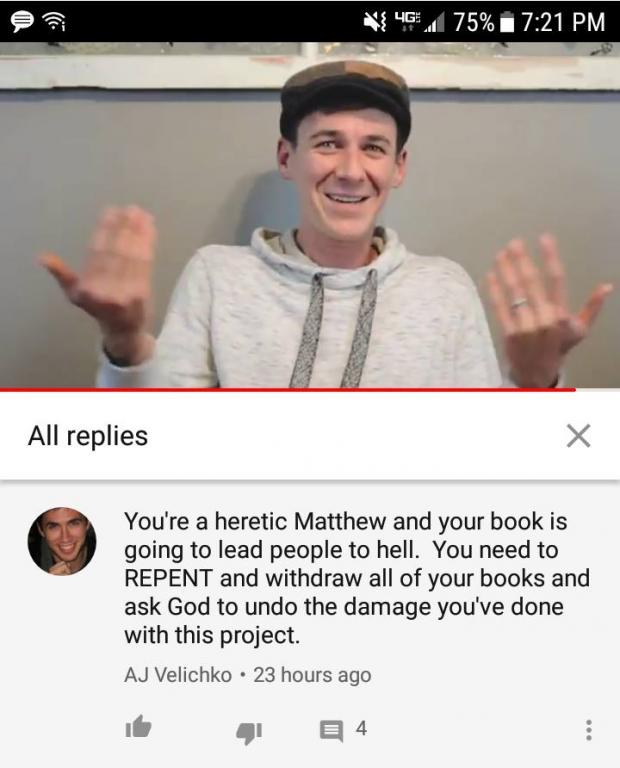

Being called a heretic is not something I relish. It can be humorous, sure. But, for the most part, it’s nothing more than an annoying distraction that offers zero meat to the conversation. Take, for instance, what YouTube commenter—and all around super-Christian, I’m sure—AJ Velichko recently said about my latest book:

“You’re a heretic Matthew and your book is going to lead people to hell. You need to REPENT and withdraw all of your books and ask God to undo the damage you’ve done with this project.”

Honestly, does this person really think that I have the power to lead people to hell? Or that I’m going to call up Amazon and have them pull all of my books? Get a grip!

Nevertheless, this attitude of vain arrogance is unfortunately what so much of Christianity has embraced. Without even really understanding the ancient heresies, many are simply stuck in the mindset that they have a monopoly on correct beliefs and that anything that pushes against their current theological box must be wrong, or worse, heretical, or even worse, something that will actually doom others to an eternal torture chamber.

Back in the day, however, this wasn’t so. Sure, as the Church progressed throughout history, certain doctrines were declared heretical. But they were done so with care. There were grand debates about doctrinal matters, and there were some valid reasons for deciding what was and what was not heretical. Agree or disagree on what the Church decided, but at minimum, admit that they weren’t as flippant as we are today.

So, with that said, I wanted to take a few moments to talk about 4 heresies that, in the eyes of the early Church, really weren’t heretical. I chose these 4 because they are the ones most commonly flung my way.

-

Affirming Universal Reconciliation

This is the big one for most heresy hunters. And I get it. Most of us grew up hearing that much of humanity would one day burn forever in hell. The problem, then, is that this isn’t what much of the early Church concluded. As Augustine once noted, “indeed very many” rejected the eternal punishment of the damned. And he wasn’t even a Universalist. Far from it!

Now, I will admit that sometime after Augustine—a couple hundred years in fact—Universalism was declared heretical. (But even then, it wasn’t so much Universalism per se, but some of the other ideas that were attached to it, namely Origen’s idea that souls were preexistent, that they “fell” into a human body, and that the Resurrection was merely a spiritual one.) And so, all this raises the question: Why did it take the Church so long to denounce what many today think is so clear? And why don’t any of the earliest creeds make any mention of hell? And why was Gregory of Nyssa, the final editor of the Nicene Creed, never condemned?

It certainly makes one wonder.

-

Rejecting Inerrancy

This one makes me chuckle a bit. Why? Because biblical inerrancy isn’t even a concept until well over 1,000 years after the life of Jesus. Sure, in many Protestant traditions, it is a stalwart of the faith. And that’s fine. They can have it. But it’s beyond ridiculous to suggest that those who deny it are heretics. You’ll more than struggle to find anything in the writings of the early Church that suggest such a ludicrous thing. And no, consulting the Westminster Confession of Faith or the Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy doesn’t count.

-

Affirming a Nonviolent God

This is another one that confounds me. But it’s one I come up against quite often. It goes a little something like this:

Me: God is just like the nonviolent Jesus.

Joe Christian: Sounds like Marcionism to me!

Me: [perplexed]

To contextualize this, allow me to briefly mention what Marcion believed. First, he thought that the violent God of the Old Testament was different from the nonviolent God of the New. Second, he believed that the entirety of the Old Testament, as well as some of the New, should be completely tossed out. And third, he believed that the created “flesh order” was bad, while the “spirit order” was good.

I affirm none of these things. Sure, I find some of the depictions of God found in the Old Testament to be problematic. I even go so far as to out-and-out reject—or allegorize—some of them. But that doesn’t mean I’m a Marcionite for doing so. In fact, it’s actually quite Orthodox. Second, I don’t toss out the Old Testament. Rather, I interpret it through the lens of the crucified Christ. Again, not very Marcionite of me. And third, per my mind, there is no such thing as a division between flesh and spirit in the way Marcion believed. (God is the God of all, no?)

To that end, if you want to call Marcionism heretical, go for it. You’d be accurate to do so. Just don’t conflate every nonviolent theology with the God of Marcion. You’d be dead wrong to do so.

-

Rejecting Penal Substitution

I harp on this all the time, but it bears repeating. Rejecting Penal Substitutionary Atonement theory is NOT heretical. How can it be? It wasn’t even a formally developed theory until the days of John Calvin. Sure, there are some writings from the early Church that use substitutionary language, but so what? There is nothing, so far as I know, in the writings of the early Church that says one must affirm this understanding of the cross. Again, how could there be? So, if you want to affirm it, affirm it. Just do yourself a favor and listen to those voices who disagree. Or, at least don’t anachronistically declare us heretics for disagreeing.

At the end of the day, it would be wise for us to slow our roll when it comes to denouncing others as heretics. Not only has such behavior divided the Church—how many denominations are there again?—but it has led to actual people being literally burned at the stake. Talk about bringing hell to earth! Can we afford to be such violent zealots any longer? I don’t think so. But I’m sure we’ll keep trying. Sadly.

Peace.