Stephen Hawking Was Very Particular About His Tea

Despite physical limitations, the late scientist had a singular, stubborn insistence on living life on his own terms.

As a theoretical physicist who specializes in cosmology and gravitation, I naturally had many opportunities to interact with Stephen Hawking before his death. We attended the same physics conferences, where he was always rightfully celebrated as one of the world’s great scientists. He regularly visited the California Institute of Technology, where I work as a researcher. And, in perhaps my greatest contribution to world culture, I helped arrange Stephen’s cameo appearance on The Big Bang Theory.

But to get a glimpse of what Stephen was really like, let me tell you the story of time I picked him up at the airport.

Usually picking someone up at the airport is not a major logistical operation. Stephen, who lived with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or ALS, traveled with a retinue of students and nurses, as well as his custom-made wheelchair and various pieces of medical equipment. But this should have made my job easier, rather than harder: All I was actually asked to do was to meet them upon their arrival and point them toward the special van that had been rented for Stephen’s use. In-and-out job, right?

I should have known better. First, only one person in Stephen’s group, a graduate assistant, was licensed to drive the van, and that assistant was staying in a different hotel than Stephen and the nurses. But Stephen had a rule that the van was to be with him at all times, even if the person who was allowed to drive the van was elsewhere. And he wanted to check into his own hotel room, then proceed to dinner, before the graduate assistant checked into the other hotel. So I was asked to follow the group as they went to the first hotel and then to dinner, at which point I could take the assistant to his hotel and then back to rejoin the group at the restaurant.

All was proceeding more or less according to plan, but after checking into the hotel it was decided that they really should stop for some grocery shopping before heading to dinner. While parked at a local supermarket, a stream of nurses traveled between the van and the store, bringing various samples of tea bags for Stephen to choose from. Stephen, solid Englishman that he was, was very particular about his tea.

Eventually we were on our way to the restaurant. Following behind the van in my car, you could imagine my surprise when the van stopped dead in the middle of the road. It stayed that way for several minutes. This was in 1998, a time before everyone had cellphones, and I didn’t feel like getting out of the car in the midst of onrushing traffic, so I was stuck not understanding what was going on. Ultimately, the van started up again, performed a few turns, and ended up at the right place.

Only later was it explained to me what had happened. Stephen was the only one who actually knew where the restaurant was. At some point while the graduate assistant was driving, a single word of Stephen’s synthesized voice came from the back of the van: “No!” Apparently they had gone too far. It always took Stephen a long time to compose sentences on his computer, but eventually he was able to guide the driver back on course. Long past midnight, hours after they had landed, I was finally able to head to my own bed.

Stephen Hawking, despite an overwhelming physical disability, did not put his fate into the hands of others. He was in control; he was The Decider. None of his extraordinary characteristics—intelligence, charisma, humor, courage—might have amounted to much, if it weren’t for his singular, stubborn insistence on living life on his own terms.

This willfulness came through in his science, as well as in his everyday routine. Stephen gained fame not only through his insight and creativity, but by his willingness to stick his neck out and to swim against the tide. He frequently made bets with this fellow scientists, and very often took a contrarian position just for the fun of it. He bet that black holes didn’t exist and that we would never discover the Higgs boson, both wagers he was happy to eventually concede.

Stephen’s greatest discovery was, by his own account, initially motivated by pique at another physicist. Jacob Bekenstein, a young graduate student, had suggested that black holes have entropy, a way physicists have of measuring the disorderliness of a system. Stephen was annoyed by that, since he recognized that having entropy implied that a black hole should have a temperature, and therefore should emit a glow of radiation—and black holes didn’t do that, they were black! He set out to do a careful calculation to prove Bekenstein wrong, but what he ended up proving was the opposite: Black holes do have entropy, which we now call the Bekenstein-Hawking entropy. And they do give off radiation, which we call Hawking radiation. As he would later put it, “black holes ain’t so black.”

If he was fond of taking bold positions, Stephen was always more than willing to admit when he was wrong.

The existence of Hawking radiation led directly to a puzzle that still preoccupies theoretical physicists today: If the mass and energy that go into a black hole will eventually evaporate away, what happens to the information specifying the precise arrangement of whatever fell in? Ever since the time of Isaac Newton, most physicists have believed that conservation of information is a cherished principle of physics. If, in principle, you knew exactly the state of the universe today, you could predict what the state would be in the future, as well as what it had been in the past. Hawking radiation seems to overturn this idea, as whatever we use to make the black hole gets converted into the same bath of outgoing particles in the end.

