Update 17th August, 17:40. This post has been revised since we originally published it. Initially, we thought the process we describe here worked against larger centres but we have realised this is not the case. However, we have noticed some other minor issues with the process that we describe below for posterity.

Last week, Ofqual released details of its A-Level and GCSE standardisation model in a technical manual and accompanying data processing specification.

We’ve spent a bit of time trying to get our heads around it. As we’ve read it in detail, and read other commentary, particularly two highly recommended posts (this from George Constantinides and this from Tom Haines), we’ve learned more.

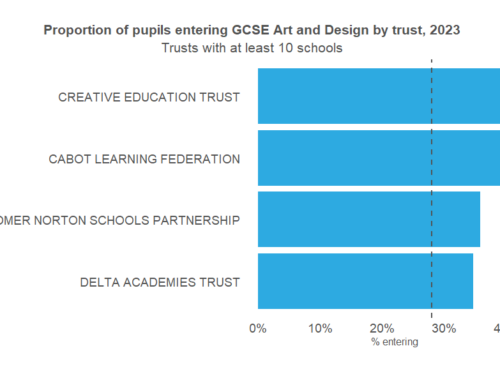

Last week, in this post, we came to the conclusion that in subjects with typically small entries, such as modern foreign languages and music, results increased by a greater amount than in other subjects due to the greater proportion of centre assessment grades (CAGs) included in the total.

But while we still think this is true, we think it could also occur because of the approach Ofqual has taken to achieve the desired national distribution of grades in each subject.

We should say that our thoughts about all of this are evolving all the time as a result of setting out what we think is happening and then responding to constructive challenge. Consequently, we will keep this under review and make changes either to improve explanation or to correct errors.

The calculation of notional marks

To begin with, a notional grade distribution is determined for each subject at each centre based on historic results, adjusted for prior attainment. These grades are then awarded to students in order of the ranks supplied by centres.

In “small” centres or those without historical data, the CAG is used in place of the notional grade. This is how CAGs, which are likely to be more leniently graded, enter the moderation process.

For each subject, there is a “desired” national distribution that Ofqual tries to achieve, based on historic performance adjusted for prior attainment. If the notional grades match this target distribution, those grades are awarded.

But in cases where the notional grades and the target distribution don’t match, students are moved up and down accordingly. There does not seem to be any information on how often this occurs in what Ofqual has published, though do point it out to us if you see it.

To make this adjustment, students are assigned a notional (imputed) mark based on their notional grade and the rankings provided by teachers. While the exact numbers don’t matter, Ofqual has used an initial mark scale of size 100 for each grade: grade U is between 0 and 100, E between 100 and 200 and so on.[1] The calculation of marks places students at each centre evenly within this mark range.

While there is an equation for this provided in Section X8 of the data specification, it might be more easily understood using some examples.

Worked examples

If a centre has two students with a notional grade of C, these students will be given marks between 300 and 400. Students are then awarded marks based on their rank position within the set of students with the same notional grade, but calculated using the expected (fractional) number of students [2], with that grade, based on an earlier step of Ofqual’s calculation.

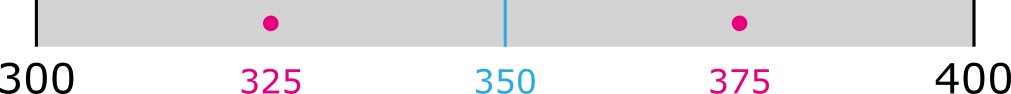

If the expected number is exactly 2.0, the range would be divided into two so that one student is between 300 and 350 with the other between 350 and 400. The students are given marks at the midpoint of these ranges: that is, they are given marks of 325 and 375, with the one ranked higher by the teacher getting 375.

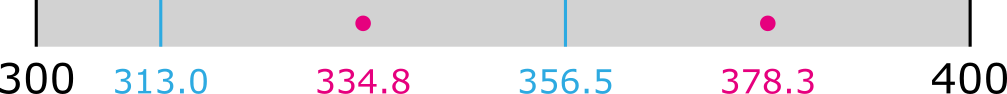

If instead, the expected number is 2.3, the range is split into portions of 43.5 (100/2.3) each (starting at the range maximum) with students awarded grades at each midpoint that falls within the range. The students would then be given marks of 334.8 and 378.3.

