Everest for the time-pressed executive

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

On the fourth week of their historic assault on Everest in 1953, Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay were still establishing base camp after the long trek from Kathmandu. It would be a further six weeks before the men conquered the mountain. On the fourth week of his attempt to climb Everest, 65 years later, Eduard Wagner was lying on a beach in Koh Samui, Thailand. The German businessman had completed his expedition early, after reaching the top on May 21. “I could have been back at my desk in three weeks,” he says.

The 40-year-old from Munich had joined the “Flash” — signifying high-speed — expedition offered for the first time this year by Furtenbach Adventures. The Austrian operator kits out its clients with altitude simulation tents which they rig up over their beds at home and sleep in for six weeks before departure. The theory is that the tents, in which oxygen levels are reduced, stimulate production of red blood cells and thus reduce the number of rest days and acclimatisation climbs, or “rotations”, needed on the mountain. While the 1953 expedition took almost five months in total, and most Everest expeditions today take around 65 days, Furtenbach’s Flash expedition was planned as a 28-day round-trip (and in the event, perfect weather meant all its members were finished within 23). If that’s too long, the operator also offers Flash trips to other celebrated peaks — Manaslu (at 8,163 metres, the world’s eighth-highest) in 21 days, Ama Dablam, Everest’s much-photographed neighbour, in 17 days, and Aconcagua, the highest mountain outside Asia, in just two weeks.

The only catch is the price — the Flash Everest expedition costs $110,000 — but Furtenbach is catering to a burgeoning high-end market on Everest. While its focus is on bringing the summit within vacation range for time-pressed executives, other companies are adding comforts more commonly found at luxury safari camps.

In other firsts this year, the Russian outfit 7 Summits Club put up its premium clients in heated canvas suites containing fully made-up beds with a desk next door. Charging $80,000 for the package, the company also flew in massage therapists, a top cruise-ship chef from Chile, and offered two Sherpa guides per climber. Its nine premium clients included Dmitry Tertychny, a 17-year-old pupil at England’s exclusive Charterhouse School, who climbed alongside his father Alex, a former Russian railway tycoon. Nepali group Seven Summit Treks, meanwhile, offered a $130,000 “VVIP” package, taking clients by helicopter from Kathmandu to Dingboche and thus cutting the base camp trek to just three days. Midway through the trip, expedition members were flown back to Kathmandu for several days’ rest in a five-star hotel before returning, refreshed, to the mountain.

Everest has long since ceased to be the stage for heroes in the mould of Hillary or Norgay. Today the 8,848-metre mountain stands as the zenith not of exploration but of the commercial adventure travel industry. Improved weather forecasting, better equipment, route-setting and abundant bottled oxygen have made it safer — as has the disappearance of the notorious Hillary Step, most likely as a result of the 2015 earthquake, now a gently-angled slope rather than a cliff. Big spenders who might previously have been put off a tougher or longer expedition are adding the mountain to their bucket lists.

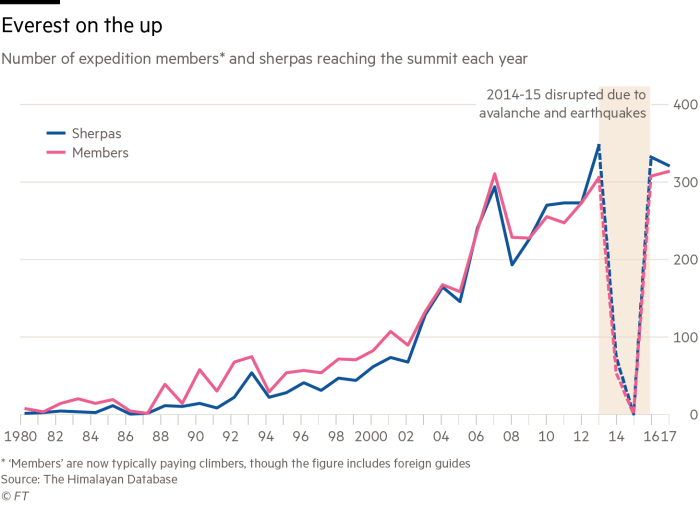

During this year’s spring climbing season, which drew to a close at the end of May, more than 700 people reached the summit, a new record. One expedition left cryptocurrency tokens on the summit as a publicity stunt; another carried up a statue of a former Nepalese king. More Sherpas now reach the top than paying climbers, as companies increasingly offer Sherpa support all the way to the summit, with the promise that clients need never climb alone.

Some companies are more subtle than others in their marketing. Seven Summit Treks says on its website that the “VVIP” service is for those who “want to experience what it feels like to be on the highest point on the planet and have strong economic background to compensate for your old age, weak physical condition or your fear of risks”. Perhaps the Nepali group’s copywriting has lost something in translation, but the idea of Everest as an achievable goal for unfit, rich amateurs of a certain age has raised new questions about respect for the world’s highest mountain.

“They’re redefining the concept of luxury on Everest, but all of these things are meaningless in the mountaineering sense,” says Ed Douglas, a British climber and editor of the Alpine Journal. “It’s still a personal achievement, but if you hose any problem with money, you generally come up with a solution.”