Attempts to solve this puzzle have led to some way-out ideas. Just a few years ago, a group of physicists from the University of California, Santa Barbara, argued that if information really does escape from black holes, that implies a frightening consequence: Anyone falling into a black hole wouldn’t pass peacefully inside before eventually hitting a singularity, but would rather be incinerated by a high-energy wall of fire. This “firewall paradox” has ignited a new bout of attacks on Stephen’s original puzzle, inspiring speculative ideas about how quantum entanglement might be related to wormholes in space-time.

Stephen himself reveled in speculative ideas. Another of his major contributions was a proposal for the “wave function of the universe,” an attempt to encapsulate the exact quantum state of all of reality in a single, compact expression. Part of this work was the implication that the universe could have a beginning—presumably at the moment we think of as the Big Bang, about 14 billion years ago—without anything outside the universe bringing it into existence. Reality could be self-contained without violating the laws of nature. Stephen wasn’t afraid to leap from this cosmological scenario to the sweeping claim that God was no longer required to account for our existence. Bold proclamations were his stock in trade.

To a younger scientist, Stephen could be intimidating. Back when I picked him up at the airport, I was working as a postdoctoral researcher at the Kavli Institute for Theoretical Physics in Santa Barbara. His visit happened to coincide with the announcement that astronomers had shown that our universe was not only expanding, but accelerating—perhaps the most surprising cosmological discovery of our time. I happened to be an expert in the area, so I received a summons: Come down to Stephen’s office and explain what is going on. I did the best I could, offering long, rambling answers to his pithy, pointed questions.

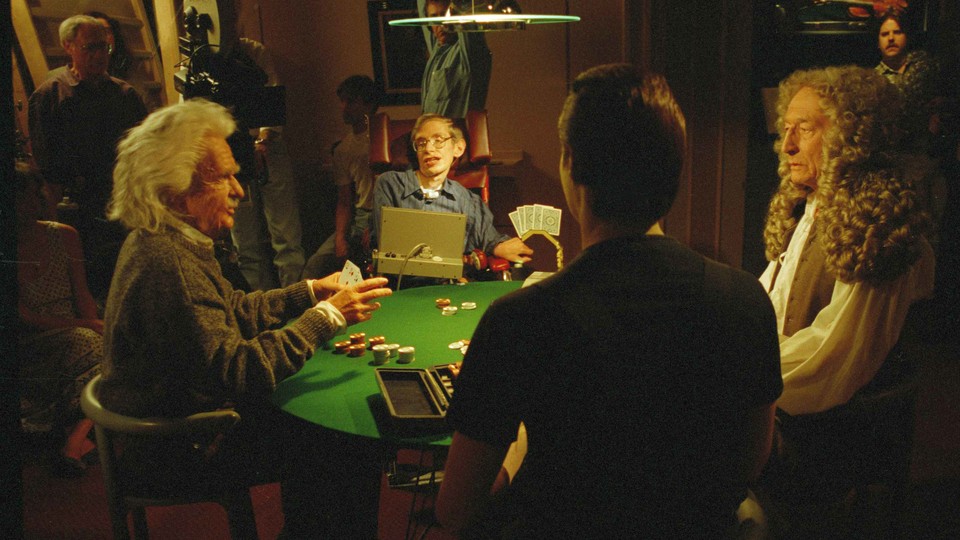

His impish sense of humor was legendary. My friend Alex Singer directed the episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation on which Stephen made a cameo. The scene involved the android Data using the holodeck to summon up a poker game with Stephen, Isaac Newton, and Albert Einstein. According to Alex, Stephen made sure that the script had him defeat Newton and Einstein at poker, thereby showing who was really the smartest guy in the room.

But what I will remember is Stephen’s tireless enjoyment in life. At a cosmology conference in England’s Lake District, the organizers had scheduled a tasting of Scotch whiskeys as an evening’s diversion. As the group of physicists chatted and sampled the wares, I turned around to see Stephen in the back of the room, his nurses helping him taste the various single malts, one by one. His body may have been frail, but his enthusiasm for living was unmatched.