“We have got to fight against privilege,” George Orwell exhorted in 1941, “against the notion that a half-witted public schoolboy is better for command than an intelligent mechanic.” England, he wrote, is governed by an “unteachable” ruling class that too frequently escapes into “stupidity”, failing to see “that an economic system in which land, factories, mines and transport are owned privately and operated solely for profit ... does not work.”

Only a socialist revolution, he continued, could unleash the “native genius of the English people”. Of course, “the bankers and the larger businessmen, the landowners and dividend-drawers, the officials with their prehensile bottoms, will obstruct for all they are worth”. But, never mind: “if the rich squeal audibly, so much the better”.

One measure of how little has changed is that Orwell’s diagnosis of the country he called a “rich man’s paradise” – and even his specific prescriptions: nationalisation of basic industries, abolition of hereditary privilege, educational reform and punitive taxation of offensively unequal incomes – still resonates, almost eight decades later, as the United Kingdom goes to the polls. The long English past of entrenched privilege and extreme inequality is back, if it ever went away. The problems stemming from archaic political and social structures, and an economy geared to further enriching the rich, seem even more intractable.

At the same time, the wartime English patriotism that Orwell tried to alchemise into socialism as highly intelligent Germans tried to kill him has degenerated into self-destructive nihilism during the Tory onslaught on a German-dominated European Union – which countenances even the breakup of the UK.

Fragmentation of the UK would of course leave the Welsh and the Scottish with a sharper sense of their political and cultural identity. Englishness, on the other hand, appears as foggy as ever. As the hunters of an authentic English national identity lurch towards a political climax, it seems worth asking: what is it all about?

Englishness was always a form of theatre, first staged in overseas colonies. Discovering its traces in Rudyard Kipling and India, VS Naipaul remarked on how, “at the height of their power, the British gave the impression of a people at play, a people playing at being English, playing at being English of a certain class”. Today, in a post-imperial Britain run by half-witted public schoolboys, the English character seems even more, as Naipaul wrote, “a creation of fantasy”.

Those such as Orwell, who saw through the fantasy, were usually mortified. He was born in Bihar in India to an opium agent, with a Caribbean slave-owner as an ancestor. While working as a colonial policeman in Burma, he discovered imperialism to be an “evil despotism” and Englishness to be a humiliating act: a pose of masculine authority and racial superiority necessary to keep volatile natives in their place. Others such as Enoch Powell, a lower middle-class native of the West Midlands, were seduced by this posture of stiff-upper-lipped preeminence. Powell became a classicist at Cambridge, taught himself fox-hunting, and wrote highly wrought Georgian verse; he exulted, as a brigadier, in the hierarchies of empire in India. Then, like Curzon, Milner, Cromer and other purveyors of an Englishness made in India and Egypt, he came to develop a certain rather fierce idea of England and its destiny.

Orwell, on the other hand, was an archetype of the unpatriotic leftwinger on his return home – until he found a lodestone of native English genius in the “red wall” of northern England. The spirited English response to Hitler’s vicious assault deepened his conviction of having discovered a new “emotional unity” in England – one that a socialist revolution could turn in favour of its downtrodden people. He persuaded himself that “England, together with the rest of the world, is changing”, and a new middle class blending in with the old working class would bring forth “new blood, new men, new ideas”.

War did indeed awaken a spirit of social egalitarianism, leading to Conservative defeat in 1945. Some of Orwell’s proposals were partially implemented by the Attlee government. Still, there was always something too sanguine about the homecoming scenario of a deracinated intellectual. For, if England was a family, as Orwell claimed, with “rich relations who have to be kowtowed to, and poor relations who are horribly sat upon”, then, as a range of foreign and English observers noted at the time, it was a family marked to an unusual degree by sadomasochistic relationships.

JG Ballard, another disaffected child of imperialism, who arrived in England in 1946 after three years in a Japanese internment camp in Shanghai, was not only appalled by his country’s “grotesque social division”; he also marvelled at the “system of self-delusions” that enabled a people comparable in their poor education, diet and grim housing to the menial toilers of Shanghai to give their lives to “an empire that had never been of the least benefit to them”. “The English class system, which everyone secretly accepted, for reasons I have never understood,” Ballard later wrote, was an “instrument of political control”. Far from collaborating on revolution, the straitened middle class feared and despised the working classes, especially organised labour, and was obsessed with enforcing codes of behaviour that were “calculated to create a sense of overpowering deference”.

