The first day I was in Shiprock, New Mexico, a horse made the front page of the local newspaper. The dark bay with a white stripe down its nose had fallen in a field outside town. The article's accompanying photo showed the animal’s leg twisted at a startling angle, the white of the bone poking through its torn skin. Locals called animal control, asking someone to put the horse out of its misery, but the county couldn’t do anything: It had fallen on Navajo reservation land, and tribal police officers had jurisdiction over the area. The animal languished in the field, in obvious pain, as residents of the area tried to figure out who could legally perform a mercy killing. When tribal police arrived (they’d had a higher-priority call, they told the reporter), they couldn’t find the horse. The county sheriff started to get blustery. “Enough was enough,” he said. Even if it wasn’t technically his responsibility, he couldn’t allow the animal's suffering to continue.

Finally, five days after the horse was first reported, a sheriff’s deputy drove out to euthanize the injured animal. Right then, a tribal officer pulled up, too. They dragged the horse to a nearby ditch, where the tribal officer shot it in the head. The director of animal control was livid. “This animal had to suffer for five days,” she told the paper, “because of jurisdictional issues.”

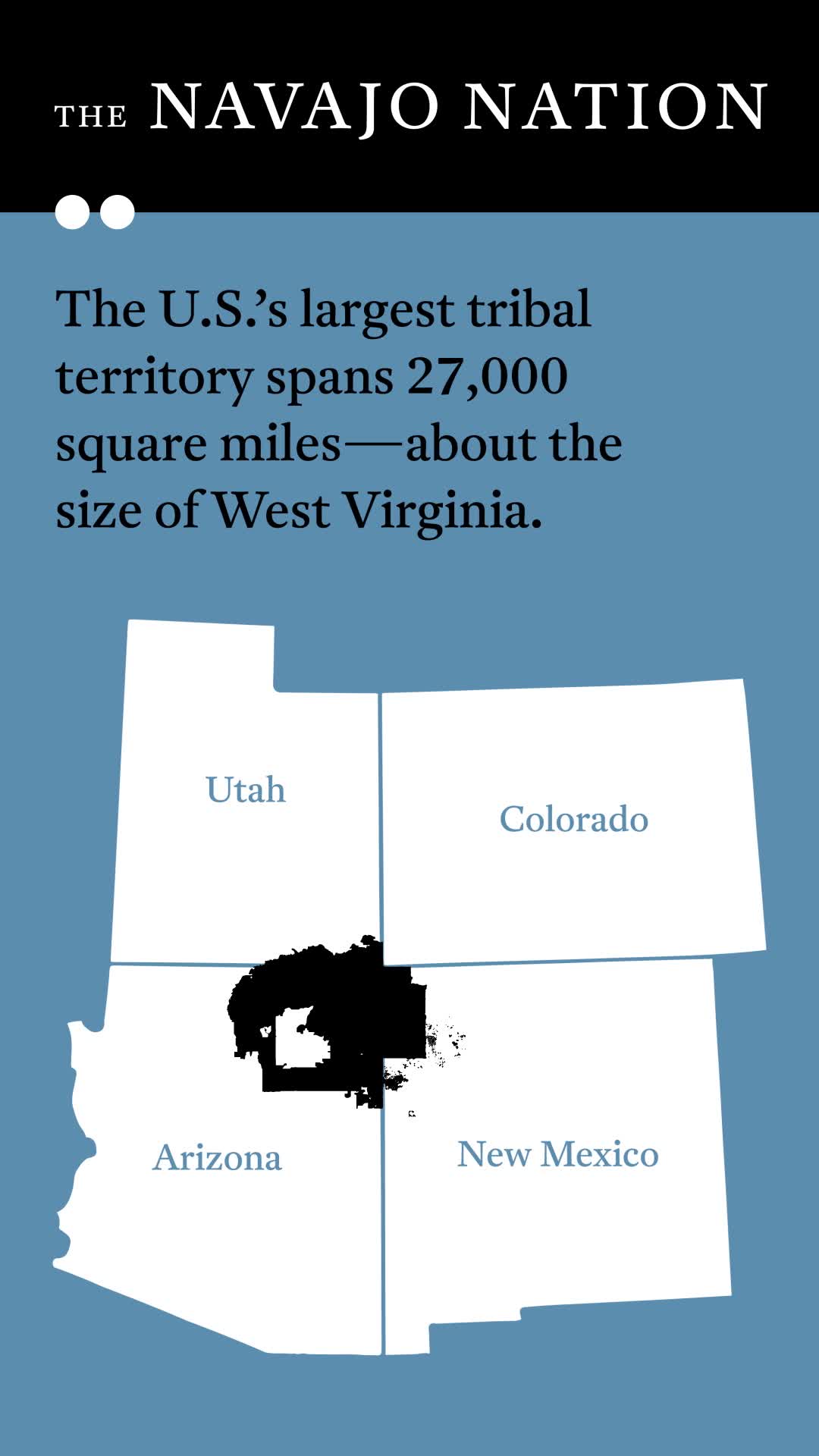

I thought about the bureaucratic banality of that phrase—jurisdictional issues—and the gruesome reality it glossed over as I drove through Shiprock, a town of around 8,000 people located on the Navajo reservation. Spanning twenty-seven thousand square miles across New Mexico, Utah, and Arizona, it’s an area of strip-mall churches, roadside sagebrush, and billboards warning kids about the dangers of meth. The town itself is named after the Shiprock Pinnacle, an otherworldly volcanic-rock formation that juts up about fifteen hundred feet from the desert floor. Nineteenth-century explorers thought it looked like a clipper ship. To the Diné, or Navajo, it is known as Tsé Bitʼaʼí, or “rock with wings,” and is considered a sacred site. During my time in Shiprock, the pinnacle loomed in the distance, marking the horizon, like an idea I couldn’t get out of my head.

