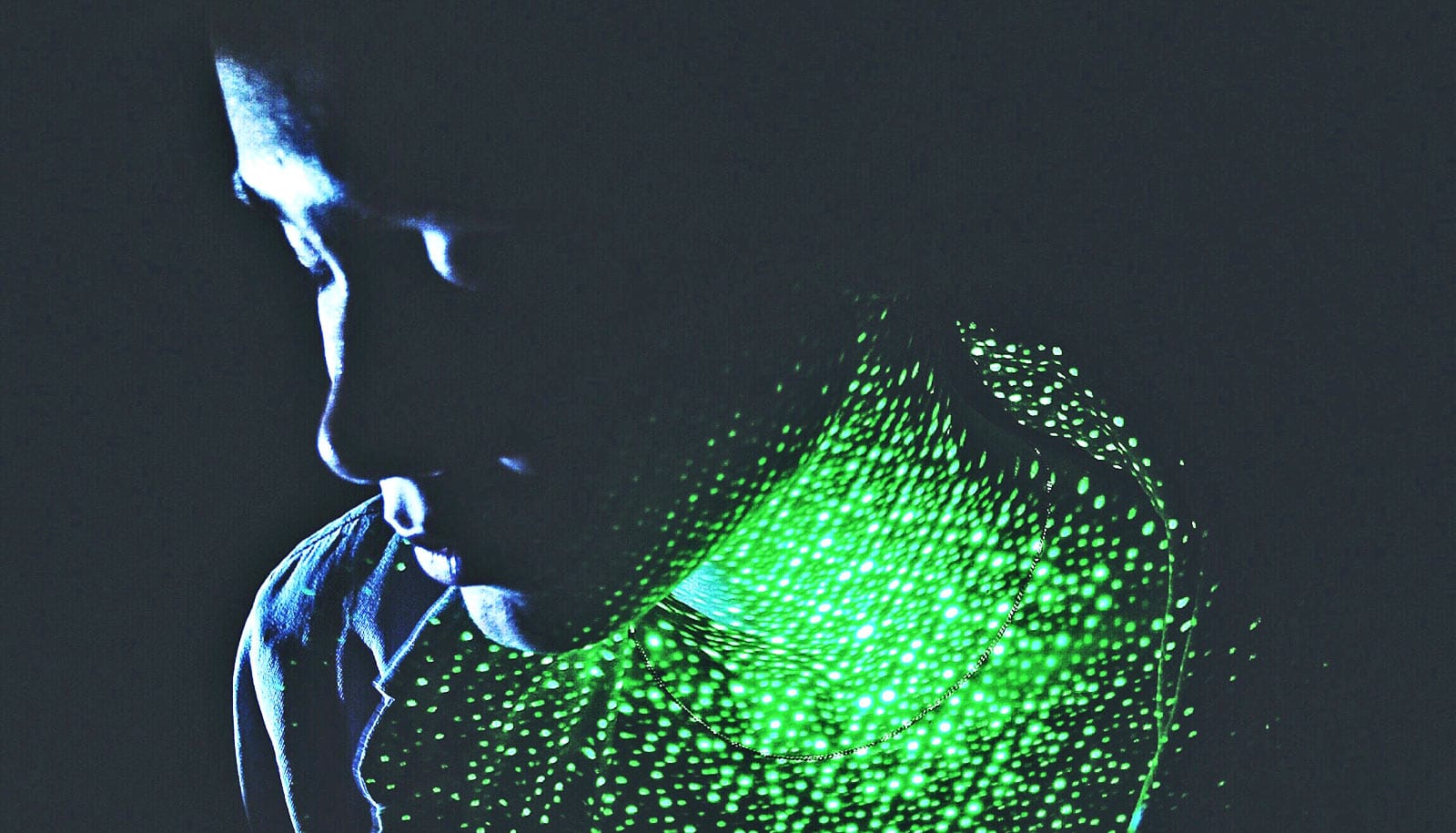

Although nanoparticles could have large untapped potential and new applications, they may also have unintended and harmful side effects, according to a new study.

