Here is a question you can bring up under Any Other Business at your next meeting: would all this be going better if the robots were in charge?

To listen to the claims of some “artificial intelligence” evangelists, the answer to that question might be yes. In California IBM’s Project Debater machine has just achieved an honourable draw in debates with two actual human beings.

While the humans scored well with facial and hand gestures – something that for now is still beyond Project Debater’s capabilities – the robot impressed with its grasp of data and use of evidence. Hearts may not have been moved but minds were swayed. Admittedly, many in the room were IBM staff, so the geek factor may have been unusually large on this occasion. Question Time this was not.

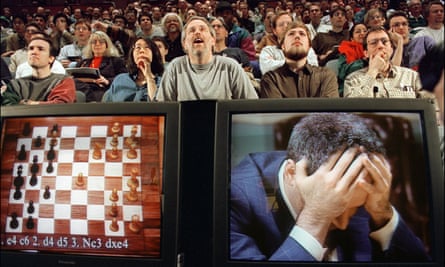

Are there any limits to what the AI machines can do? Er, yes, there are limits. But it is impossible to deny that progress is being made, and rapidly too. First it was said that the subtleties of chess would make it impossible for the then (human) world champion to be beaten. Wrong. Then it was argued that the Chinese game of Go, far more complex still, would resist the rise of the robots. Wrong again. And now artificial intelligence is creating debaters to take on modern-day Ciceros and give them a run for their money.

Why not unleash some of this AI brilliance into the boardroom, it is suggested. Get some cool analytical heads – or “heads” – on the case. Robots will not be influenced by emotional appeals. They will focus on facts and be objective about data. They will balance risk and reward decisions on the basis of probabilities. Sure, this might be less entertaining than an episode of The Apprentice, if that is the sort of thing you like. But maybe businesses and organisations would be better served by computational rigour at the top rather than subjective, bullying outbursts.

It might have been preferable for Carillion’s employees, contractors and shareholders if an unflinching accountancy algorithm had been able to speak up and declare the board’s assessment of the company’s finances to be ridiculous. Computers do not have relationships to manage or careers to plot. They should be able to tell the unvarnished truth at all times.

But there are one or two reasons why Project Debater may not quite be ready to take its place in the boardroom. First, it has a female voice – and we all know how welcome female voices are at the top of many FTSE companies. Perhaps it’s a good thing that these machines don’t have feelings. It might otherwise be a bit crushing for the computer to hear the traditional response: “Well, that’s a very interesting point, Project Debater. Perhaps one of the men would now like to make it so we can discuss it properly?”

More seriously, we know that supposedly objective, dispassionate algorithms can in fact be shot through with the prejudices of the people who have written them. Garbage in still leads to garbage out. So you would have to be very careful how you deployed AI machinery anywhere near the decision-making process. You would still need a few grown-up humans nearby to supervise.

What’s more, we shouldn’t get too carried away with what the IBM robot just did. Olivia Solon’s candid assessment for the Guardian was that “it lacked linguistic precision and argumentative clarity”. Similar criticisms have not prevented others from getting to the top of course. But could we accept this sort of thing from a machine for very long? Fragmented Trumpian sentences and chilly Maybot utterances do not exactly enthuse everybody, but at least these two figures are more or less recognisably human.

Data isn’t everything when it comes to decision-making. Experience, intuition, hunches, imagination and judgment all matter too. Would AI have given us the Sony Walkman or the Apple Macintosh? I doubt it. Robots are pretty unimaginative. They could enhance or support human choices, however.

As the writer Margaret Heffernan has observed: “Artificial intelligence is unlikely to be the answer to genuine stupidity.” Man, woman and machine need to work together to solve our problems. But for the foreseeable future it will be a human being whose finger is on the machine’s off switch, and rightly so.