Singlehood

Emma Watson and the Rise of the "Self-Partnered": Analysis

Being self-partnered is a self-commitment to autonomy and self-development

Posted November 7, 2019 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

Emma Watson, who rose to fame as Hermione Granger in the Harry Potter films, has just broken out with a new definition of her status: She prefers to define herself as "self-partnered" rather than single, as she approaches her 30th birthday.

She used the phrase in an interview with British Vogue's Paris Lees, in which she discussed the pressures of turning 30. She said she initially did not understand the "fuss" that surrounded the milestone.

However, she has started feeling "stressed and anxious" about her upcoming birthday recently.

She told British Vogue: "If you have not built a home, if you do not have a husband, if you do not have a baby, and you are turning 30, and you're not in some incredibly secure, stable place in your career, or you're still figuring things out... There's just this incredible amount of anxiety."

Speaking of how she had never believed the "'I'm happy single' spiel," she added: "It took me a long time, but I'm very happy [being single]. I call it being self-partnered."

What Is "Self-Partnered"?

Being "self-partnered" is more than just a curiosity, it is a whole new identity that is rapidly spreading. People are tired of the stigma of the term single, which, studies showed, wrongly equals for many to being alone, desperate, unattractive, and even antisocial.

In fact, the very limited number of definitions of relationship status on Facebook, for example, or in any governmental document, should be changed. They are strongly influenced by the cultural definition and subjective perception of singlehood in a heteronormative world: the unquestioned assumption that people are heterosexual and should conform to ideals of family life. Singlehood, in this sense, is still viewed as a deviant category, or a “deficit identity."

As ideas about what is natural and expected with regard to coupling and marriage shift, people encounter a whole range of possibilities around their identity. Identity is no longer seen as a fixed category, but as an individual process of meaning-making. Choosing singlehood as an identity is thus on the rise now.

The Origins of "Self-Partnered"

But, being self-partnered is more than just a mirrored identity to family-oriented values. In a very dry sense, being self-partnered is a more nuanced version of the already common phrase: sologamy. Sologamy means self-marriage, and is, of course, based on the term monogamy that originated from monos ‘single’ + gamos ‘marriage’.

Sologamy, or self-marriage, represents a fundamental focal change from responsibility to independence and from obedience to self-expression. It is not a semantic modification; this change has rattled societies everywhere.

Starting in the developed world and spreading to developing nations, it demonstrates a transition away from focusing on the social collective (further divided into families as functional units of work and reproduction) toward supporting the aspirations of each individual.

Although still on the fringe, the self-marriage movement is growing. In Kyoto, for example, one can find a two-day, self-wedding package promoted by an agency specializing in travel for singles. The package, reportedly costing around $2,500, includes a gown, bouquet, hairstyling, limousine ride to the ceremony, and a commemorative photo album. These types of services are thriving now in the United States, East Asia, and Europe, and there are plenty of virtual packages and books on this.

Self-marriage has also started to appear in the media. In a 2010 episode of the television show Glee, Sue Sylvester decides to marry herself, following in the footsteps of Carrie, from Sex and The City, who married herself so that she could open a wedding gift registry to replace a lost pair of Manolo Blahnik shoes.

In this context, self-partnered might be a more accurate term because Sologamy is about marriage and, in fact, still refers to the marriage and wedding world and industry. Self-partnered is a fresher term that takes one step further apart from marriage. However, there is still a way to go to be fully at peace with being single at heart, a term promoted by Bella DePaulo.

"Self-Partnered" and Its Set of Values

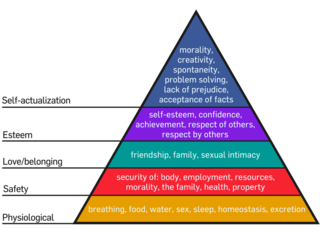

Being "self-partnered" is linked to a set of post-materialist values such as creativity, trying new things, and self-actualization. These values lie at the top of the hierarchy of needs by Maslow. The argument is that when individuals feel secure, they desire to have a unique voice and to materialize their potential and thus turn to their Self (capitalized).

