Well before the world associated the phrase “me too” with sexual assault, Jian Ghomeshi was a popular Canadian radio host and musician. In 2014 and 2015, however, he became the subject of numerous allegations of sexual assault, which included biting, choking, and punching women in the head. In 2016, he was acquitted on a number of criminal counts when the judge said that the three women who testified in court against him had changed aspects of their story or had failed to reveal information to law enforcement. But these were only a few of the accusations against Ghomeshi, which eventually were made by more than 20 women. He also avoided criminal charges in a separate trial by signing a “peace bond” and apologizing to his victim.

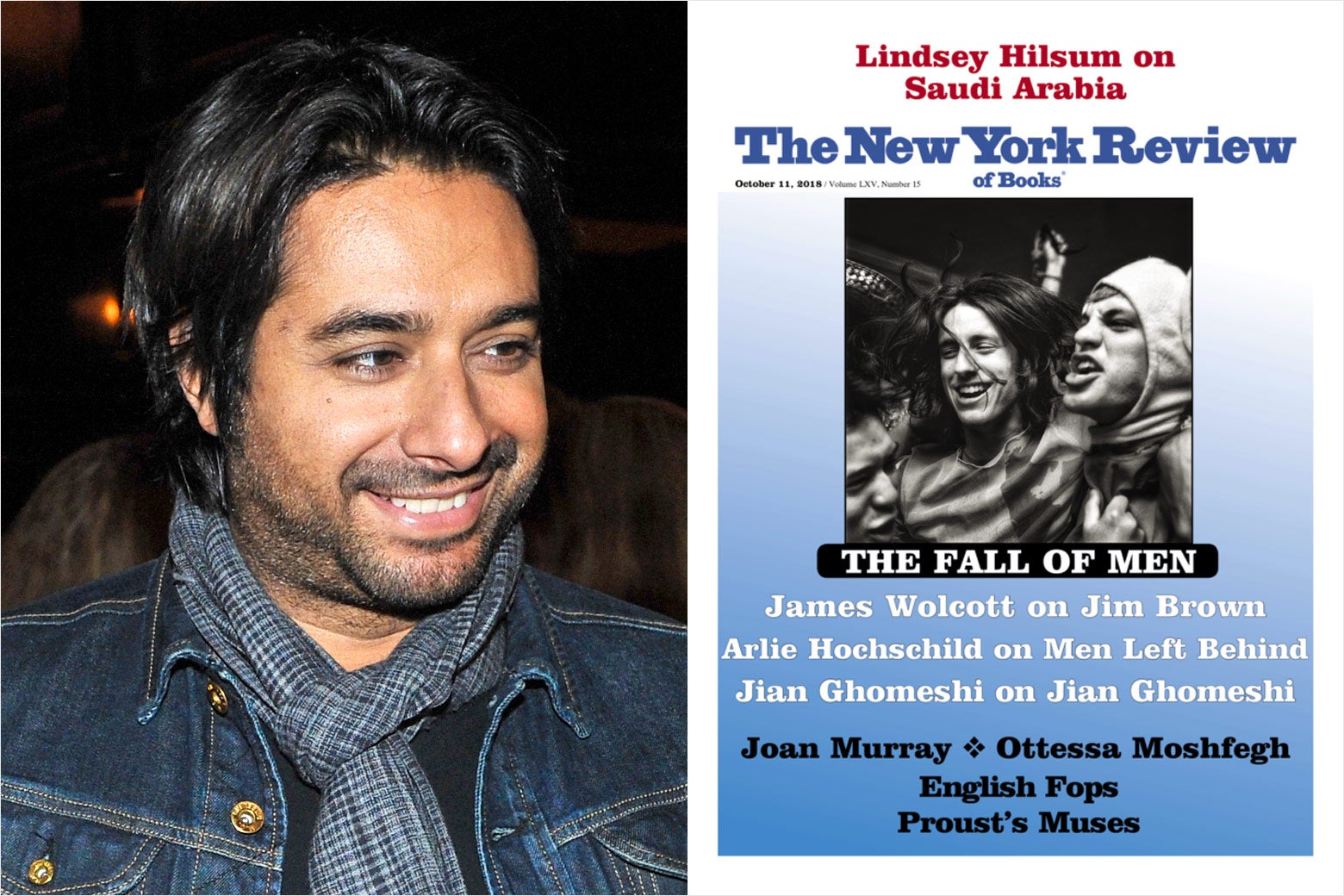

Now, Ghomeshi has published a long essay in the New York Review of Books, titled “Reflections From a Hashtag.” In it, Ghomeshi aims to “inject nuance” into his story and says he has faced “enough humiliation for a lifetime” as a victim of “mass shaming.” He also claims to have learned some lessons that have made him a better man: “I have spent these years trying to listen, read, and reflect,” he writes, adding that he now understands that he could be too demanding on dates. Still, he denies the vast majority of the accusations. The piece is promoted on the cover as part of a package on “The Fall of Men” and lands on the same week that Harper’s published a long first-person essay by John Hockenberry, who last year was accused of harassing several female colleagues at WNYC.