I was in Shiprock because, a few weeks earlier, two children had gone missing from the Navajo reservation. One was later found dead a few miles south of the Shiprock Pinnacle. Or, if you wanted to put it another way: I was in Shiprock because of jurisdictional issues.

Just after school let out on the afternoon of May 2, 2016, a man in a red van cruised the rutted dirt roads of Shiprock’s Fruitland neighborhood. He was young and stocky, with squinty eyes. He pulled up alongside twelve-year-old Gracelynne Mike and asked if she needed a ride. When Gracelynne said no, the man drove farther down the road, out of Gracelynne’s sight, where her two siblings, eleven-year-old Ashlynne and nine-year-old Ian, were playing in a canal near a school bus stop.

This time, when the man asked, the children got in the car, with Ashlynne in the front seat and Ian in the back. As the red van headed in the opposite direction of their house, the kids grew nervous. Ashlynne reached back and clasped her brother’s hand. They were miles away from their home when the man steered off the highway and onto a dirt road, just south of the Shiprock Pinnacle.

When Ashlynne and Ian didn’t return home from school, Gracelynne felt anxious, then panicked. She thought about that red van. Her father, Gary Mike, was busy at work, so she called her mother, Pamela Foster, who lived in Redlands, California. Foster immediately called the Navajo Nation Police Department in Shiprock and told them that her kids were missing. “They kept putting me on hold and transferring me, telling me that they were short on staff, that there was only one officer on duty at Shiprock,” Foster told me. Frustrated and desperate, Foster posted on Facebook about Ian, Ashlynne, and the mysterious van.

At 6:53 P.M., Gary Mike filed a missing-persons report for his children with the Shiprock Police Department. Twenty minutes later, a couple driving through the Navajo reservation saw a young boy walking alone on the side of the road. When they pulled over, it was clear that he was frightened. They couldn’t get a cell-phone signal to dial 911, so instead they drove him to the closest Navajo Nation Police Department branch in Shiprock.

