10 LGBT Uprisings Before Stonewall

June 2019 marks the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall riots, when a raid on a New York City gay bar led to riotous protest by people fed up with being harassed, discriminated against and jailed simply for who they were or who they loved.

In the 1960s, New York City stepped up efforts to close gay bars and entrap homosexual men. And establishments catering to queer clientele, none of which were gay-owned, had strong ties to organized crime. Owners would paid off police to avoid trouble, but the bars were still subject to frequent raids. (The New York State Liquor Authority prohibited serving alcohol serving homosexuals, under the guise of barring "indecent conduct.")

The Stonewall Inn had no liquor license—or even running water—but it was the only homophile bar in New York where dancing was allowed. It also drew a diverse clientele—whites, blacks, Latinos, gay men and lesbians, drag queens, trans people, sex workers and young homeless men who often slept in nearby Christopher Park.

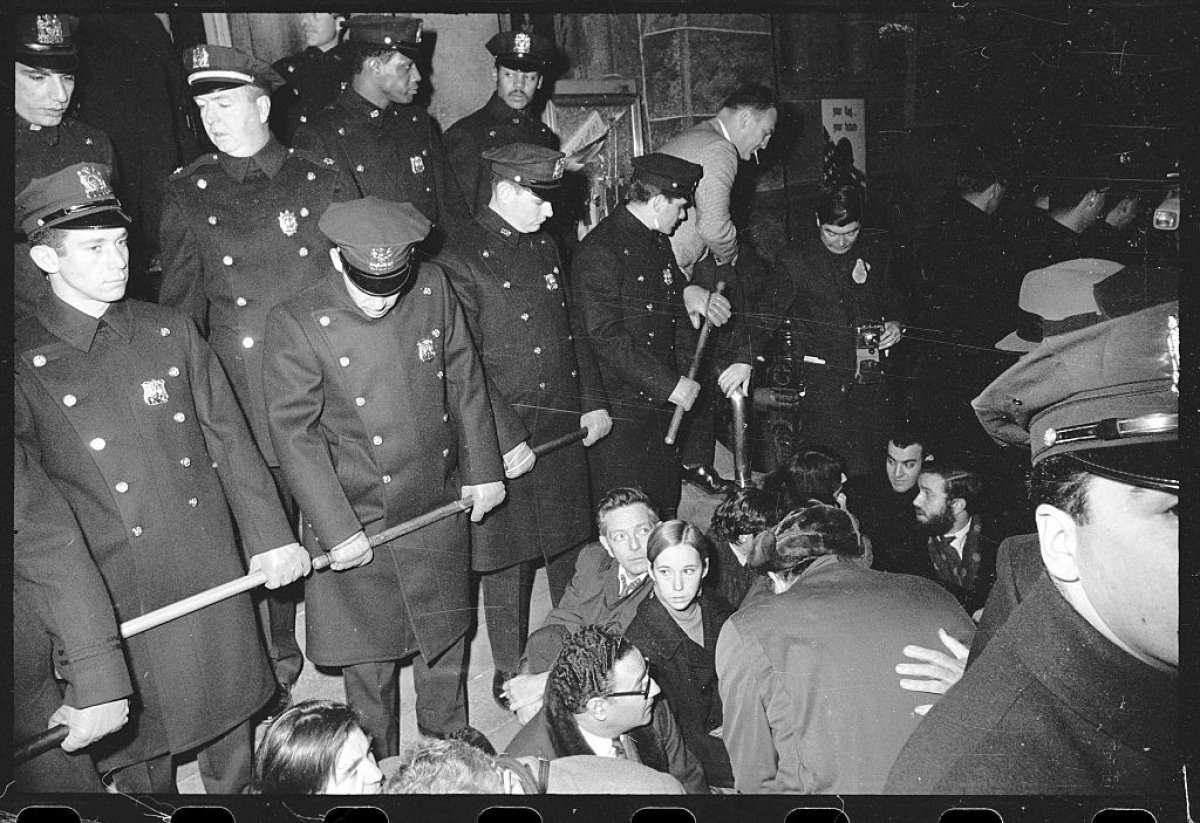

Shortly before 1:30am on June 28, 1969, plainclothes and uniformed officers marched into the Stonewall Inn and announced "Police! We're taking the place!" Unlike previous raids, however, there had been no tip-off. Perhaps because of that, or the growing feeling of resistance sparked by the anti-Vietnam and black power movements, the patrons that night decided they weren't going to go quietly. Some refused to produce identification, others fought back against police who were beating customers. Within minutes, a crowd of more than 100 people gathered outside.

