Aging

The Reciprocity of Need

Multiple life choices face aging mothers. Who makes those decisions?

Posted December 6, 2018

At the start of life, humans are unable to walk, speak, or control their bladder and bowels. That is who we creatures are at our beginnings, and if one has a healthy lifespan, who we once again become at its ending. A mother initially provides those functions the infant cannot navigate, then that infant may provide them for the mother as she becomes unable to perform what gerontologists have identified as the ‘activities of daily living.’

----

My mother looks up at me with a combination of shyness and pride. Her naked body is submerged in the bathwater as I perch on the toilet seat beside her.

“Look honey. It’s easy for me to get into the tub. I just get in when it’s empty and slowly let the water come in.”

“But Ma, it’s slippery and cold to sit on enamel like that.”

“No, it’s not. The tub is perfectly comfortable. And this way, I don’t worry about ever slipping,” she ends in a triumphant voice.

I watch her soap her washcloth and run it along her paper-thin skin, happy to show me how she is managing. How she can take care of things herself. How she doesn’t need help and certainly doesn’t need to be in a 'place.'

When she feels sufficiently bathed, she opens the drain and shifts her body onto her hands and knees. Once there, she presses down with one hand on the edge of the tub and the other on the side of the sink, pulls herself up to standing and triumphantly, exits the tub.

“See,” she announces. “I told you I can get in and out of the tub just fine. Now you’ve seen it with your own eyes.”

My mother was 86 and I was 60 then, the age of my eldest daughter now. I looked at her through 60-year-old eyes, the same ones through which my daughter sees me. My mother was a proud woman, as am I. She fought her way into the middle-class and apprenticed herself to women she thought were sophisticated and well-educated so that she could dress, decorate her home, and talk about books and music knowledgeably without a trace of the poor girl she had once been. But as reading became difficult for her aging eyes, as speech became an awkward excursion through a field of scattered and lost words that fled as she approached, as walking required appliances to maintain her balance—objects she would never use in public, as her hearing diminished and she was unwilling to get hearing aids because they would show, even under her well-coiffed hair—her life grew smaller and more isolated, quieter and sadder.

She said little of this, not wanting to burden or upset me. She didn’t want to reveal any diminishment of her carefully curated autonomy. Her fear of becoming a needy old woman led her to reveal only partial truths and contradictory stories, and our long-distance phone calls became increasingly unsatisfying for both of us—she trying to reassure me that all was well, and me sensing that so much remained unspoken, both of us ending the call feeling unsatisfied.

My mother’s loss of freedom was complete after she lost her driver’s license. She called to demand my allegiance about this miscarriage of justice.

“First of all, I don’t even know why he was so upset. It wasn’t even my fault.”

“Who was upset? Did you hit something, Ma?”

“You couldn’t even call it a hit. Like a little bump, that’s all.”

“Are you ok?”

“Of course I’m ok. I told you it was only a little bump. It was the cop who was so unpleasant.”

“The cop? Did you hit a cop, Ma?”

“Not the cop. His car.”

There is a long silence that I don’t attempt to fill. She and I both know what this will mean.

“I may even sue,” she finishes in a small defeated voice.

The expected letter arrives within the week officially notifying her that her driving days are over. I’m grateful that she won’t eventually cause an accident, hurting either herself or someone else. I also know that her life has just grown more circumscribed and isolated.

She was still able to microwave a sweet potato for her dinner, but eventually, even that became too confusing. Eventually, I had to intrude into my mother’s life in a more authoritative way than either of us wanted. I insisted when I would rather have discussed, decided when I felt uncertain about her desires, and was rebuffed when I tried to open a conversation that would have led us to more clarity. My mother could no longer safely live alone and I had no room for her in my one-bedroom apartment. She and I were now facing the repeated promise I had made her, the promise that I would never put her into a place. But now a place was the only choice where she would be safe and fed, where she would take her necessary medications at the right time, and where I wouldn’t have to be so worried all the time. She was unhappy about it. So was I. But all the conversations that we hadn’t had led us to this inevitable moment.

These are the conversations I am trying to have with my daughters now that I am 80 and understand that there will come a time, sooner rather than later, where my speech, or my walking, my driving or my cooking will begin to decline, and I will need help. Unlike my mother, my sense of myself is not so centrally defined by those competencies. I want everything to be said. I want them to know how I am, when I no longer feel safe driving at night, when I need help navigating shopping or reading or bathing. I don’t want them to end our phone calls feeling unsatisfied because I have been unable to tell them what they need and want to know. My daughters and I work to find the balance between my autonomy and desire to make my own decisions to the degree I can, and their need for my safety, comfort, and well-being. This on-going shift in our historic roles is an unsettling one for each of us. But as an old woman whose life was shaped by feminism, I approach my aging and eventual death having learned that what is true needs to be unearthed from beneath the protective stories that mask it. Then said aloud. Then acted upon. Those were my earliest and still most important lessons.

Now I am very careful when I drive. I sense the time is approaching when I will decide to stop driving, first at night, then in the rain, then increasingly try to schedule my errands during clear daylight hours. I am aware that eventually, even that will become too taxing and I will have to recognize that I am becoming increasingly unsafe behind the wheel of a car. I have had three grab bars installed in my bathroom and move in slow motion when I shower, being careful to move around in the watery space with my full attention. Now, when I take my daily walk, I remain alert to roots, stones over which I might trip, potholes into which I might stumble, my once easy unthinking stride a thing of the past. I keep my phone with me all the time now—just in case.

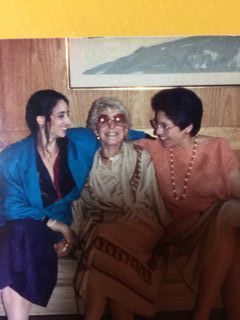

I am a mother of two middle-aged daughters and they watch me, just as I watched my mother. They still need me, still delight in the stories, the inside jokes, the shorthand. All of our history is alive when we’re together. They want to pickle me in formaldehyde and keep me alive forever. At least that’s what they jokingly tell me.

I am loved, valued, and I know, increasingly a responsibility. I am about to have knee replacement surgery and my youngest daughter will care for me. My body will be vulnerable and exposed. I will be her mother who needs her. She will be my daughter who is needed. Much as she needed me during the turbulent earlier years of her adulthood, I will need her as my aging vessel is propped up with titanium.

But she will not be “mothering” me. She will be engaging my need as my daughter. We will find our way forward and close the circle of our beginnings. The three of us. Together.