This blogpost reports findings from Nuffield Foundation-funded research conducted into teacher health and wellbeing.

Even before the Covid-19 pandemic hit, there was much discussion about teacher wellbeing and mental health. It was often argued that the stress of teaching was a key factor driving many out of the profession, leading to the teacher recruitment and retention crisis that has affected the sector over the last few years.

More generally, there is a narrative that seems to have emerged that teachers are in worse mental health, and have lower levels of wellbeing, than individuals working in other professions. Stories in the media have emerged about the stress of teaching, and about how choosing to work in this profession is bad for your mental health.

But is this really true? Let’s take a look at the evidence.

How does the wellbeing of teachers compare to that of other professions?

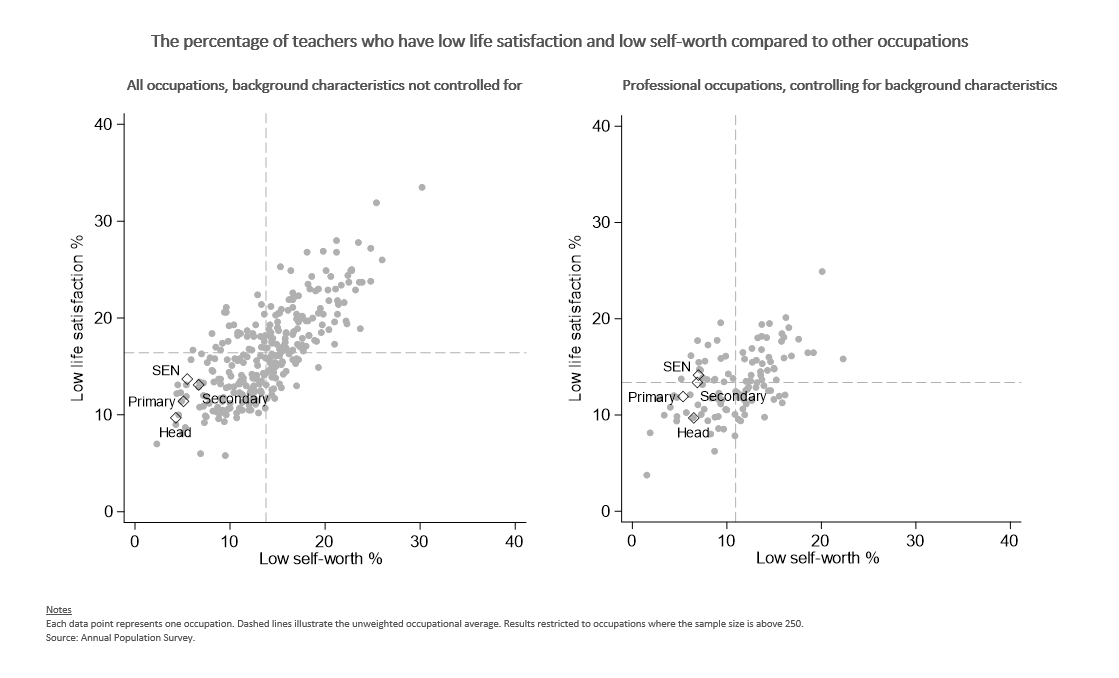

In a recent paper, I used the Annual Population Survey along with several other data sources to compare the wellbeing of teachers to that of other occupational groups (e.g. nurses, accountants, civil servants, graphic designers). A comparison of the percentage of workers in each occupation who were unhappy in life (horizontal axis) and who had a high levels of anxiety (vertical axis) is presented in the charts below.

The chart on the left suggests that each of the four groups of teachers looked at (primary, secondary, SEN and headteachers) have similar or lower levels of unhappiness when compared to other occupational groups. Indeed, levels of unhappiness are particularly low among headteachers – who are one of the happiest occupational groups.

Still sticking with the chart on the left, results for anxiety levels are, however, rather different. All four groups of teachers sit above the dashed horizontal grey line: they have anxiety levels above the average for all occupations.

But this analysis does not account for the background characteristics (e.g. age, gender, marital status, education level) of individuals working in different jobs.