I recently spoke by phone with Ian Buruma, the editor of the New York Review of Books, about the decision to publish the Ghomeshi piece, which has already proven controversial. (Full disclosure: I have met Buruma several times, and he offered me a job last year after he took over the NYRB.) During the course of our conversation, which has been edited and condensed for clarity, we discussed the genesis of the piece, the ethics of publishing people who do bad deeds, and why the specific nature of Ghomeshi’s behavior is not really Buruma’s “concern.”

Isaac Chotiner: How did this piece come about?

Ian Buruma: I met, through another editor, many months ago, Jian Ghomeshi, whom I hadn’t met before and who told me his story and said that he was interested in writing about it. I was interested in the subject, which as we discussed then, the first time I saw him, was what it was like to be, as it were, at the top of the world, doing more or less what you like, being a jerk in many ways, and then finding your life ruined and being a public villain and pilloried. This seemed like a story that was worth hearing—not necessarily as a defense of what he may have done. But it is an angle on an issue that is clearly very important and that I felt had not been exposed very much.

Was it at a social occasion that you met?

No, no, it was a coffee to discuss the prospect of writing.

The editor had … I don’t know how he knew Ghomeshi. I have no idea. But the three of us had coffee and his story was discussed and he expressed an interest in writing about it. And I said I find it an interesting story, so I will read whatever you come up with. [Note: When I called Buruma back to ask whether the other editor worked at a different publication—as I had perhaps wrongly assumed from his first answer—he did not answer, telling me, “It’s irrelevant. It’s neither here nor there.”]

Were there in-house objections to the piece?

No. We had a proper office discussion and everybody expressed their views and not everybody agreed. But all views were aired and in the end, when the decision was made, the office stuck together.

Was there a gender breakdown during the discussion?

I would say not necessarily just in this particular case. I would say that on issues to do with #MeToo and relations between men and women and so on, there isn’t so much a gender breakdown as there is a generational one. I think that is generally true. I don’t think our office is in any way unusual. I think people over 40 and under 40 often have disagreements about this.

How old are you?

I’m 66.

Are you then on the predictable side of that divide, given what you said?

I wouldn’t want to categorize myself quite so starkly. Like everybody who thinks about these issues, I have ambivalent feelings about it. I have absolutely no doubt that the #MeToo movement is a necessary corrective on male behavior that stands in the way of being able to work on equal terms with women. In that sense, I think it’s an entirely good thing. But like all well-intentioned and good things, there can be undesirable consequences. I think, in a general climate of denunciation, sometimes things happen and people express views that can be disturbing. I wouldn’t say that I have an unequivocal view of it.

Do you think what happened to Ghomeshi is an “undesirable consequence?”

I think it has undesirable, or at least unresolved, aspects to it. I think nobody has quite figured out what should happen in cases like his, where you have been legally acquitted but you are still judged as undesirable in public opinion, and how far that should go, how long that should last, and whether people should make a comeback or can make a comeback at all—there are no hard and fast rules. That’s an issue we should be thinking about.

But—

Hang on. Hang on. The reason I was interested in publishing it is precisely to help people think this sort of thing through. I am not talking about people who broke the law. I am not talking about rapists. I am talking about people who behaved badly sexually, abusing their power in one way or another, and then the question is how should that be sanctioned. Something like rape is a crime, and we know what happens in the case of crimes. There are trials and if you are held to be guilty or convicted and so on, there are rules about that. What is much murkier is when people are not found to have broken the law but have misbehaved in other ways nonetheless. How do you deal with such cases? Should that last forever?

There are numerous allegations of sexual assault against Ghomeshi, including punching women in the head. That seems pretty far on the spectrum of bad behavior.

I’m no judge of the rights and wrongs of every allegation. How can I be? All I know is that in a court of law he was acquitted, and there is no proof he committed a crime. The exact nature of his behavior—how much consent was involved—I have no idea, nor is it really my concern. My concern is what happens to somebody who has not been found guilty in any criminal sense but who perhaps deserves social opprobrium, but how long should that last, what form it should take, etc.

O. J. Simpson was not found guilty in a criminal trial. I assume, even if he didn’t have other issues, we might have paused before asking him to write an essay.

That is true, but he was found guilty in a civil trial.

I think even if he hadn’t been is perhaps the point to be made. But let’s also note that Ghomeshi signed a peace bond and avoided another trial by apologizing to a victim. And these allegations were from more than 20 women. We don’t know what happened, I agree. But that is an astonishing number, no?

I am not going to defend his behavior, and I don’t know if what all these women are saying is true. Perhaps it is. Perhaps it isn’t. My interest in running this piece, as I said, is the point of view of somebody who has been pilloried in public opinion and what somebody like that feels about it. It was not run as a piece to exonerate him or to somehow mitigate the nature of his behavior.