As for the upper class, the American critic Edmund Wilson noted in 1945 how its members manifested the “appalling” traits he had found in novels such as Thackeray’s Vanity Fair and Butler’s The Way of All Flesh: “passion for social privilege” and “dependence on inherited advantage”. The great New Zealand memoirist Janet Frame, discussing the seemingly unbreakable social hierarchy of England’s natives with other indigent New Zealanders and Australians in London in the 1950s, concluded: “They’re in the Middle Ages.”

“Change, I felt, was what England desperately needed,” Ballard, reminiscing about the 1940s, wrote two years before his death in 2009, “and I still feel it”. Yet England’s political and social system had long been premised on regulating change when it favoured the middle class, neutralising it when it was demanded by the working class, all the while safeguarding the unteachably stupid upper class. Walter Bagehot, the Economist editor with an acute phobia for England’s poor and disenfranchised, put it frankly in 1867: the unwritten “English constitution in its palpable form is this – the mass of the people yield obedience to the select few”; they “defer to what we may call the theatrical show of society”.

Discussing the role of the monarchy in this show, Bagehot was equally blunt: “We must not let in daylight upon magic.” In other words, the masses of England were to be ruled by almost the same combination of pomp, bluff and repression that the natives of India were. The fossilised politics enjoyed greater legitimacy at home because the English had lived through much of the modern era as its winners, innovating industrially and expanding commercially before other countries; the mystique of British power commanded deference, while perpetuating such archaisms as a single parliament representing four nationalities. Though as exploited and defrauded as Indians, the English people, Orwell wrote, “manifestly tolerated” their selfish, incompetent and often “silly” ruling class; the “post-war development of cheap luxuries” in particular averted revolution.

The Economist reassured itself in 1977: “Britain’s very stability, the beguiling flummery attending its institutions, hold most of its citizens in a trance of acceptance.” But the trance had begun to break after 1945 when, instead of enlarging the realm on which the sun never set, the English began to retreat and, simultaneous with the loss of colonial territories, the colonised started to arrive in a war-ravaged England. Powell, among others, had cherished a starry-eyed notion of the empire as a large multiracial family (with white males on top). But the unstated proviso for the imperialist paterfamilias was always that the dark-skinned family members stay in their respective countries and not seek to live, work and marry white people in England. The new arrivals, prompted by the postwar need for NHS nurses, bus drivers and other workers, quickly exposed this separate-but-equal chicanery of the “Commonwealth”. Writing in 1953 to his wife, Naipaul summed up the hostile environment the British empire’s previously invisible citizens confronted in England. Considered only “for jobs as porters in kitchens, and with the road gangs”, the Oxford-educated Trinidadian had been reduced, he claimed, to a “poor wog, literally starving, and very cold” with “no fire in my room for two days and only tea & toast in my stomach”. “These people want to break my spirit,” Naipaul wrote. “They want me to forget my dignity as a human being.”

The fact that most people from the colonies inhabited even lower depths of poverty, humiliation and despair had little effect on public opinion and policy. Racialised immigration acts were passed throughout the 60s; the poor “wogs” were also repeatedly put in their place by the police, the media and politicians. A Tory candidate in Powell’s own stomping ground, the West Midlands, won his election in 1964 with the campaign slogan: “If you want a nigger for a neighbour, vote Labour.”

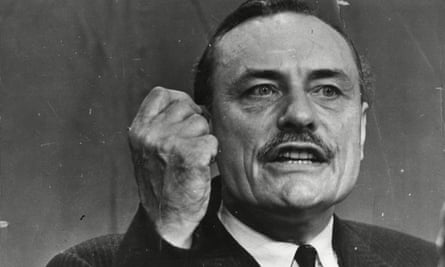

Still, those accustomed to lording it over dark-skinned natives in the outposts of empire could not be appeased. If, as Naipaul wrote, “to be English in India was to be larger than life”, then, to be English in multiracial England after 1945 was to know a devastating loss of manliness. Decolonisation had been outrageous enough for Powell, who had hoped as late as 1951 for Churchill to reconquer his great love, India. The appearance on English streets of dangerous savages against whom Englishness had been defined on the imperial frontier was just too much. The racial hierarchy in which he had forged his self was in danger of recalling the outbreak of virulent prejudice against Jewish immigrants of the period 1890-1905. As he put it in his 1968 “Rivers of Blood” speech (quoting an unnamed, “quite ordinary” person), “in this country in 15 or 20 years time the black man will have the whip hand over the white man”. There was also something intolerable about the fact that imperialism had become, if not a source of shame and embarrassment, then a subject for comedy and satire among a younger generation – summed up by the album cover of the Beatles’ Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Upstart darkies and cheekily androgynous Liverpudlians turned the 1960s into a hellish time for Powell.