One woman was beaten over the head with a police baton, after reportedly complaining her handcuffs were too tight. When she was picked up and heaved into the back of a police wagon, the crowd exploded. Protestors tried to overturn the wagon. Others hurled bricks, stones and bottles at the building and set garbage cans were set on fire.

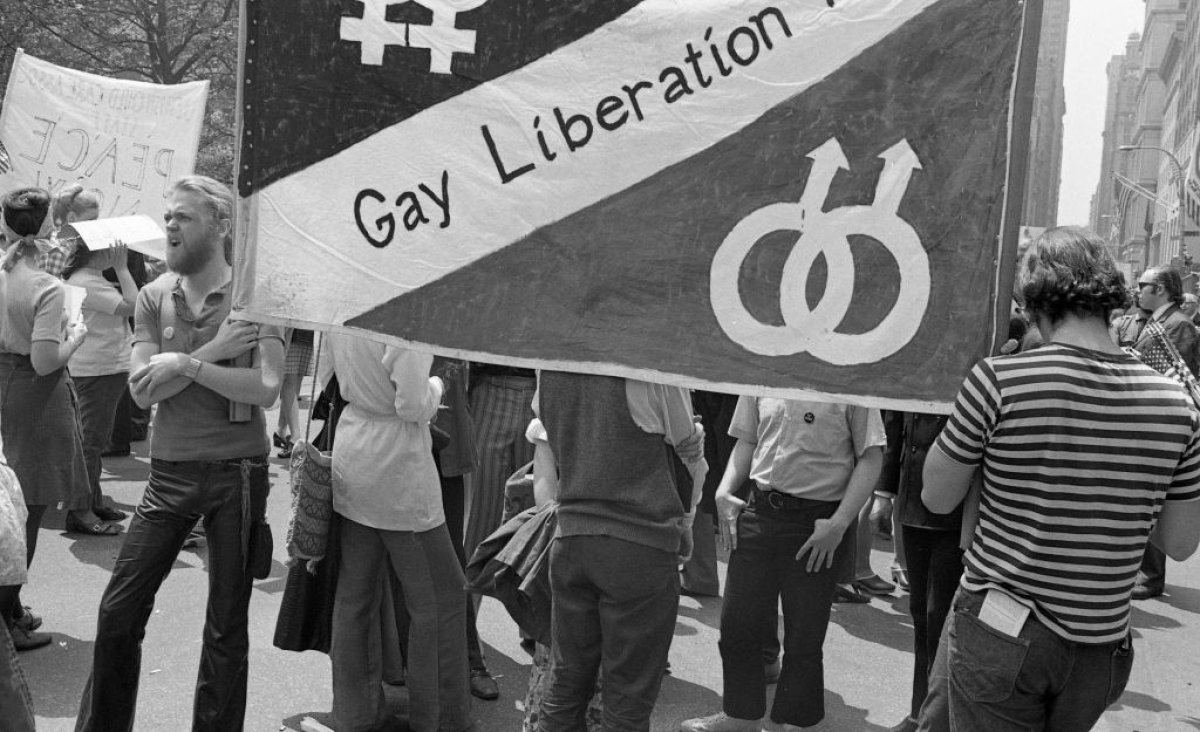

The encounter lasted only a few hours, but protestors returned for the next three nights. Within months, the Gay Activist Alliance and Gay Liberation Front were formed and papers like Come Out! and Gay Power were started, all to keep the momentum of Stonewall alive.

