ESPN's Plan to Dominate the Post-TV World

Viewers are shifting their attention from television to smaller screens. Can the most valuable name in media keep up?

On July 11, 2014, LeBron James announced that he was leaving the Miami Heat to return to his hometown Cleveland Cavaliers. Within a few minutes of the announcement, an ESPN notification typed on a desktop computer in Bristol, Connecticut, was sent to more than 6.5 million people in the United States who had signed up for at least one of the company’s news alerts. The message about James’s decision, emblazoned with an ESPN logo, appeared on the lockscreens of more smartphones in the U.S. than the weekly circulation of The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, and USA Today, combined.

“For the next two or three hours after that story broke, there were more people on our website [and app] than were watching SportsCenter,” said Patrick Stiegman, the vice president and editorial director of ESPN Digital & Print Media. The exact figure, ESPN later told me, was 3.7 million people across its digital properties. This was more than a freak data point. It was a signal of mobile’s emergence, proof of the power of the smartphone, and a lesson in the new ways that consumers expect to follow sports—that is, not merely to find news, but also to have the news find them, as well.

ESPN is arguably the most valuable media brand in the world, largely due to its dominant position in the TV sports business. This spring I visited ESPN executives, both at its New York City offices and at its headquarters in Bristol, Connecticut, to learn about how the company is thinking about its audience as it flutters off to Facebook, Twitter, Snapchat, and a distributed media environment where several major companies are searching for a way to build an audience and make money, as television yields to smaller screens and personalized news. ESPN could follow the example of other legacy media companies and selfishly hoard their best content—video, audio, and text—while praying that younger audiences learn to watch and pay for ESPN just like their parents did. Instead, ESPN seems impressively open to learning how the digital generation clicks on and watches ESPN—even if it means changing their own internal definition about what counts as sports news.

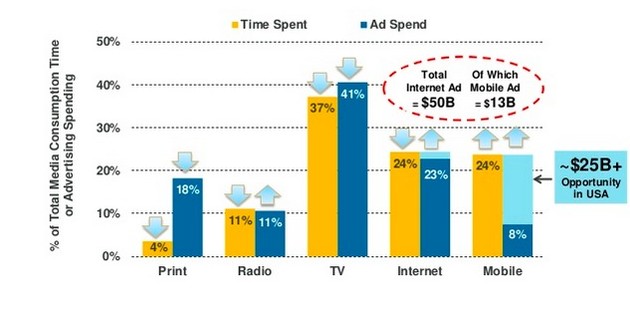

Every year, Mary Meeker, a Kleiner Perkins analyst, delivers an “Internet Trends” presentation that summarizes the state of media and technology in dozens of slides. In 2011, television held a commanding 47 percent of Americans’ media consumption; mobile accounted for just 8 percent. But four years later, Meeker’s 2015 report found that TV’s share fell by ten percentage points to 37 percent, while mobile’s share tripled to 24 percent. (Mobile isn’t just eating into television's time—it’s stealing off of everybody’s plate. Radio's share has fallen from 16 to 11 percent; print is down from 8 to 4; and even desktop is down a notch from 25 to 24.)

The shift to mobile is of particular importance to ESPN, which has a lot to win in the new distributed media environment, but also, perhaps, the most to lose. The present is certainly not “post-TV” for ESPN. It is the most popular cable network in America and the only top-10 cable channel whose 18-to-49 primetime audience grew in 2014. It’s easy to be lugubrious about the future of old-fashioned TV, but sports can still attract record viewers. The College Football Championship that aired on ESPN this January was the highest-rated cable program ever.

Although the company also owns one of the nation's most read print and digital sports magazines and a massive radio empire, ESPN gets the vast majority of its revenue from TV, particularly from its “affiliate fees.”* Every time a cable TV viewer pays her monthly bill—an average of about $90—an automatic payment of about $6 goes to ESPN, whether that household watches 100 hours of sports a week or zero. These fees, estimated to account for about half of ESPN’s revenue, add up to about $7 billion per year.

But soon, the most valuable piece of glass for ESPN could be the smartphone screen. In an average week, across all of its apps, ESPN delivers approximately 600 million alerts to tens of millions of phones. These alerts, along with ESPN’s more traditional digital offerings, such as its app and its new daily feature on Snapchat, have created a mobile Internet audience that is far larger than its television audience—but also, without anything like an affiliate-fee model to support it, harder to monetize.

For now, ESPN's website receives more monthly unique visitors than competitors Bleacher Report, SB Nation, and Deadspin combined, according to comScore data. But mobile is, for a variety of reasons, a harder venue to “win" in absolute terms. On television, ESPN’s largesse creates an obvious feedback loop: Its wealth allows it to outbid other channels for exclusive access to the most popular sports; popular sports get the best ratings; high ratings attract lucrative ad and affiliate deals; and these deals add to ESPN’s wealth. But a subtle force moves this virtuous cycle: The scarcity of sports contracts. On television, sports rights are exclusive. On the Internet, nothing is.