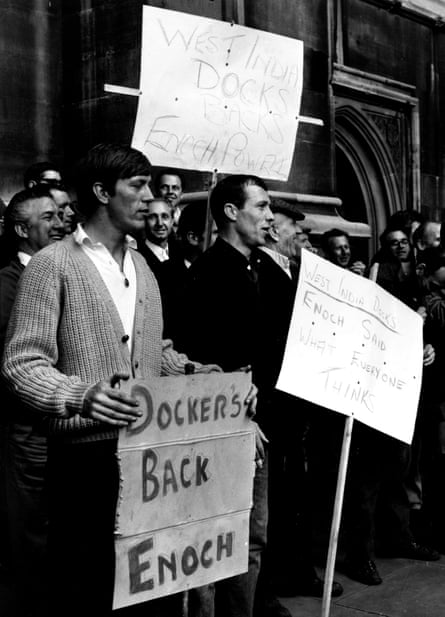

“What sort of people do we think we are?” he thundered in 1967. One self-pitying answer was: a “nation of ditherers”. The following year, Powell mutated into a ventriloquist for the silent majority – members of the white working class who worried about immigration, and were denounced for their honesty as racist, and ignored by “academics, journalists, politicians and parties”. In a classic sleight-of-hand of intellectual demagoguery, the former professor of ancient Greek claimed to be only articulating “plain truths and commonsense” that decent, ordinary people, bullied by a politically correct establishment, did not dare express.

The usual temptation to hold foreigners and immigrants responsible for decline and stagnation was strong in England as postwar economic growth tapered off. In Kamala Markandaya’s outstanding, recently republished novel The Nowhere Man (1972), which is set in the weeks around Powell’s speech in April 1968, a white Londoner reduced to living with his wife’s mother is greatly relieved to discover that black people are to blame for his luckless existence. “A great light bursts upon” him as he receives Powell’s newly respectable wisdom: “They came in hordes, occupied all the houses, filled the hospital beds, and their offspring took all the places in schools.”

Writing in 1970, the journalist Paul Foot pointed out: “all that has changed is that new scapegoats must be found for the homelessness, the bad hospital conditions, and the overcrowded schools”. Political theorist Tom Nairn cautioned, however, against the then common tendency to dismiss Powell as a posh race-baiter, or a moustached blast from the imperial past. Nairn pointed out that Powell, turning his back on an irretrievably lost empire, had set out to construct a post-imperial English nationalism with a mass base. The problem with English identity always was that it consisted of little more than a theatrical performance of brute power abroad by men of the imperial ruling class. It had lacked any broad content at home (notwithstanding Orwell’s infusions of socialism and his belated patriotism). More ambitiously and successfully than Orwell, Powell was now forging a native English genius at home by defining it, initially at least, against emasculating foreigners.

Nairn predicted a long-term future for Powellism, which, he wrote in 1970, “actively stirs up conflict instead of conspiring to stifle or ignore it” and in an existential crisis “can pull the whole of the official structure of British politics in his direction”. In retrospect, Powell himself charted the high English road to Powellism, as he invested his zeal for stark antagonism in Ulster Unionism, neoliberalism and, finally, Europhobia: “Belonging to the common market,” he wrote in 1975, “spells living death, the abandonment of all prospect of national rebirth, the end of any possibility of resurgence.”

¶

A very different destiny for England, which did not involve quacks vending pills for imperial-era virility, was always likely. The possibilities lay in its multi-racial experience – something genuinely new in England since Orwell’s time. Some of the early arrivals were deeply damaged by it, such as Naipaul, who escaped from the humiliations of “wog-hood” into the company of those gratified by his scorn for “wogs”. But many others came to attest to the potential of much more fluid post-imperial identities. “I am an Englishman, born and bred almost,” the protagonist Karim Amir declares in Hanif Kureishi’s The Buddha of Suburbia (1990).

