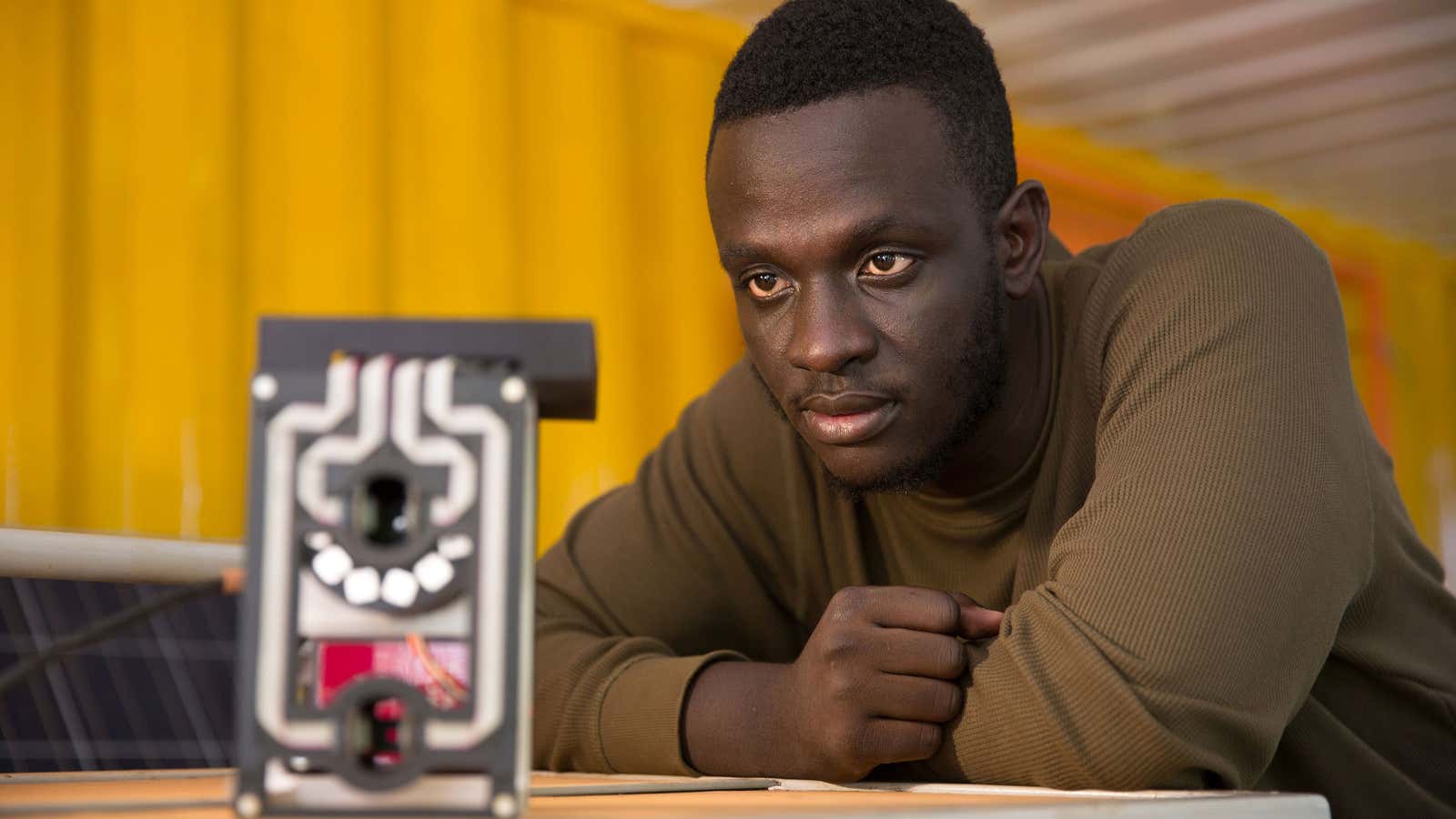

The $33,000 Africa Prize for Engineering Innovation has been awarded to a 24-year old Ugandan engineer for his invention of a bloodless malaria test. Before now, small blood samples taken from suspected patients in hospitals or pharmacies were used to test for malaria but with Matibabu, the device developed by Brian Gitta and his team, there is no need for pricking.

When a person is infected, the malaria parasite takes over a vacuole of the red blood cells and significantly remodels it. For Matibabu to work, it is clipped onto a person’s finger and using light and magnetism, a red beam of light scans the finger for changes in colour, shape and concentration of the red blood cells. A result is produced within a minute and sent to a mobile phone linked to the device.

Matibabu (Swahili for ‘treatment’) is low cost, reusable and because the procedure is non-invasive, does not require specialist training.

Malaria alone costs Africa 1.3% of its GDP and most of the children under five years of age who die everyday because of malaria are in sub-Saharan Africa. The disease infects some 300 million to 600 million every year around the world, according to Unicef. But Sub-Saharan Africa alone accounts for 90% of the world’s 580,000 annual malaria deaths.

However, malaria deaths in Africa have significantly been reduced by 66% since the turn of the century—thanks to a raft of interventions such as freely distributed treated bed nets and increased funding for the purchase of improved medicines. Two African countries (Morocco and Egypt) have already been declared malaria free and six more (South Africa, eSwatini, Botswana, Comoros, Algeria and Cape Verde) are on course to eliminate the disease by 2020.

Just like Matibabu, the African scientists and engineers have been at the forefront of innovations and discoveries to consign malaria to history. In 2015, scientists in Nigeria successfully developed a product to test a patient’s urine for malaria, rather than blood test. Scientists at the University of Cape Town found a compound that has the potential to block human transmission of the malaria parasite and in Burkina Faso, a low cost mosquito-repelling soap made from natural herbs has also been developed.

In Zanzibar, a team of locals and foreigners are using drones to map mosquito breeding areas and to use that information to help in the efficient use of larvicide to neutralise them. Pilots of a malaria vaccine will also take place this year in three countries.

But the fight to end malaria in the world by 2030 as set in goal three of the UN’s SDGs is hard in part because of increased drug resistance by the parasite ably aided by the ubiquity of fake and substandard malaria drugs across Africa.