Two of the “freest economies” in the world are on fire. According to indexes of “economic freedom” published annually separately by two conservative thinktanks – the Heritage Foundation and the Fraser Institute – Hong Kong has been number one in the rankings for more than 20 years. Chile is ranked first in Latin America by both indexes, which also place it above Germany and Sweden in the global league table.

Violent protest in Hong Kong has entered its eighth month. The target is Beijing, but the lack of universal suffrage that is catalysing popular anger has long been part of Hong Kong’s economic model. In Chile, where student-led protests against a rise in subway fares turned into a nationwide anti-government movement, the death toll is at least 18.

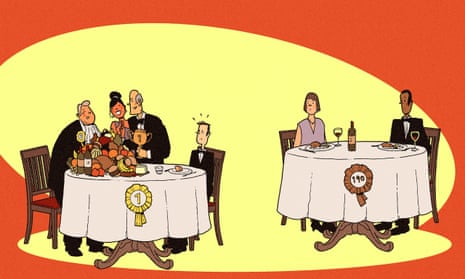

The rage may be better explained by other rankings: Chile places in the top 25 for economic freedom – and also for income inequality. If Hong Kong were a country, it would be in the world’s top 10 most unequal. Observers often use the word neoliberalism to describe the policies behind this inequality. The term can seem vague, but the ideas behind the economic freedom index help to bring it into focus.

All rankings hold visions of utopia within them. The ideal world described by these indexes is one where property rights and security of contract are the highest values, inflation is the chief enemy of liberty, capital flight is a human right and democratic elections may work actively against the maintenance of economic freedom.

These rankings are not merely academic. Heritage rankings are used to allocate US foreign aid through the Millennium Challenge Corporation. They set goals for policy-makers: in 2011, the Institute of Economic Affairs lamented that a rise in social spending was leading to a fall in Britain’s ranking. Tory MP Iain Duncan Smith even cited the Heritage index in support of a hard Brexit. Launching the 2018 index at the Heritage Foundation, Trump’s commerce secretary, Wilbur Ross, expressed hope that environmental deregulation and corporate tax cuts would reverse America’s decline in the ranking. Where did this way of framing the world come from?

The idea for the economic freedom index was born in 1984, after a discussion of Orwell’s 1984 at a meeting of the Mont Pelerin Society – an exclusive debating club of academics, policymakers, thinktankers and business leaders formed by Friedrich Hayek in 1947 to oppose the rise of communism in the east and social democracy in the west. The historian Paul Johnson argued that Orwell’s predictions had not come true; Michael Walker of the Vancouver-based Fraser Institute countered that perhaps they had. High taxes, obligatory social security numbers and public transparency about political contributions suggested we might be closer to Orwellian dystopia than we thought.

Walker saw this debate as the unfinished business of Milton Friedman’s 1962 book Capitalism and Freedom, which had suggested that political liberty relied on market freedom but had not proved it scientifically. Friedman was at the meeting, and, with his wife and co-author, Rose, agreed to help host a series of workshops on the challenge of measuring economic freedom.

The Friedmans gathered a crowd of luminaries, including Nobel prize winner Douglass North and The Bell Curve co-author Charles Murray, to figure out whether something as nebulous as freedom could be quantified and ranked. They ended up with a series of indicators, measuring the stability of currency; the right of citizens to own bank accounts in foreign countries and foreign currencies; the level of government spending and government-owned enterprise; and, crucially, the rate of individual and corporate taxation.

When Walker’s Fraser Institute published its first index in 1996 with a foreword from Friedman, there were some surprises. According to its historical overview, the second freest economy in the world in 1975 was Honduras, a military dictatorship. For the next year, another dictatorship, Guatemala, was in the top five. These were no anomalies. They expressed a basic truth about the indexes. The definition of freedom they used meant that democracy was a moot point, monetary stability was paramount and any expansion of social services would lead to a fall in the rankings. Taxation was theft, pure and simple, and austerity was the only path to the top.

“The ‘right’ to food, clothing, medical services, housing or a minimal income level,” the authors wrote, was nothing less than “‘forced labor’ requirements [imposed] on others.” The director of the index translated the vision into policy advice a few years later, writing in a public memo to the Canadian prime minister that poverty could be eliminated through a simple solution: “End welfare. Reinstitute poorhouses and homes for unwed mothers.”

Not content with mere economics, the Fraser Institute joined up with the Cato Institute in 2015 to publish the first global index of “human freedom”. They included all of the earlier economic indicators and supplemented them with measurements of civil liberty, rights to association and free expression, alongside dozens of others – but left out multiparty elections and universal suffrage. The authors noted specifically that they excluded political freedom and democracy from the index – and Hong Kong topped the list again.

What was going on? One answer is that the project of measuring economic freedom had made some of its authors question their prior assumptions about the natural relationship between capitalism and democracy. By the 1990s, Friedman, who had previously seen the two as mutually reinforcing, was singing a different tune. As he said in an interview in 1988: “I believe a relatively free economy is a necessary condition for freedom. But there is evidence that a democratic society, once established, destroys a free economy.” An enfranchised people tended to use their votes to pressure politicians into more social spending, clogging the arteries of free exchange.

In the workshops devoted to creating the indexes, Friedman cited the example of Hong Kong as evidence for the truth of this proposition, saying: “There is almost no doubt that if you had political freedom in Hong Kong you would have much less economic and civil freedom than you do as a result of an authoritarian government.”

Hong Kong’s former chief executive, CY Leung, agreed. During the “umbrella revolution” protests of 2014 he was asked why suffrage could not be expanded. His matter-of-fact response was that this would increase the power of the poor and lead to “the kind of politics” that favour the expansion of the welfare state instead of business-friendly policies. For him, the tradeoff between economic and political freedom was not buried in an index. It was as clear as day.

Economic freedom rankings exist inside nations, too. Stephen Moore and Arthur Laffer, two of Trump’s economic advisers, created comparable league tables for American states – which have proved drastically unhelpful in predicting economic success. The system has been rolled out by the Cato Institute in India, too, encouraging a deregulatory race to the bottom within national borders as well as across them. One of the authors of the report, Bibek Debroy, now chairs the Economic Advisory Council to Indian prime minister Narendra Modi.

Pinochet, Thatcher and Reagan may be dead. But economic freedom indexes carry the neoliberal banner by deeming the goals of social justice forever illegitimate and pushing states to regard themselves solely as guardians of economic power. Stephen Moore, who was a favourite earlier this year for Trump’s appointment to the Federal Reserve Board, put the matter simply. “Capitalism is a lot more important than democracy,” he said in an interview. “I’m not even a big believer in democracy.” Hong Kong’s financial secretary made much the same argument two weeks ago in London, when he cited the city’s top economic freedom ranking and reassured his audience that “alongside the protests, the business of business rolls on, unabated”.

By colour-coding nations, celebrating victors on glossy paper stock and giving high-ranking countries a reason to celebrate at banquets and balls, the indexes help perpetuate the idea that economics must be protected from the excesses of politics – to the point that an authoritarian government that protects free markets is preferable to a democratic one that redesigns them. At a time when the casting of ballots may lead to changes that threaten the freedom that capital has long enjoyed, the disposability of democracy in the vision of the index is what haunts us, from Santiago to the South China Sea to Washington DC.