Yet it was, significantly, Powellism that steadily built up to its present political apotheosis in Brexit – through the Thatcher-Blair years of deregulation and privatisation, a hardening political consensus against immigration, a tabloidised culture of journalism and demented Tory EU-baiting, all assisted by the propaganda empire of an Australian media tycoon almost as committed to a politics of xenophobia as his father, a stalwart of Keep Australia White.

Until such time it could hunker down in Westminster, Powell’s hyperbolic Englishness renovated its original home in the realm of kitsch. In Julian Barnes’s England, England, a marketing company desperate to make money out of a country in rapid decay decides to build a theme park of Englishness on the Isle of Wight. A tycoon modelled on Rupert Murdoch and Robert Maxwell persuades the royal family to move to a more up-to-date copy of Buckingham Palace as real England collapses into pre-industrial squalor.

England, England, published a year after Princess Diana died and the Millennium Dome began construction, now seems a timely meditation on the fate of English identity. Englishness had descended deeper into parody throughout the 80s and 90s, as a Sloane Ranger princess let in too much daylight on the magic of the monarchy, and the devolutionary demands of Scotland and Wales uncovered the many faultlines in the notion of Britishness. Many a cultural and intellectual entrepreneur emerged during these decades, ranging from St George flag manufacturers to Churchill fanboys, hectically retailing Englishness, and elaborating Powellism in highbrow as well as lowbrow modes.

Roger Scruton, the philosopher and author of England: An Elegy, took up Powell’s lament about the despoliation of England, giving it a neo-pastoralist orientation. Scruton, who shared Powell’s ancestry in northern England’s lower middle class, reinvented himself as a fox-hunting squire, as prone to defend public schools from his own Labour-voting father’s “resentment” as to sneer at the people who “litter the country with their illegitimate, uncared for and state-subsidised offspring”. As Tory-New Labour free-marketeering eviscerated traditional communities and social bonds, Scruton chose to deplore the loss of the stiff upper lip that “went with imperial pride”.

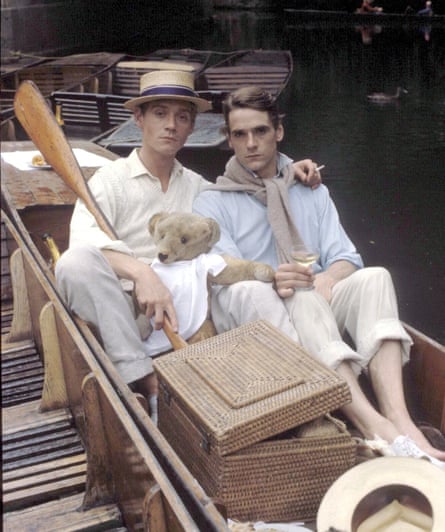

Scruton in this mode embodied two of the “quintessences” of Englishness identified by Barnes in England, England: “snobbery” and “whingeing”. Nevertheless, the vendors of Englishness had judged their market well in the age of Reagan and Thatcher, when the passion for social privilege became de rigeur. A televised version of Brideshead Revisited, a novel breathless in its adoration of the well born, and contempt for everyone else, became one of the biggest British cultural exports to the US since the Beatles. Bedazzled by Jeremy Irons and Castle Howard, Ralph Lauren repackaged country-house poshlost for Americans, and even sold it back to the already Barboured English.

The Raj, lavishly filmed in the 1980s, reappeared in the English imagination as an aesthetic spectacle, provoking awe rather than embarrassment. Many Americans succumbed to this imperial chic as well; and made it more lucrative. Emerging just in time to cash in on empire-mania, Banana Republic’s range of khaki colonial wear offered an opportunity to vicariously quell, in jodhpurs and pith helmets, the mutinous natives of Sind and Punjab. In this sense, those British chancers who later crossed the Atlantic to exhort Americans to re-establish empire, and offer their expertise in governing Basra and Helmand, were only following the money.

Arguments for carnage in Mesopotamia certainly sounded more persuasive when made with the Oxbridge cocksureness of a Christopher Hitchens, the Orwell du jour. Indeed, Englishness as a mode of glamorously aloof and omnisciently clever elitism became one of England’s chief exports. Orwell had railed against England’s “idle rich”, “living on money that was invested they hardly knew where”, and “whose photographs you can look at in the Tatler … always supposing that you want to”. Benefiting from a zeitgeist of feeling intensely relaxed about the filthy rich, Tatler’s circulation rose, and international editions bloomed, ushering the tuxedoed and begowned demi-monde of Jakarta and Manila into the pleasures of Cool Britannia.