Police officers are trained to respond swiftly to reported abductions—to coordinate with other local law enforcement, to launch search parties, and to share information. But from what Ashlynne’s relatives could see, that didn’t seem to be happening in Shiprock. A little before 8 P.M., Mabelene Buck, Foster’s cousin, called the city police department in nearby Farmington, New Mexico. “My cousin just posted on Facebook that her kids were kidnapped,” Buck told the dispatcher. “I was just calling to see if the Navajo PD alerted you guys. Apparently they found my nephew—he escaped from that van—but they still have my niece.”

No, they didn’t know anything about a kidnapping in Shiprock, the Farmington dispatcher said. Buck let out a sigh of exasperation. "I can't believe they can't even..." she said, then hung up. Half an hour later, she called back. Ashlynne was still missing, had now been missing for hours, and it felt like nothing was happening. “Did you report this to the reservation police yet?” the dispatcher asked. Yes, Buck said. “They haven’t sent an Amber Alert or anything out, and I’m pretty much frustrated,” she said. Later that night, Buck went in person to the Farmington Police Department. A search team was ready to go, she says. “They said, 'We have everybody on standby here, we’re just waiting to hear an okay from the Navajo Nation since it’s a jurisdiction issue,'” she told me. “They couldn’t really do anything, and time was just ticking."

Meanwhile, as news of Ashlynne’s abduction spread through texts and phone calls and Facebook posts, the Shiprock community, accustomed to delayed responses from law enforcement, sprang into action. Friends and family members mobilized an ad hoc search party. Gary Mike drove the roads near the Shiprock Pinnacle, trying to interpret Ian’s patchy memories—there had been cows to the left of him, houses to the right, horses in front—before the setting sun made the search more difficult. Even after night fell, Gary kept searching, ragged with panic, illuminating little patches of dirt with the flashlight on his phone. In Shiprock, Rick Nez, president of one of the local Navajo Nation chapters, transformed the chapter house—essentially the equivalent of city hall—into an informal command post, stockpiling bottled water and organizing search parties. In California, Foster wept at the thought of her daughter out in the desert, alone.

As the night wore on, Ashlynne’s relatives continued to call the Farmington police and ask why an Amber Alert hadn’t been issued. “I was waiting for it to come through on my phone,” one said, “and we haven’t got anything yet.”

It wasn't until 9:07 P.M. that the Navajo Nation Police Department finally requested an Amber Alert from the Federal Bureau of Investigation. However, Amber Alerts are typically initiated by state police, not the FBI. The lack of clarity about who was supposed to set the alert in motion meant that—for several crucial hours—no such process was taking place. Sometime after midnight, an FBI agent contacted the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children. They, in turn, contacted the New Mexico State Police, formally launching the Amber Alert process.

When Nez finally made it home that night, his wife couldn’t stop talking about Ashlynne. Sweet little girl, she said. She’s so petite. She’s so small. Hours later, they were jolted awake by the simultaneous buzzing of their cell phones. The automated text message informed them that an Amber Alert had been issued for Ashlynne Mike. It was 2:30 A.M., eight hours after Gary Mike had first reported that his children were missing.

Three weeks before the red van slowed to a stop by Ashlynne and Ian Mike, Jim Walters, a good-natured Texan with a bristly mustache, sat in a Taos, New Mexico, conference room, where he was surrounded by tribal police chiefs and others working on the front lines of child abductions in Indian Country (federal parlance for the fifty-six million acres of the United States controlled by 567 different federally recognized native groups). They’d convened to discuss the many ways abduction investigations can go awry on reservations.

Two constants had defined Walters’s career as a detective. One was working and living on tribal lands. The other was child abduction. Early on, Walters worked a kidnapping case that ended in a cross-country pursuit and the successful return of three children; it also resulted in Walters becoming something of a child-abduction specialist. “Once you understand that stuff, the cases start coming to you,” he told me.