To appreciate ESPN’s current challenge—and its plan to dominate the Internet as it’s dominated television—some recent history is useful. Three years ago, I visited ESPN’s New York City headquarters on the Upper East Side to learn how the most valuable TV network thinks about the preferences of its TV audience. In the early 2000s, ESPN executives told me, the company expanded its sports portfolio with diminishing returns. Around SportsCenter, its sterling main dish, the network had stuffed the menu with bass fishing, horse racing, salsa dancing, and scripted dramas, such as Playmakers.

When John Skipper, the current president of ESPN, took over TV content in 2005, he proposed an elegant new shorthand for the company's mission: Live sports for the average middle-age male American. "We’re not looking for niche audiences,” Skipper told me in 2013. Instead, ESPN sought to maximize the odds that whenever an American guy tuned into its flagship channel, he would see either a major sport, or coverage of a major story line on one of ESPN’s rapidly multiplying talk shows.

The success that came from ESPN’s mid-decade adjustments appeared to illustrate three lesson for media watchers—even those who associate sports with traumatic high-school memories more than entertainment:

- The power of the mainstream in a world that was supposedly all about niche. ESPN’s SportsCenter revamp in the mid-2000s purposefully promoted major stories and stars over and over in an attempt to encourage the typical sports fan to tune in at any given time. ESPN’s just-the-hits programming philosophy might seem obvious to producers at news networks like Fox News or MSNBC, where in show after show, the anchors change, but story lines lines stay the same. But this was counterintuitive coming the year after the publication of Chris Anderson’s The Long Tail, which told media tycoons that the age of mass consumption was over and that the future of media was all about niche. ESPN had enough money to buy the rights to any sport and show video for just about any story; it focused on the “fat head” of the tail.

- The power of scarcity in a media age otherwise defined by abundance. When I asked Skipper in a later interview what he would do if he were the president of ABC, he said “Buy exclusive rights to the presidential election.” This both was and wasn’t a joke. Imagine if only MSNBC covered Congress, only CNN covered Syria, and only the BBC covered the Iowa primaries. The idea seems absurd. But in fact, only NBC carries the Olympics, only ABC shows the NBA conference finals, and only ESPN broadcasts Monday Night Football. Much of ESPN’s power resides in its incomparable portfolio of exclusive rights to the most popular sports.

- The power of destination websites. Maybe the most consequential thing I heard in my 2012 interviews with ESPN executives was the observation that, because ESPN had SportsCenter and a fleet of exclusivity contracts, it had become a destination site. “Other networks need to create hits,” one executive told me. "We don’t. We are a destination network. People tune in to ESPN without even knowing what’s on.”

But in the three years since I visited with the company, ESPN and other large media firms have faced an unexpectedly sudden migration of their audiences, and particularly younger consumers, toward smaller screens. Today, all three of the lessons above are in question, if not in doubt. When sports fandom splinters from one-size-fits-all TV programming to atomized updates on 200 million phones, does the long tail win, after all? On the Internet, is anything—any report, image, highlight, or attitude—ever only available in a single place? And are social-media portals (like Facebook) replacing publishers (like ESPN) as the destination platforms of the Internet?

For many people, ESPN is synonymous with live sports and SportsCenter, but it’s possible to spend all day immersed in ESPN without owning a television. Its properties include the Bill Simmons-founded (and, recently, Bill Simmons-departed) site Grantland, which caters to the literate sports and culture fan, and Nate Silver’s site FiveThirtyEight, which appeals to left-brainers seeking statistical analysis of the news. Between these and other departments' columnists, feature writers, podcasters, and documentarians, ESPN is already so much more than highlight reels for jocks.

This had led to the creation of a new team of digital producers and editors, called the “Push" team, to speak the lingua franca of the Internet—short, colloquial, off-beat, and irreverent—across social media platforms, such as Facebook, Twitter, and Snapchat, as well as ESPN’s homepage. Just as ESPN searched itself to respond to its sliding ratings a decade ago, the company is now rethinking not only how people want to find news about sports, but also what kind of content they want to find.

ESPN has built its brand on news. But straight news, it turns out, isn’t exactly what thrives on Facebook. "What is least shareable is the final score, or how many points each team has,” said Nate Ravitz, the director of the new Push team. What’s shared, rather, are the stories that make athletes relatable or exceptional. "It’s stuff that is outside of the day-to-day construct of sports,” he said. “It’s [enormous New England tight end] Rob Gronkowski’s cat. It’s a coach dancing in the locker room. It’s the moments we have conversations about, and we want to tell it the way you would tell your friend at the bar."