One year later, on June 28, 1970, the first Pride marches were held simultaneously in New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco and Chicago. In 1971, marches were inaugurated in London, Paris, West Berlin, Boston and elsewhere. Today, parades, festivals and other events are held throughout June to commemorate Stonewall and honor the LGBT community.

But what happened that night in the West Village wasn't the first time LGBT Americans stood up for its rights. It was the first encounter to be widely covered by the press, and the first to launch an annual nationwide event, but there had been pickets, demonstrations—and even riots—across America and beyond years before.

In honor of Pride month, we look at 10 of the pre-Stonewall incidents that fueled the fire for dignity, equality and justice.

The Cooper Do-nuts Riot, Los Angeles

May 1959

A full decade before Stonewall, police faced another angry crowd when they tried to round up the gay men, trans women, hustlers and drag queens who frequented a late-night L.A coffee shop.

As had happened before, officers entering Cooper's demanded identification: If a customer's gender presentation didn't match the gender on their ID, they'd be taken to jail. They attempted to arrest several customers—including author John Rechy, who recounted the incident in City of Night—but onlookers threw coffee, donuts and trash and the cops fled empty-handed. As the riot spread into the streets, police backup blocked off Main Street and arrested more protestors. The incident is considered one of the first LGBT uprisings in the U.S.

Picket at Whitehall Street Induction Center, New York

September 19,1964

In what's believe to be the first organized demonstration for gay rights, protestors picketed the U.S. Army Building at 39 Whitehall Street in Downtown New York, which had been an Armed Forces Examination and Entrance Station since 1886.

The group, led by Randy Wicker and members of the Sexual Freedom League, demonstrated against the military's discriminatory policies and the outing of homosexual men rejected for service.

It would be 47 years before the U.S government lifted the ban on gays and lesbians in the military in 2011.

ECHO White House Demonstration, D.C.

April 17, 1965

Less than a dozen demonstrators picketed the White House in the first in a series of actions conducted by the East Coast Homophile Organization (ECHO) in 1965. The following day, though, 29 ECHO members protested outside the United Nations over the treatment of homosexuals in both Cuba and the United States. Other ECHO demonstrations that spring took place in front of the Pentagon and the State Department.

On May 21, Armed Forces Day, 35 people walked a second picket line at the White House, protesting the exclusion of homosexuals from the military, the dishonorable discharges given to those who were discovered and the "continuing refusal by the Departments of Defense, Army, Navy, and Air Force to meet with spokesmen for the homosexual community to engage constructive discussion of the policies and procedures at issue."

Council on Religion and the Homosexual Ball, San Francisco

January 1, 1965

Established in 1964 to foster a dialogue between clergy and gays, the Council on Religion and the Homosexual held a lavish drag ball at San Francisco's California Hall on New Year's Day 1965. The group had worked diligently to follow municipal code and even told the SFPD about the party.

Police were dissuaded from pressuring the hall to cancel the party, but they showed up with kleig lights and cameras to snap photos of attendees, including clergymen and their wives. Officers also repeatedly entered the venue under the guise of "making an inspection." When attorneys retained for such an eventuality challenged police intrusion into a private event, they were arrested. (The ticket taker at the front door was also picked up, as were two male guests.)

The next morning, clergy leaders held a press conference decrying police harassment of homosexuals. Their public action inspired San Francisco's nascent gay rights movement—and the incident at California Hall is often described as San Francisco's Stonewall.