In 1996, U.S. law enforcement’s response to child abductions transformed when a nine-year-old girl named Amber Hagerman went out for a bike ride in Arlington, Texas, and never came home. The scope and urgency of the case overwhelmed the small city’s police department. Five days later, Hagerman’s body was found in a nearby creek; pathologists reportedly estimated that she had been kept alive for two days. Her murder—still unsolved—inspired the creation of the Amber Alert system, visible to most of us as those notifications about missing children that arrive as text messages or are displayed on electronic-message highway signs. Over the course of its existence, the Amber Alert program has been credited with the safe recovery of 897 children.

Behind the scenes, the Amber Alert program trains police departments to respond quickly and efficiently when children are kidnapped. Time is of the essence: in child abduction cases that end in homicide, 76 percent of those kidnapped are killed within three hours of their capture. And communication between different law enforcement groups, who must collaborate quickly on a search, can mean the difference between life and death.

But quick and effective responses are particularly challenging on tribal lands, where jurisdictional issues, economic disparity, remote locations, and a long-standing mistrust of law enforcement come into play. Over the years, the problem gnawed at Walters—how decades of disenfranchisement meant that many tribal areas didn’t have the authority, means, or expertise to handle child abductions. “If your child got abducted in Albuquerque, you got all the resources of the Amber [Alert] program,” he told me. “But if your child was abducted on the Navajo reservation, there was basically nothing there."

In 2006, the Department of Justice asked Walters to help run a new initiative, called Amber Alert in Indian Country. A year later, Walters and his team launched ten pilot programs, including one on the Navajo Nation. The Nation received a $330,000 federal grant to get the program up and running, and nominated a Navajo police captain as the Amber Alert coordinator. But he was out within three years, and no one was hired to replace him. The tribal council was unable to pass the required resolution in time to keep the program going, and half of the grant money was returned to the federal government.

In Taos, Walters seemed pained as he discussed the slow-motion disintegration of the Navajo Nation’s Amber Alert program. Its dwindling was tied to larger issues facing tribal law enforcement: How chronic underfunding left some 911 operators in tribal areas taking notes on yellow legal pads and transmitting emergency calls off a mobile radio. How tribal police departments are often understaffed yet responsible for huge swaths of land. How tribal police are paid less than other law enforcement, which leads to low morale, high turnover, and disputes with other agencies. How high turnover means it’s hard to make training stick. How there simply aren’t enough people to train. “Fort Peck [on the Sioux reservation in Montana] hasn’t had a police chief in five or six years,” Walters told the room. “There’s a chronic staffing shortage.” The tribal police chiefs shared stories of county sheriffs who refused to cooperate with their tribal counterparts, whether due to racism, or territoriality, or a complicated mix of both.

Many of these problems trace back to the fundamentally vexed relationship between indigenous groups and federal and state governments. While tribal nations are ostensibly sovereign, with their own justice systems, their ability to conduct proceedings and levy punishments is limited. When major crimes are committed on tribal lands, the Bureau of Indian Affairs or FBI steps in to run the investigation, and the U.S. attorney's office brings charges. Or doesn’t: According to a 2010 report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office, the U.S. attorney's office declined to prosecute two-thirds of sexual-assault cases referred to it by tribal governments.

And so the people gathered in Taos were left to grapple with the pervasive sense of futility and despair at U.S. law enforcement’s ability to do much of anything useful in Indian Country. Kevin Mariano, chief of police in the Isleta Pueblo, a tribal area south of Albuquerque, told a story about a man who had allegedly committed multiple sexual assaults on tribal lands. “Each time, it didn’t get picked up by federal court,” he said. “Eventually someone went and burned the guy’s house down.”

While sexual assaults on tribal lands are notoriously difficult to investigate and prosecute, child abductions come with their own set of challenges. The various bureaucracies of individual states muddy the issue even further. Almost everywhere in the U.S., potential Amber Alerts are vetted and issued by state authorities, which keeps your phone from being flooded with mistaken or incorrect alerts. This is further complicated on reservations, as under-resourced tribal police officers search for the missing while simultaneously coordinating with state police to issue an alert—sometimes across multiple state lines.