Researchers found that cancer nanomedicine, designed to kill cancer cells, may accelerate metastasis. Processed food (e.g., food additives), consumer products (e.g., sunscreen), and even medicine contain nanoparticles.

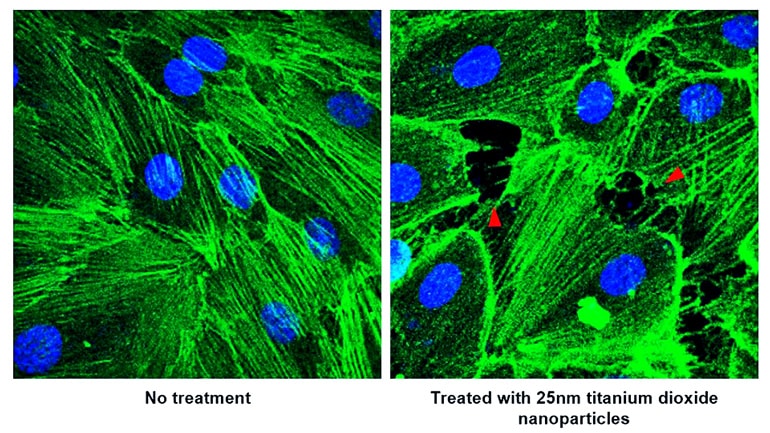

Using breast cancer as a model, they discovered that common nanoparticles made from gold, titanium dioxide, silver, and silicon dioxide—and also used in nanomedicines—widen the gap between blood vessel cells, making it easier for other cells, such as cancer cells, to go in and out of “leaky” blood vessels.

The phenomenon, which the researchers named “nanomaterials induced endothelial leakiness” (NanoEL), accelerates the movement of cancer cells from the primary tumor and also causes circulating cancer cells to escape from blood circulation. This results in faster establishment of a bigger secondary tumor site and initiates new secondary sites previously not accessible to cancer cells.

“For a cancer patient, the direct implication of our findings is that long term, pre-existing exposure to nanoparticles—for instance, through everyday products or environmental pollutants—may accelerate cancer progression, even when nanomedicine is not administered,” explains research co-leader David Leong, associate professor in the chemical and biomolecular engineering department at the National University of Singapore’s Faculty of Engineering.

“We need to tread this fine line very carefully and optimize the duration at which the tumors are exposed to the nanoparticles…”

“The interactions between these tiny nanomaterials and the biological systems in the body need to be taken into consideration during the design and development of cancer nanomedicine,” he adds. “It is crucial to ensure that the nanomaterial delivering the anti-cancer drug does not also unintentionally accelerate tumor progression. As new breakthroughs in nanomedicine unfold, we need to concurrently understand what causes these nanomaterials to trigger unexpected outcomes.”

Fortunately, the situation is not doom and gloom. The researchers are harnessing the NanoEL effect to design more effective therapies. For example, nanoparticles that induce NanoEL can potentially increase blood vessel leakiness, and in turn promote the access of drugs or repairing stem cells to diseased tissues that may not be originally accessible to therapy.

“We are currently exploring the use of the NanoEL effect to destroy immature tumors when there are little or no leaky blood vessels to deliver cancer drugs to the tumors. We need to tread this fine line very carefully and optimize the duration at which the tumors are exposed to the nanoparticles,” says Leong. “This could allow scientists to target the source of the disease, before the cancer cells spread and become a highly refractory problem.”

“Moving beyond cancer treatment, this phenomenon may also be exploited iassociate professor Ho Han Kiat, associate professor in the pharmacy department at the National University of Singapore Faculty of Science.

“For instance, organ injuries such as liver fibrosis may cause excessive scarring, resulting in a loss in leakiness which reduces the entry of nutrient supplies via the blood vessels. Both our research groups are now looking into leveraging the NanoEL effect to restore the intended blood flow across the scarred tissues.”

The study appears in the journal Nature Nanotechnology.

Source: National University of Singapore