Dewey's Lunch Counter Sit-In, Philadelphia

April 25, 1965

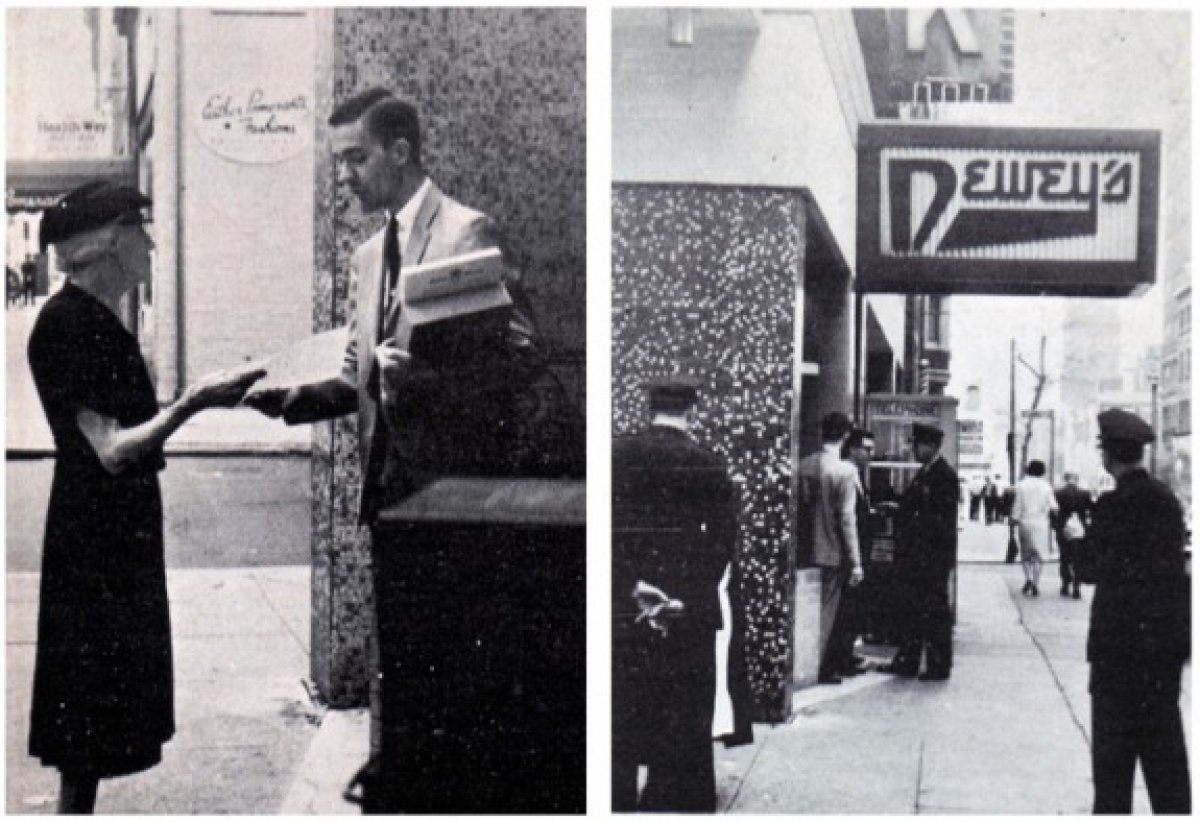

Dewey's was a chain of hamburger joints in Philadelphia, and the location near Rittenhouse Square was a popular gathering spot for young queer people. But after an encounter with rowdy gender-nonconforming teens, employees began refusing service to any customers they believed to be gay or who otherwise challenged gender norms.

On April 25, 1965, 150 people were refused service at the eatery. Working in conjunction with a local gay rights group called the Janus Society, three teenagers walked into Dewey's that day and staged a sit-in. The demonstrators and Janus Society president Clark Polak, who had come down to help, were soon arrested and charged with disorderly conduct.

According to Polak, their protest "was a result of Dewey's refusal to serve a large number of homosexuals and persons wearing non-conformist clothing."

In the wake of the arrests, the Janus Society picketed Dewey's, distributing 1,500 leaflets over the next of five days. A week after the initial demonstration, another smaller sit-in took place. The police arrived but, this time, there were no arrests—and Dewey's stopped denying service to people who appeared homosexual. Polak said authorities told him, "we could stay in there as long as we wanted, as the police had no authority to ask us to leave."

Drum magazine, which was published by Janus, called the action "the first sit-in of its kind in the history of the United States."

The Independence Hall "Annual Reminders," Philadelphia

July 4, 1965

Four years before Stonewall, Frank Kameny, Barbara Gittings and 38 other activists picketed outside Philadelphia's Independence Hall to demand equality, in what was the largest gay rights demonstration of its time.