Ravitz has played various roles in his eight years at ESPN, as editor, on-air personality, and manager within ESPN’s Insider and fantasy-sports divisions, the latter a traffic firehose that delivers hundreds of millions of page views a month during the football season. In the spring of 2014, Ravitz was approached to lead a new team that would focus on the company’s efforts to grow its social-media audience. “Social had risen to be this very powerful form of content distribution and traffic, and ESPN wasn't tapping into that the way that many other companies were, both in the sports world and not,” he told me at his office in Bristol. "It was a much smaller percentage of our external referral traffic than it was for competing sites."

ESPN’s astonishing homepage haul, with tens of millions of monthly visits, should be the envy of just about any other publication. But in a way that followers of management theorist Clayton Christensen might consider archetypal, its strength as a destination site may have made it less responsive to the growth of competitors who sprung to prominence with the help of social media. ESPN’s homepage occasionally drew traffic that rivaled Nielsen ratings for popular cable shows (especially during the NFL season), but until recently, it hadn’t evolved to catch the wave of traffic from Facebook and Twitter. Meanwhile, smaller sites such as Bleacher Report and USA Today’s For the Win were making better use of short, punchy content, which often received tens of thousands of shares and likes, even though they were sometimes using information and video the authors had found, or seen, on ESPN.

Asked to explain his new editorial philosophy in an early meeting last year, Ravitz had a simple message: He wanted ESPN to run the kind of stories that he himself wanted to read. "I told the room, 'Did you see that video where [college basketball coach] Fred Hoiberg was dancing in the locker room after Iowa State’s win?’ and they said it was awesome. I said, 'Did you see the highlights of Tacko Fall, the high school basketball player who's 7-foot-6?’ and they said it was great. I said, ‘Did you see any of that on ESPN?' They said no." This wasn't a debate about highbrow versus lowbrow, or serious news versus clickbait, Ravitz said. "ESPN serves sports fans, and these were popular sports experiences that you could not get from us. That was a problem."

Perhaps this sort of thinking seems obvious, but for a journalist, it is subtly subversive. At journalism school, students might be taught the Four Ws (What, Where, When, Why) and the six elements of news (Timeliness, Proximity, Prominence, Consequence, Human Interest, and Conflict). They are taught how to find sources, ask questions, and organize reporting into paragraphs. They are taught, in other words, to think like a serious journalist. They are not necessarily taught to think like an ordinary reader—especially an Internet reader, that omnivore of opportunity who grazes on silly lists and photos for hours, but will also sit for serious news and even block the occasional half hour to digest a 10,000-word profile.

Ravitz’ Push team reimagines some of the company’s best content for the sports fan who dwells among short-form content and feeds—on Facebook, on Instagram, or even on ESPN.com. The first part of ESPN’s Push strategy is a constantly updating column of digital news, called ESPN Now, which runs along the right-hand side of the homepage and has its own section in the ESPN app. The Now column is a stream of short-form content, including breaking news, notable quotes and tweets from athletes and reporters, memorable moments, and infographics from ESPN’s TV shows. It is, essentially, a Twitter feed, by turns silly and news-breaking, cascading down ESPN’s homepage. On some days, the Now feed flows leisurely and doesn’t add much to the experience of the ESPN homepage. But when during a major event—for example, during a draft, or when several high-profile games are happening at once—it is a relentless, even indispensable, waterfall of updates and reactions that allows the homepage to update at the speed of news.

The second team that Ravitz oversees is notifications, or alerts—brief messages transmitted from Bristol to the lockscreens of tens of millions of phones around the country. Considering how often people look at their phones—and how difficult it can be to get people to pay attention to anything else—the lockscreen is arguably the most valuable real estate in the media world, as the Wall Street Journal tech columnist Christopher Mims has written.

When news breaks in the sports world, or when something notable happens in a game airing on one of its networks, ESPN can send an alert connected to a video highlight or brief story to millions of people. Fans can sign up to receive alerts about individual teams or broader categories, such as Breaking News. More than 500,000 people subscribe to 18 of ESPN’s alerts, including NFL News and MLB News, and each Breaking News alert vibrates in more than than 5 million pockets and purses. The most popular single team is the Dallas Cowboys, with more than 700,000 subscribers—not a bad Nielsen rating, even if it lacks the advertising.

To be a click away from a person’s pocket gives ESPN massive reach, but alerts are invasive, calling for a higher burden of relevancy. If I see 10 articles in the Sunday New York Times that I don’t want to read, I don’t cancel my subscription. But if The Times sends me one strange notification, my annoyance will be immediate and fierce. ESPN alert managers told me that when news is sent to your pocket or purse—"when you literally wear us on your skin,” as one put it—there’s a greater need to get it right. In fact, members of the Push team who specialize in notifications told me that sending fewer and more-relevant alerts has helped them dramatically grow their audience. ESPN doubled its alert recipients in six months early this year. With the single most-opened notification, the guilty verdict for New England Patriots Tight End Aaron Hernandez, more than 100,000 people swiped right.