An anonymous blogger, 31, writes:

"In order to go out into the world and be the vivacious, active, creative, and ambitious person that I am, I also need this deeply personal sacred time. And I need a lot of it.

"In a relationship, a lot of this time seems to, for me, get negotiated away. It disappears under the expectation that being involved with someone means wanting to spend ALL free time together... It was very difficult, in many of my past relationships, to have this private, quiet, reflective time."

Such a shift influences the way we think about every social and interpersonal function in our lives. In particular, changes in the importance of the family – once the bedrock of the larger social structure – played a major part in this shift. Aspirations other than marrying and reproducing are taking center-stage now.

Why "Self-Partnered" Is a Pro-Women Term

Emma Watson is also known for her pro-women advocacy, and she does it again in advocating the term "self-partnered."

The negative stereotypes of singlehood are more often applied to women than to men. Single women are either depicted as leading empty, meaningless lives and being morally lacking, or as occupying a confrontational position against the patriarchy. Single men generally escape such stereotyping: unmarried men are assumed to choose their single status.

The fact that singlehood is often understood as a passing or preparatory phase is an indication of the stronghold of heteronormative culture on the definition of singlehood. Rather than being viewed as participating in the “normal” life trajectory, single women are viewed as being downwardly mobile, especially in light of the derogatory term of the 'ticking womb.'

Not only are single men and women perceived in different ways, but heteronormative ideas about marriage, family life, and valid trajectories have an influence on the subjective experience of singlehood and identity. Accordingly, women are more likely than men to describe their singlehood in negative terms. These gender biases are also noticeable in the ways singlehood has been studied: Single women are studied more than single men.

No doubt, singlehood is increasingly viewed as a viable and non-disruptive option. In these narratives of choice, singlehood is commonly described in terms of autonomy, self-development, and achievement rather than in terms of deficit or lack. "Self-partnered" is, therefore, a well-justified term on the scale of relationship statuses and Watson is right in promoting it.

References

Adamczyk, K., & Segrin, C. (2015). Perceived social support and mental health among single vs. partnered Polish young adults. Current Psychology, 34(1), 82-96.

Bernard-Allan, V. Y. (2016). It is not good to be alone; singleness and the Black Seventh-day Adventist Woman. UCL (University College London).

DePaulo, B. (2011). Who Is Your Family If You Are Single with No Kids?

DePaulo, B. (2014). Single in a society preoccupied with couples. Handbook of solitude: Psychological perspectives on social isolation, social withdrawal, and being alone, 302-316.

DePaulo, B. M. (2007). Singled out: How singles are stereotyped, stigmatized, and ignored, and still live happily ever after: Macmillan.

Kislev, E. (2018). Happiness, Post-materialist Values, and the Unmarried. Journal of happiness Studies, 19(8), 2243-2265.

Kislev, E. (2019). Happy Singlehood: The Rising Acceptance and Celebration of Solo Living. Oakland, California: University of California Press.

Kislev, E. (Forthcoming). Social Capital, Happiness, and the Unmarried: a Multilevel Analysis of 32 European Countries. Applied Research in Quality of Life.

Lahad, L. (2017). A Table for One : A Critical Reading of Singlehood, Gender and Time. PB - Manchester University Press.

Moore, J. A., & Radtke, H. L. (2015). Starting “real” life: Women negotiating a successful midlife single identity. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 39(3), 305-319.

Morris, W. L., DePaulo, B. M., Hertel, J., & Taylor, L. C. (2008). Singlism—Another problem that has no name: Prejudice, stereotypes and discrimination against singles.

Reynolds, J., Wetherell, M., & Taylor, S. (2007). Choice and chance: Negotiating agency in narratives of singleness. The Sociological Review, 55(2), 331-351.

Sandfield, A., & Percy, C. (2003). Accounting for single status: Heterosexism and ageism in heterosexual women's talk about marriage. Feminism & Psychology, 13(4), 475-488.

Suen, Y. T. (2015). What's Gay About Being Single? A Qualitative Study of the Lived Experiences of Older Single Gay Men. Sociological Research Online, 20(3), 1-14.