They carried signs reading "No society can be great without all of its citizens" and "15 million homosexual Americans ask for equality, opportunity, dignity." The men were directed to wear suits and ties, and the women dresses and makeup, to illustrate how clean-cut and mainstream they were.

Held every Independence Day for the next four years, the demonstrations became known as the Annual Reminders.

The Julius' Sip-In, New York City

April 21, 1966

In the 1960s the New York State Liquor Authority barred establishments from serving alcohol to homosexuals. To demonstrate against this discriminatory policy, members of the Mattachine Society took a page from the civil rights movement: They walked into Julius' in New York's West Village, announced they were homosexuals and asked to be served.

The bar had been raided a few days earlier, and a uniformed cop was stationed outside the door. "So we knew that Julius' would not serve us because they have this thing pending," former Mattachine Society chair Dick Leitsch told NPR. "When we walked in, the bartender put glasses in front of us, and we told him that we were gay and we intended to remain orderly. We just wanted service. And he said, 'Hey, you're gay, I can't serve you,' and he put his hands over the top of the glass."

The men had tipped off the media and the Sip-In was covered in the Village Voice and The New York Times, which ran the headline "3 Deviates Invite Exclusion by Bars."

With the help of the ACLU, the Mattachine Society filed discrimination charges with New York City's Commission on Human Rights. "The whole thing ended up in court," said Leitsch, "and the court decided well, yes, the Constitution says that people have the right to peacefully assemble and the state can't take that right away from you. And so the Liquor Authority can't prevent gay people from congregating in bars."

Leitsch says the Sip-In marked the first time the LGBT community really fought back and won in court. "We just sort of [took] in everything passively, didn't do anything about it. And this time we did it—and we won."

Compton's Cafeteria Riot, San Francisco

August, 1966

In the 1960s Gene Compton's cafeteria in San Francisco's seedy Tenderloin neighborhood was one of the few places that hustlers, street kids and transgender sex workers could go late at night. But staffers frequently called the police, who would harass customers and arrest the women for "impersonating a female."

When an officer manhandled a trans woman during an raid in 1966, she threw coffee in his face and the scene erupted into chaos, as a crowd of 60 began throwing dishes and furniture at the police. Rioters smashed the restaurant's windows, chased police into the street and destroyed a patrol car. A nearby newsstand was set on fire.

In the end, dozens of people were thrown into paddy wagons.

The next night, a picket was held outside Compton's, which refused to allow transgender customers back in. One of the first protests against police violence aimed at transgender people, it ended with the restaurant's re-installed plate-glass windows being smashed again.

Still, the city met with protestors and, in 1968, the National Transsexual Counseling Unit [NTCU] was established. It was overseen by SFPD Sergeant Elliott Blackstone, the first police officer in America to serve as a liaison to the "homophile" community.