Finally, there is the social arm of ESPN’s operation, which oversees its prodigious output on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram—the third-party sites that now serve as the news and entertainment homepages for many young people. With 20 million followers on Twitter and 10 Facebook pages with more than 2 million fans, ESPN has an extensive social media following, but Ravitz is mindful that he needs to adopt a particular tone for each social-media audience, which won’t always match those of the network’s other properties. On television, ESPN’s bread and butter is news, analysis, and outspoken opinion. But what travels on Facebook and Twitter isn’t scores, stats, or news, necessarily, but more like what one might call news-like (or, even, news-lite) moments: Tom Brady saying “balls” over and over at a press conference, or footage of Stephen Curry’s young daughter being adorably truculent during a NBA press conference.

On Snapchat, the newest massive social-media platform, where users share photos and videos that disappear after a few seconds, ESPN has developed a daily video production. When you tap the ESPN logo on a Snapchat page, you see a sequence of looping videos that, if you tap or swipe down, reveal a full article or video clip. ESPN's Snapchat app combines the best of the web—where users can control the flow of information with the flick of a finger—and the best of TV—a procession of video that can hold my attention for fidgetless minutes. (Snapchat is so peripheral to my life that I cannot quite make a habit of ESPN’s programming there, but the production is both slick and cheeky; executives declined to share exact numbers for ESPN’s Snapchat reach.)

"Our mindset is we want to experiment and be where the audience is, and something like Snapchat has a huge audience,” Ravitz said, during a tour of the office, where staffers showed me how they upload videos and graphics to the Snapchat app. “We’re still learning how people are swiping up and down, what stories and videos work best. We’re getting that feedback working with Snapchat on a regular basis."

Push represents a distinctive way of thinking about style and distribution, one that other organizations might benefit from. Rather than force a unified ESPN style onto every social-media platform, the team takes care to learn the local language of every territory of the Internet—experimenting with live feeds on its homepage, studying which stories fly furthest on Facebook, and practicing the goofball patois of Snapchat.

ESPN’s internal motto—"to serve sports fans anytime, anywhere”—is repeated so often at the company that, on a walk through its Bristol campus, the phrase passes through stages, from meaning to cliche, and then, perhaps, back to meaning. ESPN is impressively agnostic about where to put it best stuff, sharing ad-free video clips on Snapchat; tweeting its long feature pieces days before the magazine slips into mail boxes; and making an infinity of videos, podcasts, articles, and other forms of content free on its website and in other forms. And all this from the network that can charge cable operators and satellite TV companies the highest rate in the industry, thanks to its exclusive offerings. ESPN has never been more expensive to “buy” as a television station, nor more abundantly cheap to consume online.

And what about the bottom line? The most likely path forward is that ESPN will continue to make billions of dollars from a big cable bundle that is in slow decline, while the company experiments with other ways to make money—for example, with smaller bundles, direct-to-consumer video, and massive digital video advertising—before the bounty from traditional national TV fees starts to fall.

But this isn’t merely a business pivot; it’s a philosophical shift in how ESPN views its audience and its content. Linear TV programming is one product for all; the big money is in the biggest sports and in collecting the fees and ad revenue that comes with them. But on smaller screens, on people's phones and laptops, ESPN shines before a less richly monetized mosaic, and both the content and business strategy is still an experiment in the personal feeds and phones of tens of millions of fans. In a way, ESPN is confronting the slow unbundling of television by unbundling itself—treating its own site, plus Facebook, Twitter, Snapchat, and phone alerts, as separate channels, each with their own appropriate programming and tone. (Not to mention: making its network available on smaller cable bundles.)

Several months after my last column about ESPN, I spoke with its president John Skipper about the website Grantland and why ESPN would spend so much money on a project that didn’t have an obvious, immediate route to profitability. People love Grantland, he said, and ESPN needs to keep making things that are special enough for people to love, because when you get to be as big as ESPN, it’s hard to get people to love you.

The massive transition that Mary Meeker and other analysts are tracking from some distance—the slow erosion of TV and the rise of mobile—will challenge the foresight of Nate Ravitz, the Push team, and executives renovating ESPN for the social-media age. The distributed future of content won’t resemble the model that made ESPN the richest network in the world. Although live sports will command large audiences for a long time, the right home for news and analysis probably won’t look like one site for 100 million people. It will probably look more like 100 million feeds for just as many individuals—not news as one-massive-size-fits-all, but rather something that feels close, individualized, and personal enough to love.

* This article has been updated to clarify that ESPN the Magazine is one of the U.S.’s most read sports magazines in terms of combined print and digital readerships. In terms of print circulation alone, it is not the most read.