Donald Trump’s impeachment crisis may be China’s latest stroke of luck, blunting the US’ most serious challenge to its rise

- Since 1989, the US has repeatedly tried to put pressure on China, only to back down for political reasons

- Trump’s challenge to China has surpassed his predecessors’, but his Ukraine scandal may bring it to an early end too

It seems implausible that China can benefit from this development, not least since Foreign Minister Wang Yi has publicly reiterated Beijing’s commitment to non-interference in other states’ internal affairs. But over the last three decades, China has benefited from a string of remarkable lucky breaks.

In repeated crises since 1989, Beijing has simply held the line and developments have turned in their favour.

When it was clear that the party was not going to budge, the sanctioning states simply did not have the stomach for a drawn-out conflict in which they sacrificed their economic interests for the abstract goal of a more liberal and democratic China.

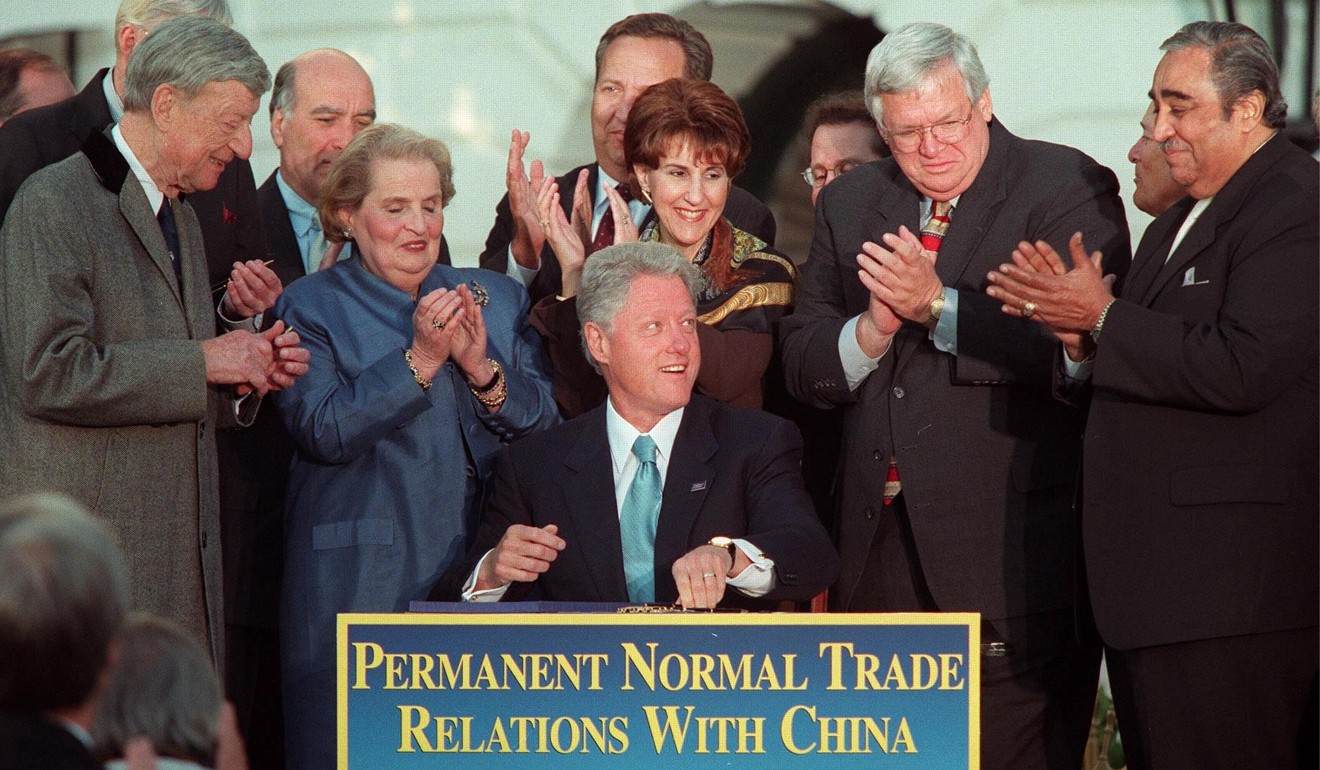

In May 1993, the administration of Bill Clinton established a policy linking the granting of US “most favoured nation” trade status to improvements in China’s human rights practices.

The Chinese leadership understood correctly that conceding to the US would severely threaten the party’s legitimacy, very possibly precipitating further challenges. They refused to make any meaningful concessions.

Four reasons Beijing will never cave in to Hong Kong protesters’ demands

Facing midterm elections in 1994, Clinton blinked. In a humiliating move, the link between human rights and the most-favoured-nation status was dropped.

The first months of the George W. Bush administration were equally fortuitous for China.

Taking aim at Clinton's second-term pro-engagement China policy, Bush declared on the campaign trail that China was a “strategic competitor”, a direct contrast to the Clinton administration’s characterisation of that country as a “strategic partner”.

Once in office, the Bush administration subjected China’s domestic and foreign policies to unflattering scrutiny.

China and the US, 40 years on: it’s complicated, but they’re still talking

China’s response was to precipitate the EP-3 crisis of April 1, 2001, where a US reconnaissance aircraft was coerced into landing on Hainan Island in China.

In the aftermath of the incident, a Pentagon official declared that ‘“it is not business as usual [in US relations] with China”.

Lady Luck shone again on China. The September 11, 2001, attacks established a compelling reason for Washington to put aside its emerging rivalry with Beijing for the sake of prosecuting the global war on terror.

Which brings us to the Trump impeachment issue and its relationship to the current crisis in US-China relations.

In an interview to introduce the administration’s December 2017 national security strategy, the then national security adviser H.R. McMaster commented that China was a “revisionist power” that was “undermining the international order”.

The report grouped China and Russia together as “revisionist powers”. The three previous national security strategy reports (in 2002, 2010 and 2015), while critical of aspects of Chinese policy, had not adopted such stark language.

Unlike the Obama administration, the Trump administration appears not prepared to compartmentalise issues.

Democratic trade hawks may mean big trouble for China – and Trump

The impeachment crisis comes at a particularly sensitive phase in the US-China negotiations on Beijing’s economic practices. Unless a deal is successfully brokered, US$550 billion in Chinese exports to the US will remain subject to tariffs.

Could the Trump impeachment saga be yet another instance where a totally unanticipated development occurs to China's potential benefit?

We simply do not know at this stage. But we can be sure that the Chinese leadership will be watching the development of the impeachment proceedings closely to see if their fortuitous winning streak continues.

Nicholas Khoo is an associate professor in the Department of Politics at the University of Otago, New Zealand. He is author of the forthcoming book Return to Power: China and East Asia since 1978