That is what the chart on the right does – as well as restricting things to just professional occupations, such as graphic designers, solicitors and civil servants.

When we control for background characteristics and narrow the focus in this way, this previous results disappear. In fact, primary, secondary and SEN teachers are all in the centre of the graph, with anxiety and unhappiness levels around the average for those working in professional jobs. (Headteachers have slightly higher levels of anxiety, but lower levels of unhappiness).

The next pair of charts presents analogous results for two other dimensions of wellbeing – self-worth and life satisfaction. Note that these measures are defined in terms of low self-worth and low life satisfaction – so the lower the percentage the better.

This paints a similar picture. Teachers on average have no worse – and, in terms of self-worth, slightly better – levels of wellbeing than other professionals.

Other pieces of evidence

Now, one could argue that the Annual Population Survey is just one dataset, and these are just four specific measures. Hence, in a recent paper with colleagues, we repeated this analysis across a total of 11 datasets. These include a range of different measures, including prescription of antidepressant medications and a wide array of standardised mental health and wellbeing scales widely used in academic research.

On the whole, they all point to a similar result. Teachers do not have worse wellbeing and mental health outcomes than similar individuals.

To substantiate this still further, we have replicated these results using objective biomarker measures, and shown that recently qualified teachers do not have worse mental health outcomes than before they joined the profession, and that those who quit teaching for other employment do not see any improvement in their wellbeing overall.

Implications

Why is this important?

Well, for years now, there have been ongoing challenges with the recruitment and retention of teachers in England.

It’s important that appropriate support is available to those who need it, but we should ask whether we can really expect people to decide to become teachers if all they hear about is how wellbeing is low – and rates of mental ill health are chronic – within the profession.

In reality – and despite all the media hype to the contrary – teachers’ mental health does not seem to stand out as especially poor in comparison to other occupational groups. It is high time that this myth gets once and for all dispelled.

The project has been funded by the Nuffield Foundation, but the views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily the Foundation. Visit www.nuffieldfoundation.org.

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from FFT Education Datalab? Sign up to Datalab’s mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive the team’s half-termly newsletter.

Hi there.

I am an experienced teacher and youth worker and have recently completed my masters in the psychology of education at the university of Bristol.

For my research project I chose to investigate an area of personal significance- how lesson observations effectvteacher wellbeing. My argument is that lesson obs can be used for good or bad, either as a developmental tool or a punitive measure which is also open to bias and unreliable.

My findings indicate that lesson obs have a high effect size ob all three aspects of wellbeing: environmental, communal and personal. Furthermore, during stage Two of my research teachers were interviewed regarding this. Experiences ranged from arbitrary feedback to malicious and invalid lesson obs results used to coerce teachers out of the profession- bullying. This is a highly nuanced area of inquiry.

I do agree that in general teachers wellbeing is no different than that of other high-responsibility professions, however there are crucial areas where we can improve teacher to reduce the detrimental effects upon wellbeing.

This was the email reply I received from my London teacher daughter.

“Very interesting. I think if you took away the holidays this would look significantly different! I don’t think i could do it without the regular breaks. But I think all jobs are tough and demanding these days…look at the hours my fiancée and sister do!

I have also noticed since lockdown how regimented teaching is compared to the private sector e.g. you feel guilty for going for lunch for longer than 10 minutes or run to get a coffee as you can’t be gone long. The private sector is a lot more flexible and seems like a more adult world where as teaching seems to be more rules and restrictions outside of the actual parameters of the job”.

I used to work a .5-18hrs teaching contract coupled with a .5-14hrs Learning support contract- 32 paid hours a week. I averaged 65+ hrs a week of work time which I meticulously calculated and averaged over three weeks. That is 33 unpaid hrs for an 18 hr teaching job as I had no extra work to do for learning support. I had no help or support from my management. Looking back this horrified and sickens me. Although no one should have to do such insane amount of work, I do feel pangs of irritation and jealousy of teachers who say they gave a ‘work-life balance’ as I have been conditioned to accept that as “you are not working hard enough”. It is so sad- it dies not need to be this way.