Then, of course, there’s the legacy of mistrust between people living on tribal land and law enforcement, one that stretches back centuries, and is still deeply visceral. (Native Americans are more likely to be killed at higher rates by police, per capita, than any other group, including African-Americans.) “We talk about generational trauma,” Walters told me. “It’s absolutely the reality.”

In tribal areas, Mariano noted at the meeting, the abduction-prevention strategies that law enforcement rely on—things like training exercises and information sessions—can backfire. Traditional taboos are still strong among some elders. “They don’t wish [abductions] to happen, which is why they don’t want you to have these [training] exercises,” he said. He’d worked in law enforcement for a long time, but sometimes he felt caught between his role as a cop and what he’d learned from his grandmother: that openly talking about issues like child abuse and kidnapping invites those evils into your community.

Three weeks after I left Taos, Walters called to tell me the news from Shiprock. I was too shocked to respond at first. We’d talked about abductions, and then an abduction had happened. “It’s hitting Mariano hard,” Walters said, “because of what he said in the meeting.” It felt like a horrifying manifestation of the problems we’d discussed in Taos—as if we’d been talking about the red van before we even knew it existed.

The day after Ashlynne’s abduction, a half-dozen men from the Native American Church gathered for a ceremony in a small sweat lodge, including a relatively new member of the community, Tom Begaye. Begaye’s parents had attended the church before they died, leaving Begaye to care for his younger brother. A year prior, in 2015, a church member discovered the brothers living in a filthy trailer, subsisting primarily on a diet of breakfast cereal. It was clear they’d had rough lives marked by abuse and neglect. The church's community took the boys in and were encouraged to see them slowly open up.

But on this morning, Ashlynne, the quiet girl whom several considered a cousin, was the focus of everyone’s thoughts. The men sat in the steam, singing and praying for her safe return.

Partway through the ceremony, they heard voices shouting outside. Someone within the lodge pushed open the heavy flap, and the men stumbled out, shirtless and shiny with sweat. When the cloud of steam cleared, they saw a line of black cars and men pointing guns at them. Ashlynne Mike’s body had been found that morning, and Tom Begaye, who had just been praying for Ashlynne, was arrested for her murder.

After his arrest, Begaye was in something of a dissociative state, his attorney said later, and was unable to comprehend the enormity of his crimes. He confessed to investigators that he had abducted the children, that he had driven them to a remote area near the Shiprock Pinnacle, that he had raped Ashlynne, that he had hit her with a tire iron because he was ashamed and didn’t want anyone to know what he had done, and that he had left Ian behind in the desert. He also said that Ashlynne was still moving when he drove away that afternoon.

This may have been a morbid kind of wishful thinking on Begaye’s part, or a refusal to admit that he had actually committed murder. But it haunted everyone who knew Ashlynne. If the Amber Alert had been issued sooner, if the search had been marshaled more quickly, could she have been found, and saved?

On my second day in Shiprock, I met Gary Mike off Navajo Highway 36, at mile marker thirteen. It was the easiest place to meet an outsider unfamiliar with the town’s maze of unnamed, unpaved dirt roads and unnumbered houses. It was also where first responders had congregated on the night of Ashlynne’s abduction. In the weeks since, it had transformed into a roadside memorial.

Mike wanted me to show up at precisely 6:30 P.M.—the time he’d first reported his kids missing to the police—so I could see just how much daylight remained, and how much time there had been that night to locate Ashlynne.

Mike is a soft-spoken man who wears his long hair loose. All of the attention and publicity around the case, and the fact that his mourning had to be performed publicly, had been hard on him. Even so, he was unfailingly polite as he told me the story of his daughter’s abduction and murder: how everyone seemed to move so agonizingly slowly, and how he’d had to help the FBI agents figure out how to locate the Native American Church’s sweat lodge on Google Earth. (“I finally said, Scoot over,” he said, an edge creeping into his steady voice. “Well, I was more polite than that.”)

As Mike spoke, I felt acutely aware of the day’s slow slide into twilight. When he finished talking, it was late enough that I could no longer make out the memorial’s colorful jumble of balloons and posters and teddy bears. Mike looked out into the night. “It might have been a whole different story,” he said.