Black Cat Protests, Los Angeles

February 11, 1967

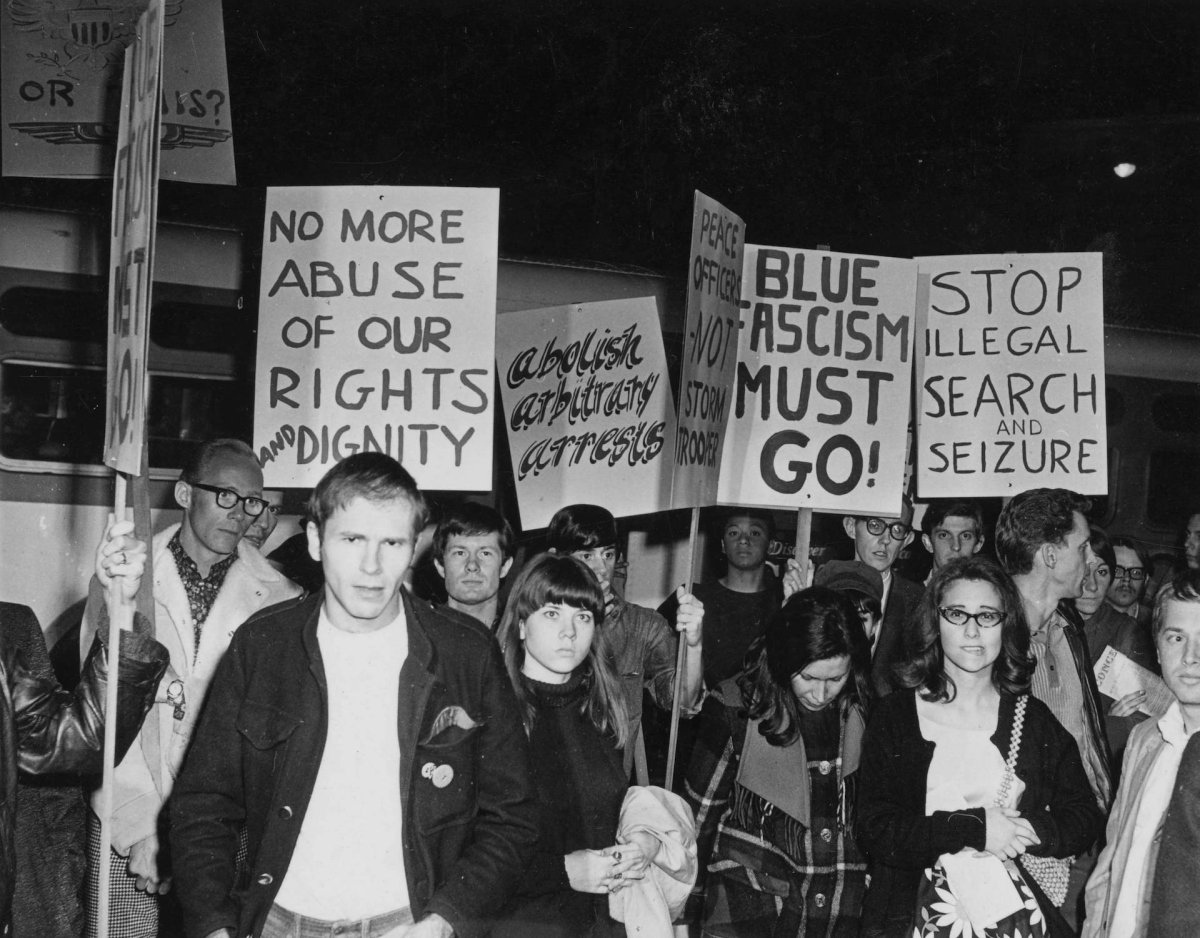

On New Year's Day 1967, undercover cops raided the Black Cat Tavern in Silver Lake, brandishing guns and beating patrons with clubs and pool cues. A bartender was pulled across the bar, lacerating his face on broken glass. Several drag queens were arrested, as were two men engaging in a New Year's kiss. (The couple was convicted of lewd conduct and had to register as sex offenders.)

Weeks later, 200 protesters picketed for days in front of the tavern, marking the first time LGBT people organized against police harassment. They were met by squadrons of armed officers, but continued their peaceful protest.

The Black Cat raid and subsequent demonstrations inspired Richard Mitch and Bill Rau to turn a local gay rights newsletter into The Los Angeles Advocate, which soon became The Advocate, the nation's first national LGBT newsmagazine.

In 2008, The Black Cat was designated as the first Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument landmarked for its significant role in LGBT history. On February 11, 2017, activists re-enacted the picket outside Black Cat to commemorate the demonstration's 50th anniversary.

Today, the Black Cat is a gastropub serving a diverse clientele. Photos from the protests hang on the walls inside.