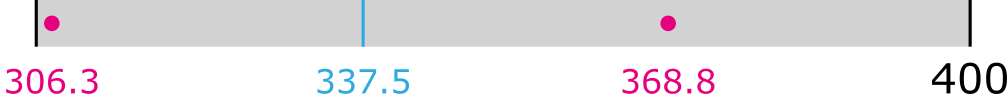

Similarly, if the expected number is 1.6, the range is split into portions of 62.5 and students given marks at the midpoints lying inside the range: 306.3 and 368.8.

Once these marks are assigned, the grade boundaries are adjusted up or down, in a manner similar to the adjustments made to exam grade boundaries by each exam board in a typical year, so that the number of students with each grade is closer to the ‘desired’ (national) distribution.

It is clear from the examples above that the distribution of marks given can place the lowest ranked student within a grade very close to the range minimum, where they will be likely to get shifted down, even where the centre’s distribution is such that students tend to achieve higher grades. However, we should say we do not have any idea how often this actually happens.

This could even happen in centres where a single pupil had a notional grade of C and all other pupils had a notional grade of B. If the expected number of grade Cs at the centre was less than one , then there is a strong chance that the pupil given the notional C would be rounded down to D.

Why A-Level results in music might have increased

There are some other potential issues with the linear distribution of marks within grades, particularly where the number of students entered for a given subject is small.

For example, consider music, where the number of students studying the subject nationally at A-Level is very small.

Then, where music is taught, there are typically fewer than 10 students in a cohort. As a consequence of these small cohorts, the CAG will generally be used in place of the notional grade.

These students will not usually all have the same notional grade, so the number with a given grade might be typically fewer than 10 and since the CAG is used, it will be an integer. When the numbers are small and discrete like this, the proportion of students with identical marks nationally will be high – for example, every centre with two, six or 10 students with a CAG of C will have a student with a notional mark of 325.[2]

Given that the proportion of students who have the same mark is large, the proportion of students who would be subjected to a grade shift if the grade boundaries were adjusted would also be large – and would potentially result in an over-correction of the grade distribution. This means that Ofqual’s ability to adjust the national distribution towards the ‘desired’ one is limited in these cases, which might contribute to the marked increase in the results for some subjects.

So this inability to split ties may help explain why results in A-Level music have increased.

However, we cannot be certain given the information currently available. Further school-level information on the numbers of grades revised upwards or downwards from the expected distribution for 2020 would be necessary.

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from FFT Education Datalab? Sign up to Datalab’s mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive the team’s half-termly newsletter.

1. Note that these are not marks as such – the ranges contain an infinite number of possible values.

2. The expected number of students is the expected percentage of students for a given grade converted into pupil numbers. So if 10% of students are expected to obtain a C and there are 60 students at the centre then the expected number is 6.

3. With two students, these would be given notional marks of 325 and 375.

With six students, these would be given notional marks of 308.33, 325, 341.67, 358.33, 375 and 391.67.

With 10 students, these would be given notional marks of 305, 315, 325, 335, 345, 355, 365, 375, 385 and 395.

Very interesting…

But wouldn’t OFQUAL would make a larger notional mark adjustment in a small school in order to obtain the desired final grade distribution, so the actual changes of grade profile would be the same?

Secondly the larger centre has a larger cohort of un-adjusted students above the adjusted mark. So, if a slightly larger adjustment were to be made than in your example 50% of the grades would change in the small school, but in the larger school the fraction of students adjusted would be smaller (although a larger absolute number of students).

I didn’t see the previous version of this post, but I’d wondered if this imputed mark calculation would work against large centres (as with more students to space out within each grade, some tend to get pushed lower down the range). Could you explain what you found out to show that it doesn’t? Thanks!