Over the next week, each time I stopped by the roadside memorial, there were different visitors—a couple from Gallup, a family from Farmington—who hadn’t known Ashlynne, but who wanted to honor her nonetheless. Members of the Navajo Nation were particularly troubled that the man who had killed her was a part of their own community. That the murder had taken place at a sacred site, and that the murderer went to a sweat lodge ceremony immediately afterward, was almost too much to bear. Instead, the community focused much of its anger on the issue of the delayed Amber Alert. "Why is it that they're not snapping their fingers, you know, and saying, 'A child is missing. Okay, let's go'?" one of Ashlynne’s relatives told CBS News. "This is something that for them—the Navajo police—is a wake-up call."

In the days and weeks after Ashlynne’s death, the finger-pointing began. “We do not know why the Amber Alert was not done until early that morning,” Navajo Nation Police Captain Ivan Tsosie, the acting police chief in Shiprock at the time of the abduction, told the Farmington Daily Times. "You would have to contact NDCI [the Navajo Department of Criminal Investigations] and FBI to answer that question." Navajo Nation President Russell Begaye (no relation to Tom Begaye) told me that Captain Tsosie “has the responsibility. Making excuses is trying to get off the hook.” (Tsosie was reportedly later placed on administrative leave, and the Navajo Nation Police Department did not respond to repeated requests for comment.) But the Nation's top public-safety official, Jesse Delmar, disagreed that any mistakes had been made: “There is a protocol and process in place,” he said in a statement, “[and] everything was handled according to the protocol."

Two weeks after Ashlynne’s death, the New Mexico State Police sent an email to the FBI, the tribal police, and every law enforcement agency in the state, reminding them of the proper process for issuing Amber Alerts: The responding agency confirms that the abduction meets the Amber Alert criteria and then contacts the state. The email stressed that time was “of critical importance” in abduction cases: “It takes considerable time enough on our part (approximately a 40 minute process) to ensure the [Amber Alert process] is carried out, so it is crucial that NMSP be notified as quickly as possible in the early stages of the investigation,” it read.

“When the process is followed, the system works,” Sergeant Chad Pierce, spokesperson for the New Mexico State Police, told me. The implication seemed clear: When the process isn’t followed, all bets are off.

Local leaders differed on what had gone wrong. Rick Nez, the chapter president who helped mobilize the community in the wake of the abduction, felt the ineffective response was indicative of a larger tendency within his community toward leniency. What tribal lands needed, Nez believed, was more law and order. “People want to let things be as they are, but we can no longer do that,” Nez told me. “We have to encourage other communities to identify sex offenders. We need street names, we need house numbers. We’re so good about saying we’re a sovereign nation, yet we don’t follow up on certain things. This should be a lesson to the Navajo Nation: This is the time not to falter, but to strengthen laws.”

This sentiment was echoed both within and outside the community. New Mexico Governor Susana Martinez cited Ashlynne’s death as a reason to bring back the death penalty in New Mexico, while Pamela Foster, Ashlynne’s mother, circulated a petition asking the Navajo Nation to reconsider its anti-death-penalty position. “The Laws in our Criminal Justice System on the reservation need to change,” Foster wrote in her petition, specifically criticizing the traditional Navajo method of dispute resolution: “We need to step away from hozhooji naat'aanii, ‘talking things out in a good way’ and let the Justice System take action in prosecuting criminals to the fullest extent.”

Except that working with the justice system—taking federal money for programs like Amber Alert and sex-offender registries—can come with strings attached, said Duane “Chili” Yazzie, another local leader. Yazzie is a longtime radical activist who first became prominent in the 1970s, when he played drums in the Native American band XIT and organized protest marches in Farmington after three Navajo men were murdered by white teenagers. Photographs and paintings of the Shiprock Pinnacle hang on every wall of his cluttered office. On the day we spoke, Yazzie wore a long string of red beads and a denim jacket with one sleeve pinned up; he’d lost his right arm in a 1978 assassination attempt.