Old English nurseries of the imperial ruling class such as Harrow and Wellington opened franchises in Thailand and China, offering to transmit solemn lessons of white supremacy to crazy rich Asians. Two London-based publications run by the Oxbridge elite, the Economist and Financial Times, became the most widely consulted how-to manuals of financial globalisation, sagely instructing wannabes how to think and feel like the filthy rich, and even how to spend it.

¶

In Ballard’s last novels, England is reduced to offering up its cultural icons for Disneyfication to the world while preparing itself for authoritarian populism. The reality now seems to have closely approximated Ballard’s dystopic fiction all along. For, while Hugh Grant’s dimpled grin advertised the charms of the English family, its precious silver was being sold off. In a process witnessed in no other major western country, many great emblems of national power, prestige and glamour – British Steel, Rolls-Royce, Aston Martin, Bentley, Jaguar, Debenhams, British Home Stores, HMV, Cadbury, Gieves & Hawkes, Hamleys – have either disappeared or gone into foreign hands since the 1980s. In September Thomas Cook, which once sold holidays to Churchill, became insolvent, stranding thousands of customers abroad and forcing the government to mount its biggest civilian rescue operation since Dunkirk.

It is only in such a “stagnant, involuted atmosphere of a world near the end of its tether” that Powellism would become hegemonic, Tom Nairn predicted in 1970, healing wounded English pride with reactionary balm, and appealing “to the (perfectly justified) national feeling of frustration and anger”. More importantly, “because this feeling is so inarticulate, and so divorced from the genteel cliches of the establishment”, Powellism could “suggest convincingly that something is profoundly wrong and that something must be done about it”.

As Boris Johnson never tires of repeating: Get Brexit Done. Nothing like a dose of hard Brexit, he suggests, to toughen the national mind and body for the bracing climb to the sunny uplands of Empire 2.0. Like Powell, he presents himself as the saviour of England’s matchless destiny against the ditherers. And, election rhetoric notwithstanding, he shares Powell’s and the Brexiters’ conviction that a higher dose of deregulation and privatisation will make England great again. More disingenuously than Powell, he ridicules the piccaninnies as well as the aliens in black letterboxes, and reaches out to the Home Counties colonels with promises to lock up swarthy criminals and throw away the key. There should be no mistaking the neo-fascistic cults of unity and potency he promotes, and the insidious forms they assume in England’s tabloidised media.

In Ballard’s last novel, Kingdom Come (2006), which drew inspiration from Robert O Paxton’s classic book The Anatomy of Fascism, English nationalism turns sadistically against those Powell stigmatised as hostile aliens. However, violent racism, which has exploded in recent years, is not nearly as sinister as the steady hardening of Powellite verities into bien pensant opinion. Centrist dads as much as unteachable Brexiters are likely to invoke his much victimised silent majority of ordinary, decent men, dispossessed by immigrants and then gagged by politically correct academics and journalists. Thus, as Simon Jenkins recently stated in the Guardian, Brexit “was about how far Britons can define and protect the character of where they live”.

With Brexiters in the ascendant, politically as well as culturally, the triumph of Powellism is complete. But we may be looking at an instance, to borrow a term from the Bush administration, of “catastrophic success”. For Powellism remains, in its moment of hegemony, a symptom of rather than a cure for the seemingly insoluble crisis that Orwell diagnosed: the dwindling material basis of an ex-imperialist country that is unable to break, in a globalised world, with its antique assumptions of power and self-sufficiency, and whose fundamentally cynical Bagehotian mode of politics, in which the will of the few was passed off as the will of the many, is broken, unable to innovate and deal with change, or defuse the anger of those victimised for so long by social and economic inequity.

“The life of nations,” Powell argued, “no less than that of men is lived largely in the imagination.” But nations that are too extravagantly imagined eventually pay a steep price for their system of self-delusions. Postcolonial India turns on itself in fury and frustration as its dream of power and glory explodes. England’s post-imperial self-reckoning feels harsher, largely because it has been postponed for so long, and the memories of power and glory are so ineradicable. In the meantime, the most important elections of our lifetime approach, and, as Orwell warned, “a generation of the unteachable is hanging upon us like a necklace of corpses”.