dragon, at right:

The @SpaceX Crew Dragon is attached to the @Space_Station! It’s a first for a commercially built & operated spacecraft designed for crew! #LaunchAmerica pic.twitter.com/ddck58TVnP

—NASA Commercial Crew (@Commercial_Crew) March 3, 2019

The ISS crew—Anne McClain of NASA, David Saint-Jacques of the Canadian Space Agency, and Oleg Kononenko of Russia’s Roscosmos—monitored the historic approach. After the Dragon docked, the crew members prepared to go inside. They conducted a series of checks, including an inspection of the airtight seal of the spacecraft and the air pressure inside a vestibule between them. Cameras inside the station showed the crew members floating around a square-shaped hatch, sliding their socked feet under wall railings to anchor themselves when they needed to use their arms.

Two hours later, they were ready. “Houston station, Dragon hatch opened,” McClain said. The scene, captured now on a camera inside the Dragon, was surreal. The astronauts, wearing protective masks, floated about the cabin, inspecting the interior and collecting readings of the environment. It was difficult to say who looked more out of place: Ripley the mannequin in a sleek white-and-black spacesuit, or the crew, in pale-blue polo T-shirts and loose pants.

Astronauts on the @Space_Station have opened the hatch on @SpaceX’s Crew Dragon spacecraft! The station crew can now go inside the first American spacecraft to autonomously dock to the orbiting laboratory. 🇺🇸 pic.twitter.com/z2rP5MWCqu

—NASA Commercial Crew (@Commercial_Crew) March 3, 2019

Only later, once their technical work was done, would the astronauts dress up in blue jumpsuits of their own for a more formal welcome ceremony. They floated into the capsule again, where McClain held up the plush Earth to the camera.

Before the launch, Russia seemed hesitant about SpaceX’s unprecedented maneuver. Roscosmos, which controls half of ISS, was concerned about the capsule’s docking software, which diverged from what other spacecraft have used to rendezvous with the station. NASA officials believed the software configuration was safe and wanted to move forward. It was an uncomfortable moment between the two nations, but just days before lift-off, Roscosmos gave its approval for the launch.

After the Dragon spacecraft’s seamless docking, Roscosmos offered a rather passive-aggressive message of congratulations on Twitter. It commended NASA, but left out SpaceX, and added that flight safety must be impeccable.

The snub likely comes from the top. Dmitry Rogozin, the head of Roscosmos, doesn’t seem to be a fan of Musk. Last month, Rogozin told Russian media that he doesn’t believe SpaceX can build better rocket engines than Russia can. “Musk is not a technical expert in this matter,” Rogozin said. “He just doesn’t understand what this is about.” Musk responded on Twitter, pointing out that “I have been chief engineer/designer at SpaceX from day 1.”

For Musk, the docking speaks for itself. But the mission isn’t over yet. The Dragon spacecraft will spend the week at the ISS. The crew will eventually replace the new supplies with cargo destined for home. The hatch will be sealed up, and the spacecraft will prepare for more high-stakes maneuvers, including a fiery plunge through Earth’s atmosphere and a gentle parachute ride to the Atlantic Ocean.

If the Dragon returns home in one piece, SpaceX and NASA will spend weeks reviewing data and completing more tests. Ripley’s ride will be over, but another journey—far more thrilling and nerve-racking—may follow.