You say it’s not your “concern,” but it is your concern. If you knew the allegations were true, I assume you would not have run the piece.

Well, it depends what the allegations are. What you were saying just now was rather vague.

Punching women against their will.

Those are the allegations, but as we both know, sexual behavior is a many-faceted business. Take something like biting. Biting can be an aggressive or even criminal act. It can also be construed differently in different circumstances. I am not a judge of exactly what he did. All I know is that he was acquitted and he is now subject to public opprobrium and is a sort of persona non grata in consequence. The interest in the article for me is what it feels like in that position and what we should think about.

In his piece, he writes, “In October 2014, I was fired from my job at the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation after allegations circulated online that I’d been abusive with an ex-girlfriend during sex.” But it was not about online rumors. The Toronto Star, a famed and respected newspaper, was about to publish a big piece, and that is why he resigned, correct?

It’s a respected newspaper, yes.

But you don’t think that’s misleading in any way?

Not really, but again, I am not judging him for the exact rights and wrongs of what he did in the past.

I am asking you about what he wrote in your magazine.

No, I don’t think so.

He also writes, “In the aftermath of my firing, and amid a media storm, several more people accused me of sexual misconduct.” Is “several” sufficient for more than 20 women?

Well, in a literal sense, it is. It might have been better to mention the exact number, possibly so.

One passage states, “One of the charges was separated and later withdrawn with a peace bond—a pledge to be on good behavior for a year. There was no criminal trial.” He doesn’t mention that he was also forced to apologize, which feels crucial in trying to ascertain his innocence or guilt.

I don’t have the piece right in front of me. What exactly did he write?

“One of the charges was separated and later withdrawn with a peace bond—a pledge to be on good behavior for a year. There was no criminal trial.” There was no mention of the apology.

I think the fact that he doesn’t mention an apology does not really add or take away anything from the story at hand, which is what happened afterward and what happened to him. It is a personal account, which by the way, and I think should be said, is part of a package in the magazine. It doesn’t stand on its own. It’s with two other articles that give different accounts and different angles on male behavior.

Do you not feel that there is a statement being made putting him on the cover, which says “The Fall of Men,” next to these other pieces? The headline of the piece is “Reflections From a Hashtag,” which feels dismissive of #MeToo to me.

No, not at all. In none of these pieces is anybody making an argument against #MeToo. All we have done is take three pieces, which I would hope help the readers to think through a very fraught issue in our time. It is certainly not a statement against #MeToo. It is trying to understand bad male behavior.

When a guy who has avoided real punishment says he has had “enough humiliation for a lifetime” and is a victim of “mass shaming,” that does seem to be a comment on what follows accusations.

That is his comment. It is a personal account. So he is expressing what it felt like to him. It is not me saying that. It is not me saying that’s good. It’s not me saying that’s bad. You need to find as many fresh ways to analyze, express, and describe what’s going on as you can, and this is one angle I hadn’t read yet. Until I read [John] Hockenberry in Harper’s.

The New York Review of Books published Mary McCarthy and Elizabeth Hardwick. It’s prestige. I assume you only print pieces that reach a certain quality as written work.

Yes, that’s true. The point being that everyone whose name is above an article at the Review has to be absolutely beyond reproach in their private and public life? I don’t think so.

No, you have published Naipaul and Mailer, who did not behave well with women. This seems different. Last question: Last year, near the end of which you took over, VIDA, an organization that measures gender parity in publishing, reported that your publication “had the most pronounced gender disparity of 2017’s VIDA Count, with only 23.3% of published writers who are women.” Are you making an active effort to change that?

Yes. We are very conscious of having as many women writing in each issue as we can. I don’t believe in quotas. I believe in having things that are of the greatest interest. But we make an effort with every issue to have as many female voices as we can get.

Have you heard any complaints from contributors about this piece?

No.

Last question: If—

Many last questions.

If Harvey Weinstein wanted to write an essay for you on his post-#MeToo experiences, assuming he isn’t convicted, or the statute of limitations had passed, would you consider publishing it?

I don’t think I can answer that question because it is not only a hypothetical but an extremely unlikely event, since he has been accused of rape, which Ghomeshi was never accused of. I think it’s a very different case. If somebody was accused of rape—let alone convicted for it—no, I wouldn’t have the same attitude. I think that is partly the problem. People very quickly conflate cases of criminal behavior with cases that are sometimes murkier and can involve making people feel uncomfortable, verbally or physically, and that really has very little to do with rape or criminal violence. I think it is a mistake to too quickly dissolve those distinctions.

Read more from Slate:

• Among All the Other Problems With Ghomeshi’s NYRB Piece, It’s a Terrible Personal Essay

• I Received Some of Kozinski’s Infamous Gag List Emails. I’m Baffled by Kavanaugh’s Responses to Questions About Them.

• Why We Almost Believed Les Moonves Would Get Away With It