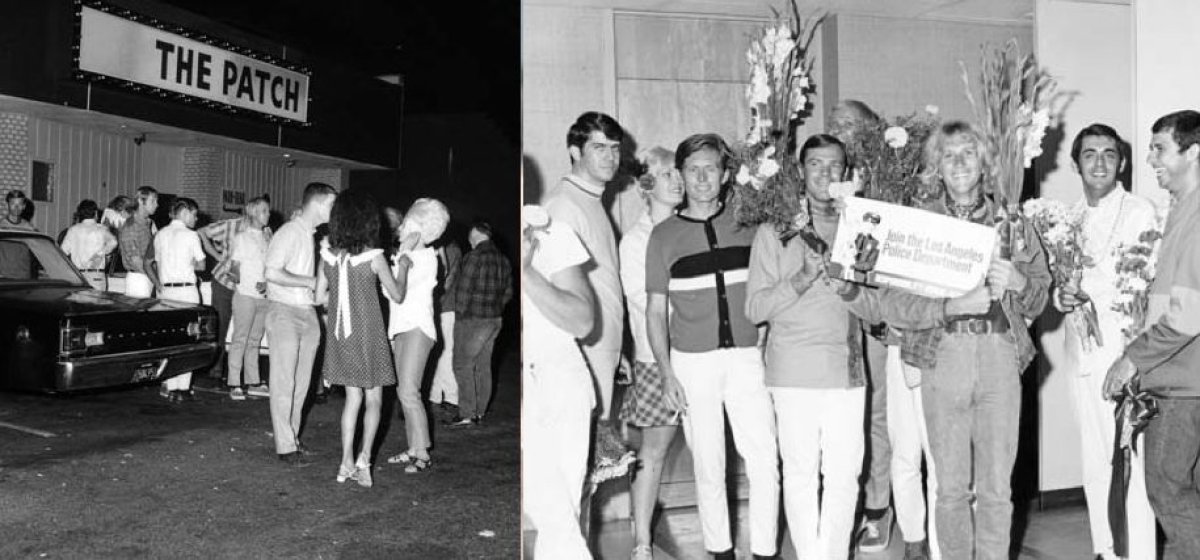

Patch Riot, Los Angeles

August 17, 1968

In 1964, Life magazine reported that the LAPD was on a "anti-homosexual drive" to stop gays from creating what it described as a "fruit world." LAPD inspector James Fisk warned, "The pervert is no longer as secretive as he was—he's aggressive and his aggressiveness is getting worse."

Police repeatedly told Lee Glaze, owner of Long Beach's the Patch, that to stay open he had to ban drag acts, physical contact and male-male dancing. But after business took a hit, Glaze instituted a new protocol: He'd just warn customers when undercover officers were in the bar by playing "God Save the Queen" on the jukebox.

On August 17, 1968, the vice squad arrived, demanding IDs and making arbitrary arrests. Glaze jumped on stage and yelled, "It's not against the law to be homosexual and it's not a crime to be in a gay bar!" He then led customers in protest chants and told them he'd cover their legal costs if they got arrested.

Two men were detained for "lewd conduct" but, unlike other clashes between gay bargoers and police, the Patch remained open that night. The band resumed playing and some 250 people kept on dancing.

"For the first time in memory, a gay bar not only survived the aftermath of a police raid after so many failed before, but thrived, thanks to the bar manager's taking on the police on their home turf," Box Car Bulletin wrote in 2016. "And there was another important first: instead of fleeing, never to return, customers stood by the Patch after the raid."

Glaze found out where his customers were being held and led a crowd of about 25 to the station, giving each a flower from the florist shop he bought out along on the way. The "Flower Power" rally took over the Harbor Division Police Station's waiting room at 3am, prompting desk officers to call in reinforcements. "One flower hits me, and you're going to be charged with assault on a police officer," warned the sergeant on duty. Soon a bondsman arrived and posted bail, but the police held the two men for several more hours before ultimately dropping the charges and releasing them at dawn.

"If all gay bars had customers such as mine, there would be no further harassment from various agencies such as the ABC, the police, and the so-called 'straight' public," Glaze wrote to the Advocate in October 1968. "Throughout these problems their attitude has been 'We' re doing nothing wrong. We're hurting no one. There is nothing illegal about being in a gay bar. There is nothing Illegal about a bar being gay. And we're staying. Period."

Rev. Troy Perry was present at the Patch raid—and in fact his boyfriend, Tony Valdez, was one of those arrested. After spending the night in jail, Velez told Perry "God doesn't care about us." In the face of such disillusionment, Perry decided to form the Metropolitan Community Church, which today includes more than 220 congregations around the world.