Kenton Cool, a British guide who reached the summit with clients for the 13th time this year, is dismayed by some of the inexperience he sees in the “death zone” above 8,000 metres. “You see people who’ve never even worn crampons before and I think, God, if I walked into your boardroom with zero experience, everyone would laugh at me. What part of you thinks this is a good idea?” Cool includes himself at the premium end of the market. He won’t reveal his prices, but they include two years of training and preparatory climbs. He says more than 90 per cent of people climbing Everest today are paying clients rather than members of the sponsored expeditions that were once the norm. In a poor region of Nepal, whose government charges foreign climbers $11,000 for an Everest permit, client vetting often starts and stops with their finances.

Eduard Wagner is by no means inexperienced. The automotive consultant has climbed more challenging routes closer to home, including the north face of the Eiger in Switzerland. Everest was do-able, but previously never a realistic ambition. “You have to spend a lot of time at base camp and that’s kind of empty time,” he says. “You can’t work, you’re just sitting around doing these rotations. I don’t like empty time.” When he heard about the 28-day package, his ears pricked up.

Lukas Furtenbach, an Austrian entrepreneur and mountaineer based in Innsbruck, traces the rise of high-end Everest to New Zealander Russell Brice, whose Himex company raised the bar in the 1990s, when Everest became commercial. Competition then brought prices down, while Nepali companies created the budget market. Furtenbach saw no way in, and resisted adding Everest to his list of destinations. But in 2016, when he got the chance to shoot a high-definition film on the mountain, he offered a few premium places at a lossmaking €35,000. “Of course everyone else hated us,” he recalls.

Furtenbach charged €50,000 last year, which he says only covered costs, and moved to the relatively quiet northern base camp on the Tibetan side, an alternative to the more famous southern camp in Nepal (both are above 5,000 metres, but the Tibetan camp is accessible by road, making it easier to install better facilities). He was already issuing the hypoxic altitude tents to clients and saw their potential time-saving effects as his unique selling point. “What I found with most people who are interested in climbing Everest is that time was the bigger problem than money,” he says.

This year four climbers joined his €95,000 ($111,000) Flash expedition — two dentists and a solar energy company owner, as well as Wagner. All were successful.

Kenton Cool is among those who question the science behind the pre-acclimatisation method, but Furtenbach swears the tents mean that climbers are better rested and have more energy for the summit push. Wagner, who also trained inside a hypoxic tent at his gym, said he had never felt so strong at altitude.

The 7 Summits Club also managed a 100 per cent success rate, meaning 59 people reaching the top in total, including the nine premium clients who paid $80,000 rather than $65,000 for the standard package. As well as the extra Sherpa support, good food and massages, at Tibetan base camp they enjoyed sofas, TVs, hot showers and a full bar — great for marketing, but shouldn’t climbing the world’s highest mountain require a commitment of time, and a tolerance of discomfort? “No,” says Alex Abramov, an experienced mountaineer and president of 7 Summits Club. “If people don’t have all these things, they become bored and want to go home. If the expedition is comfortable, more people reach the summit . . . We are humans, not yaks”.

Even old hands are sanguine about the evolution of Everest as a premium experience. Sir Chris Bonington climbed the peak in 1985, when Nepal allowed only one expedition per route each year. “I just thank God that I managed to climb it when I did,” he says, “but for the person who wants to do it today, it will be one of the great moments in their life, so why deny them that?”. He points out that expeditions were supported by armies of porters in his day, and that he and his team feasted in a large mess tent at base camp. To which Cool adds: “On the early British expeditions in the 1920s, they had copious amounts of foie gras and champagne. Being comfortable at base camp doesn’t necessarily detract from the experience. And you’ve still got to climb the mountain. Nobody can carry you up it.”

Crowds have been blamed for adding extra risk to expeditions, and budget trips often include minimally trained guides and Sherpas. Alan Arnette, an American climber and respected online Everest chronicler, says that premium packages, while still in the minority, can only be safer. Typically six to eight people die each year, a number that has remained steady in the modern era despite growth in traffic on the mountain, including less experienced climbers (around 100 people reached the summit each year in the early 2000s). “So many of the unknowns have gone, it’s no longer an exploration like it was 50 years ago,” Arnette adds.

What next for the premium package? Abramov has already ordered the construction of new luxury bathing houses and a new kitchen to be trucked to the Tibetan camp in time for next season. There are signs of increased comfort at the higher camps too. Furtenbach, who installed a sauna in a converted ski-lift gondola at base camp this year, already also provides a heated dining tent at Camp 1 (7,000 metres). He thinks others will follow, and that the era of longer expeditions is over. “I’m absolutely sure that in five or 10 years nobody will take two months to climb an 8,000-metre peak,” he adds.

Wagner is back at work now, and no longer sleeping in an altitude tent. Dismissing criticism of his approach to Everest, he says only one person can claim to have undertaken an entirely pure ascent: in 1996 the Swedish climber Göran Kropp cycled 8,000 miles from his home to base camp before climbing solo without supplemental oxygen. “Everyone else is in a grey area, and it’s not like I took the elevator,” Wagner adds. “I just chose a way to cut out the boring empty part.” At the summit, meanwhile, everyone is equal. “It’s an epic moment, knowing that this is the highest point in the world,” the climber adds. “Everything else is forgotten.”

Follow @FTLifeArts on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Subscribe to FT Life on YouTube for the latest FT Weekend videos

Comments