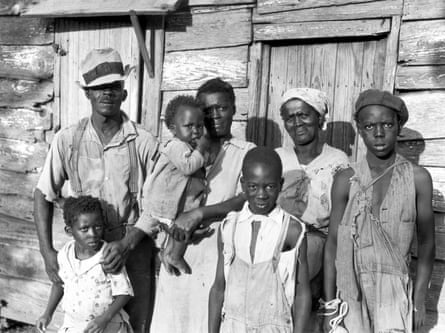

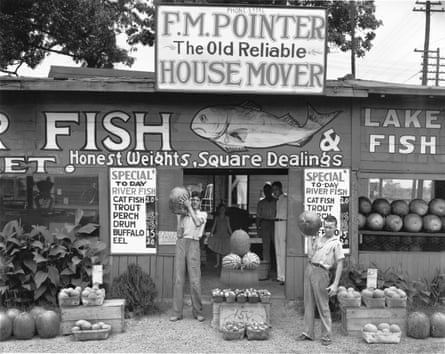

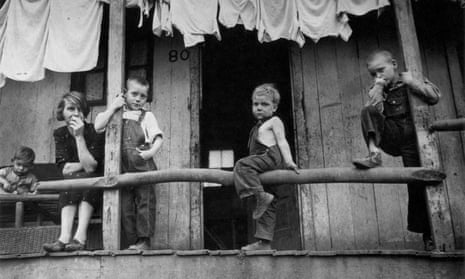

“It was the greatest group of photographers ever assembled in America,” says Hank O’Neal about the men and women hired by a US government agency – the prosaically named Farm Security Administration (FSA) – to create a portrait of a country coping with the effects of the Great Depression.

These days, the mainstream history of photography agrees with O’Neal, but it wasn’t always the case. Before O’Neal’s 1976 book A Vision Shared: A Classic Portrait of America and Its People 1935–1943, these photographers had largely been overlooked. “I got to work with nine of the 11 photographers, and the widow and widower of the two that were dead,” he says. “And you have to realise that in 1974 when I was talking with them, nobody was paying any attention to them. Nobody cared.”

If nobody cared before O’Neal’s book, plenty of people did after it. “The thing that was most astounding was that the book gathered around 120 reviews. It had three reviews in the New York Times alone,” he says. “It was a topic that was very hard to criticise. You could criticise me and say I wrote bad copy or something, but you couldn’t criticise the pictures – the Dorothea Langes, the Walker Evanses, the Ben Shahns, the Jack Delanos …”

Some of the book’s photographs define our image of the Great Depression, such as Arthur Rothstein’s Farmer and sons walking in the face of a dust storm, Cimarron County, Oklahoma, April 1936. But the pictures, which are presented chronologically, go far beyond the now-cliched view of the period: they show not just the south but all of America – from Pennsylvania to Nevada, Florida to Illinois to Vermont; and they were taken not only in cotton fields and shacks, but everywhere – in city streets, jails, churches, even racetracks. “What made the book special, and still does, is that these were the photographers’ choices. These weren’t my choices,” continues O’Neal, who interspersed lively and illuminating texts about each of the photographers among their chosen pictures. For the book’s 40th anniversary reissue, he has added a further chapter describing the positive impact the original book had on many of the photographers’ careers.

O’Neal’s interest was first triggered in the early 1970s after he came across a picture by Walker Evans and noticed a Library of Congress number on the back. He started digging around in the public archives, and eventually unearthed a photographic treasure trove of 80,000 prints. He resolved to track down the principal FSA photographers to get their take on the project, something that had never been done. “I had to travel around to find them. Jack Delano was in Puerto Rico. Russell Lee was in Texas,” he says. Even though Ben Shahn and Dorothea Lange had died, their spouses – who had accompanied them on many of their photographic trips – were able to help. “I drove down to Roosevelt, New Jersey, to see Bernarda Shahn. We talked and talked and her mind was so sharp, and so clear, that she could remember the names of people in the pictures from 1936. Just amazing. I did a trip to San Francisco, where I saw Paul Taylor, who had been married to Dorothea Lange. And I saw John Collier in San Francisco on that same trip, and I went down to Santa Barbara to see Marion Post, where she lived.”

Some of the photographers were closer at hand. “Fortunately John Vachon and Arthur Rothstein were in New York City,” he says. But one of the group in particular remained elusive: its most illustrious member. “I remember one day I had gone up to see John Vachon. We were talking about something and I told him about how I was having a great deal of trouble reaching Walker Evans. He wouldn’t answer letters and things.” Vachon helped find Evans’s phone number, and after repeated calls a reluctant Evans eventually allowed O’Neal to drive up to his house in Connecticut. “He said: ‘Let’s go down to the back porch and talk.’ And as we walked out the back I looked down by the back door and saw there was a whole pile of LP records. On top was Louis Armstrong or Fats Waller or some jazz person,” says O’Neal, who by then had already founded legendary jazz label Chiaroscuro Records. “I thought to myself: ‘I’m home free now’ because I knew 10 times more about jazz records than I did about photography. And that first meeting with Walker Evans was him interviewing me. He was astounded and envious that I actually knew Jimmy Rushing, who was a great American blues singer. He said: ‘I once was on a ship going to Europe with Jimmy Rushing, but I was too shy to talk to him.’”

Initially suspicious about O’Neal’s motives, Evans became an enthusiastic contributor to the project until one fateful night in April 1975. “The picture on the back of the book, of him taking a picture – he actually called me up and told me he had found it,” says O’Neal. “And then the next morning I got up and I had a phone call from Leslie Katz, who ran the Eakins Press [a specialist fine art publisher]. And Leslie said: ‘Isn’t it terrible about Walker Evans?’ And I said: ‘What are you talking about?’ He said: ‘He died last night.’ I said: ‘Cut it out. I talked to him last night twice’ … So an hour and a half after we had our conversation, he died. He had a stroke and died.”

But O’Neal looks back fondly on the project, and his time with the group was a lot of fun. “It was wonderful working with them. They were warm and generous,” he says. And there were some humorous – and awkward – moments along the way. “John Vachon lived up on the Upper West Side here in New York City. I already knew his daughter, Ann. I didn’t know that her father was a famous photographer or anything. Ann was a modern dancer,” he explains. “I found myself in a funny position with John. I not only knew his daughter, but I had taken a whole series of naked photographs of her. She was in a piece onstage in which she was covered in nothing but silver body paint.”

O’Neal believes the primary motivation shared by these photographers was social concern, and – at a time before television was an effective medium – they were trying to make a real difference to the plight of their fellow Americans. “Evans was the least passionate about the social aspects of the program of all of them. But most all of them were doing it because they thought it was really, really important. All of them had a social conscience,” says O’Neal, who thinks that a similar program could be just as effective now as it was back then. “There are places in the United States that need to be exposed and shown for the difficulties and privations that do exist. A photo project similar to this would be very helpful,” he says. “It’s important. These photographs changed people’s lives back then. And if you do them well enough and they are exposed properly, they could change lives today.”

- A Vision Shared: A Classic Portrait of America and Its People 1935–1943 is out now in the UK and US

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion