Ready for a sadomasochistic Japanese satire inspired by Gulliver’s Travels author Jonathan Swift?

- Troupe BAN’YU-INRYOKU to perform play, set in universe of surrealism and dreamwork where deviant servants become masters, in Hong Kong in December

- Reworking of dramatist Shuji Terayama’s experimental production features rock and opera soundtrack, striking visual imagery and fantastic machines

Japanese art and culture has long been a source of inspiration for Western artists. Since the 1850s, when Japan’s era of isolation came to an end, the craze for all things Japanese has had a huge impact on Western visual arts.

For example, Edo period (1603-1867) woodblock prints, called ukiyo-es, inspired painters including Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Vincent van Gogh, and Gustav Klimt – whose work led to the development of art nouveau.

We would like to make some kind of internal revolution, change or transformation, take place by using Nuhikun, Shuji Terayama’s theatrical performance as a detonator

Yet the cultural exchange also flowed in the opposite direction and has led to many of the West’s great works of art, stage and literature being reinterpreted through a Japanese lens.

Here are five thought-provoking Japanese takes on Western works, including Nuhikun, a play based on an unfinished satirical essay, Directions to Servants (1731), by Irish-born writer Jonathan Swift – best known for Gulliver’s Travels – which will be performed in Hong Kong in December.

Nagano’s Wuthering Heights

Wuthering Heights (1847), the Gothic novel by English novelist and poet Emily Brontë, has spawned more than 20 Japanese interpretations since it was first translated by Yasuo Yamamoto in 1932.

Versions include stage productions, a children’s book, and various manga series, such as a yuri lesbian-themed manga by Takako Shimura.

One recent version is by award-winning author Minae Mizumura, whose contemporary rewriting of the story, Honkaku Shosetsu, was published in 2002 and translated into English by Juliet Winters Carpenter in 2013.

If daily life has become a rut and you want a shock, such as when you meet an old lover by accident in a town, then come to the theatre [to see Nuhikun]

The complex narrative in Mizumura’s work, which moves from the streets of New York to the mountains of Karuizawa, in Nagano prefecture, positions contemporary Japanese women in a similar state to Emily Brontë and her famous sisters.

Victorian women were a product of the modernity created by the Industrial Revolution, which offered unprecedented opportunities for women. Japanese women of the last few generations have been given far more freedom, too.

Mizumura’s novel suggests that embracing these freedoms creates conflict between reassuring traditional values and the thrill of following your heart – a theme that is at the centre of Wuthering Heights.

Manga Mephisto

Fausuto (1950) is a graphic novel by Osamu Tezuka (1928–1989), who is considered the father of manga.

Based on German writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s play Faust, Tezuka’s main character, Mephisto, is an arrogant, troublesome devil, who takes a bet with God in heaven that he can lead astray the Lord’s favourite scholar, Dr Faust.

The manga largely follows the plot of Goethe’s original, a text Tezuka greatly respected and referred to throughout his career.

Tezuka illustrated his manga in cartoonish style – not to undermine the importance of Goethe’s masterpiece, but to raise the status of manga in popular culture, which was not appreciated as an art form at the time.

His later manga adaptations of classic literature featured Pinocchio (1952), Cyrano the Hero and Crime and Punishment (both 1953).

Shakespearean samurai

Theatre director Yukio Ninagawa (1935-2016) is known for his bold, sometimes controversial, interpretations of Shakespeare’s plays.

His acclaimed sakura (or cherry blossom) version of Macbeth, which he created in 1980, has been performed around the world.

Like Akira Kurosawa’s 1957 Throne of Blood, one of the great Shakespeare films of all time, Ninagawa’s version of Macbeth replaces 11th-century Scotland with feudal Japan. Macbeth is a samurai, richly clad in silk and armour, and the witches are white-faced kabuki actors.

The staging is a multicultural amalgamation with Macbeth’s struggles of conscience set evocatively to Buddhist chanting and Western music by Gabriel Fauré and Samuel Barber.

The ever-present sakura, which falls in soft drifts across the stage or is stitched on to Lady Macbeth’s kimono, is a visual symbol of the play’s fascination with death: just as cherry blossoms are fleeting, so is life – a Buddhist idea, and a key theme in Shakespeare’s masterpiece.

The play was performed to rave reviews in Hong Kong by the Ninagawa Company in 2017.

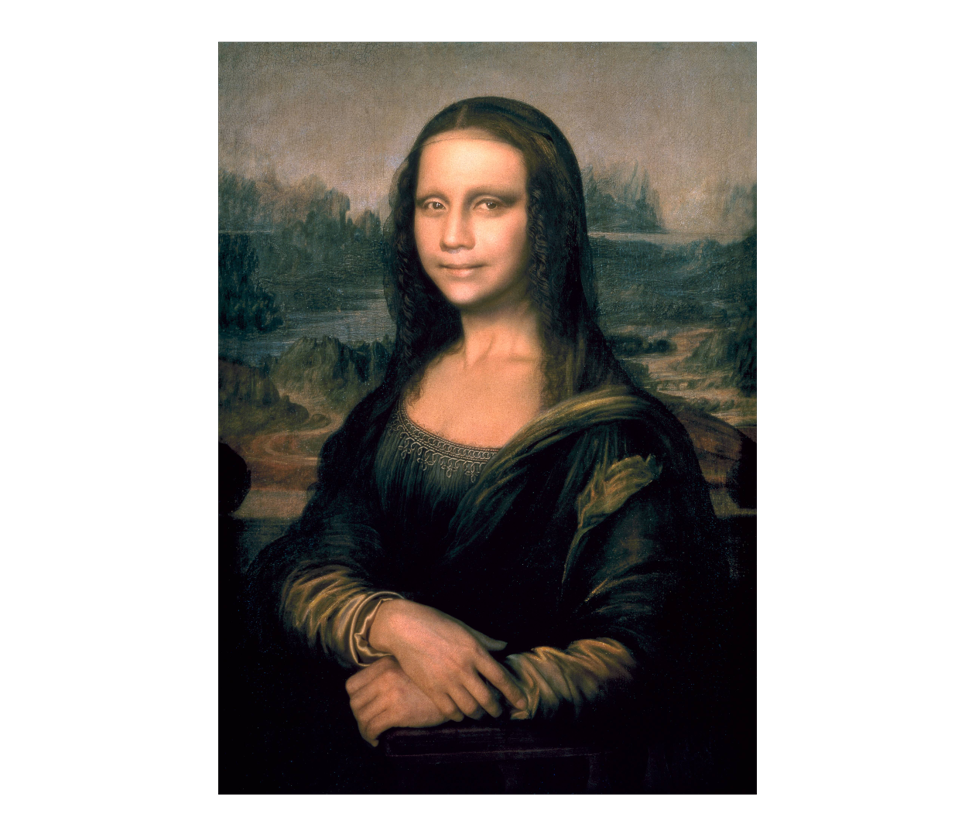

Morimura as Mona Lisa

Japanese appropriation artist Yasumasa Morimura recreates iconic works of Western art by putting his face into the portraits. He has become the Mona Lisa, artist Frida Kahlo, and Edouard Manet’s Olympia.

He has also added his face into photographs or film stills, becoming actresses Marilyn Monroe and Jodie Foster, and even, controversially, Japan’s former leader, Emperor Hirohito.

He uses extensive props and digital manipulation to create his images, which results in unsettling, uncannily similar versions to the originals.

Simultaneously reverent and satirical, his self-portraits investigate traditional notions of beauty while showing appreciation for the art he has appropriated.

In the works, he is an androgynous outsider who is peering back at his audience through an assumed Western gaze, but with the absent identity of a Noh performer.

Satire on rebellious servants

The play Nuhikun is set in a mansion of deviant servants without the presence of a master. When servants become masters, the unexpected occurs, exposing the audience to a sadomasochistic universe of surrealism, dreamwork and Brecht-like theatrics of defamiliarisation.

Swift’s essay was reworked for the stage by avant-garde poet, dramatist, writer, film director and photographer Shuji Terayama (1935–1983), considered one of Japan’s most productive and provocative creative artists.

Since Terayama first performed the play with his experimental theatre troupe, Tenjo Sajiki, in Tokyo in 1978 it has been performed more than 100 times and featured in tours in more than 30 cities worldwide.

After Terayama’s death, Tenjo Sajiki dissolved, but one of its key artists Takaaki Terahara, known professionally as Julius Arnest “J.A.” Caesar, or J.A. Seazer, formed the troupe, A Laboratory of Theatre Play BAN’YU-INRYOKU, with most of the original company members.

BAN’YU-INRYOKU will perform Terayama’s work, with its layered language, rock and opera soundtrack and striking visual imagery, including fantastical onstage machines, on December 13 and 14 at the Hong Kong Cultural Centre.

Seazer says Nuhikun explores the rebellion of the slave under the edict, “Rules that concern all servants in general”, found in the original work.

“You don’t have to go if your husband calls, ‘Someone!’,” he says. “Only dogs are called ‘Someone!’.

“The play draws on the language of [children’s book author] Kenji Miyazawa, as Terayama was interested in his fairy tale world, especially in how he expresses intense humanity.

“The mansion in which Swift sets his essay is another key aspect we explore. And then Terayama’s favourite eroticism, which is found in the world of [French novelist and playwright] Jean Genet, is key to Nuhikun as well.”

Seazer says he adapts each performance of Nuhikun to the specifics of each stage on which the play is performed on – often swapping or adding scenes, replacing actors and changing the lighting and music.

“As Terayama said, ‘Theatrical performance is to wake up and make something happen’,” he says.

“We would like to make some kind of internal revolution, change or transformation, take place by using Terayama’s theatrical performance as a detonator.

“We can’t say what the internal transformation will be specifically because each individual is affected differently.

“I would like audiences to visit the theatre and experience Nuhikun for themselves. We would like them to enjoy ‘coincident encounters’, as Terayama termed it.

“If daily life has become a rut and you want a shock, such as when you meet an old lover by accident in a town, then come to the theatre. Surely you will meet something in yourselves!”