Federal rules and regulations may contradict native culture and beliefs, and ultimately undermine tribal authority, he said. “With our cultural identity and our history, we have methods for how to deal with [these issues]—approaches based on methodologies that are culturally relevant. With alcoholism, for example, there are holistic treatments that don’t just treat the body. There are some of us who think that continuing to take money from the federal government makes us not as sovereign as we might be.”

Later, I spoke with Sarah Deer, a legal scholar who specializes in the intersection of federal Indian law and victims’ rights. “There are all these strings attached to some of the jurisdictional fixes, and they limit the opportunity of tribes to be creative,” she told me. “But violence against women and children is also a threat to our sovereignty. If 80 percent of your population is being victimized in some way, which is what the statistics indicate, then that is also a threat to self-government.”

During the month after Ashlynne’s death, Amber Alert experts traveled to the Navajo Nation twice to offer training sessions. According to an assessment by consultants for the Amber Alert program, dozens of people attended, but the vast majority were community members. In July, Amber Alert in Indian Country representatives returned to host a special session on leadership issues and the Amber Alert program. Only a handful of tribal police officers showed up, and the Navajo Nation’s newly minted Amber Alert coordinator—its first in six years—wasn’t there.

And then, over the summer, two young boys were abducted from a campground on the Navajo Nation near Wheatfields, Arizona.

After the much-criticized response to Ashlynne Mike’s abduction, this was the Nation’s chance to show it could act quickly. And this time, according to the assessment, the Navajo Nation Police Department didn’t wait for the FBI to request an alert for the missing children. But while the children were last seen in Arizona and heading east, the Nation requested an Amber Alert for Utah instead; they only had direct access to the tech network that initiates the alert system for Utah. On websleuths.com, a popular message board for real-time discussion of crime cases, commenters were puzzled: “What am I missing?” one asked. “The alert is issued for Utah, but the children were taken from Arizona.”

The children were found safe the next day, but the confused response made it clear there was more work to be done. To Jim Walters, it was increasingly obvious that the Navajo Nation—and tribal nations throughout the country—needed a process to issue an Amber Alert across the entire Nation, without the gatekeeping of the states. But making that a reality would require massive technology upgrades, more grant funding, trained dispatchers—and congressional approval.

Pamela Foster took up the issue, too. Foster had never considered herself a particularly political person, but after Ashlynne’s death, she began to share musings about justice on Facebook, alongside stories of her daughter. “My loss still evokes rage at the injustice of it all,” she wrote. Speaking out about abduction, sexual abuse, and threats against children ran counter to the messages she’d absorbed growing up, but writing about Ashlynne was like a form of therapy. Soon it also became a form of connection, as other people, mostly Navajo women, reached out to Foster to share their own accounts of trauma and abuse.

Foster wondered whether crimes against women and children didn’t get much traction in the Navajo Nation because men dominate tribal leadership. “The women kind of stay quiet,” she said. “A lot of people want changes, but they don’t want to stand up—a lot of them are in fear. I had to go beyond my boundaries.” Foster says no one from the Nation’s administration met with her after her daughter’s death, so she turned her attention to lobbying Congress.

Thanks in large part to urging by Foster and Jim Walters, last April John McCain introduced the AMBER Alert in Indian Country Act to provide more federal funding—and more federal oversight—for tribes to develop their own Amber Alert plans and to more easily coordinate with state programs. The bill would also mandate closer integration of state and tribal Amber Alert systems; for the Navajo Nation, the new law would mean that tribal police could activate an alert across the entire reservation. “We cannot allow reservations to become safe havens for criminals intent on harming children,” Senator McCain wrote in an email. “Our bipartisan bill will give tribes the resources they need to quickly issue AMBER Alerts, help victims escape tragedy, and save lives.”

Foster and Walters traveled to Washington last May to meet with members of Congress and drum up support for the bill. “I cried the whole time I was out there, because I kept telling my story to all the legislators,” Foster told me. “That was one of the hardest things to do. You have to relive it, and that brings with it so much pain. But I did it.”

This past November, the Senate unanimously passed S.772, the AMBER Alert in Indian Country Act. In February, the U.S. House of Representatives passed the bill, with one significant change: It was now named after Ashlynne Mike. On Friday, April 13, President Trump signed the bill into law.

If the bill is backed with robust funding and embraced by community leaders, then children who go missing on tribal lands will fare better than they might have before. But the Amber Alert in Indian Country system doesn't exist in a vacuum; it exists within the fraught legacy of colonialism. Those wounds are old, and deep, and still hurt today. They’re there in the despairing calls to emergency dispatch, in the Facebook posts, and in the yellow balloons at a roadside memorial. They’re the reason behind this imperfect patchwork system of overlapping tribal, state, and federal law enforcement agencies. It’s a system with many cracks, and it's often the most vulnerable people who fall through.

On a bright day last October, I sat in a silent courtroom in Albuquerque, waiting for Tom Begaye’s sentencing to begin. Begaye, wearing an orange jumpsuit with his hands, legs, and wrists shackled, sat in the front of the room, flanked by his attorneys. Ashlynne’s friends, family, and supporters filled the room. Nearly everyone was dressed in yellow, Ashlynne’s favorite color.

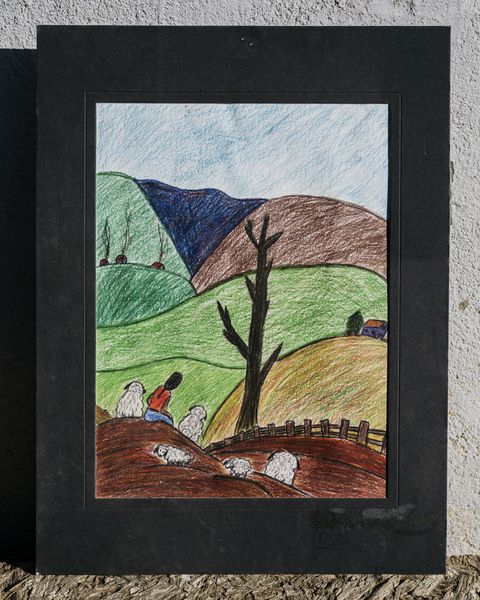

As we waited for the judge to enter, I thought about how one of the saddest, the most fundamentally unfair things about death is how it reduces and flattens a person. The TV news airs the same school photo over and over again. The newspapers repeat the same anecdotes. Being eleven is about being in flux, testing out what kind of person you want to be. Ashlynne Mike was now forever fixed as a girl who played the xylophone, a girl whose favorite color was yellow, a girl who was murdered. (When I’d met Gary Mike sixteen months earlier at Ashlynne’s roadside memorial—covered in yellow balloons, yellow ribbons, yellow flowers, yellow teddy bears—he said that in the weeks before her death, she’d decided her new favorite color was royal blue. “But yellow’s nice, too,” he’d said quietly.)

Ashlynne’s parents were given a chance to speak. Pamela Foster, wearing an embroidered yellow blouse, took nearly a minute to compose herself. “Of all the times I’ve had to speak,” she said, “this will be the hardest.” Her voice high with grief, Foster told the court that Ian missed how his sister used to run her fingers through his hair to help him fall asleep, and how Ashlynne’s friends and classmates remembered her as “fun, shy, sweet, happy, smart, kind, talented, an artist, and a great friend.”

James Loonam, Begaye’s public defender, stood and spoke briefly on his client’s behalf. He mentioned that Begaye was intellectually disabled, that he had suffered extreme abuse as a child and had been beaten in the head with a two-by-four. “He hopes,” Loonam concluded, “that the community he’s hurt so badly can find peace in making greater efforts to protect all children.” Then the judge sentenced Begaye to life in prison without the possibility of parole—a plea both sides had agreed to in advance. Ashlynne’s family walked outside to the courthouse steps and released dozens of balloons—gold, blue, purple. We all stood and watched as they took a long time to disappear into the wide New Mexico sky.