FYFD

Celebrating the physics of all that flows. Ask a question, submit a post idea or send an email. You can also follow FYFD on Twitter and YouTube. FYFD is written by Nicole Sharp, PhD.

If you're a fan of FYFD and would like to help support the site and its outreach, please consider becoming a patron on Patreon or giving a donation through PayPal with the button below. Your support is much appreciated!

For a long time, people thought baseball aerodynamics were simply a competition between gravity and the Magnus effect caused when a ball is spinning. But the seams of a baseball are so prominent that they, too, have a role to play. (Image credit: top - Pixabay, others - B. Smith; research credit: B. Smith; see also Baseball Aerodynamics)

Today wraps up our Olympic coverage, but if you missed our earlier posts, you can find them all here.

Read the full article

Like footballs and baseballs, the trajectory of a volleyball is strongly influenced by aerodynamics. When spinning, the ball experiences a difference in pressure on either side, which causes it to swerve, per the Magnus effect. But volleyball also has the float serve, which like the knuckleball in baseball, uses no spin. (Image credit: game - Pixabay, volleyballs - U. Tsukuba; research credit: S. Hong et al., T. Asai et al.; via Ars Technica)

Stick around all this week and next for more Olympic-themed fluid physics!

Read the full article

Embers fly through the Kincade wildfire leaving streaks of light that reveal the strong winds helping drive the fire. This unintentional flow visualization mirrors techniques used by researchers to understand how flows are moving. The shutter of the camera remains open for a fixed time, so the length of each streak tells us about the speed of the flow. Longer streaks occur where embers moved faster.

Here we see the longest streaks in the upper left side of the image, which tells us that the wind was moving faster there than it did at lower heights, like near the photographer in the picture. That’s in keeping with what we would expect. In general, winds move faster above the ground than they do near the surface. That speed difference is one of the reasons wildfires are so difficult to contain; a single ember caught by high winds is easily carried to unburnt areas, allowing the fire to spread more quickly than if it had to burn along the ground. (Image credit: J. Edelson/Getty Images; via Wired)

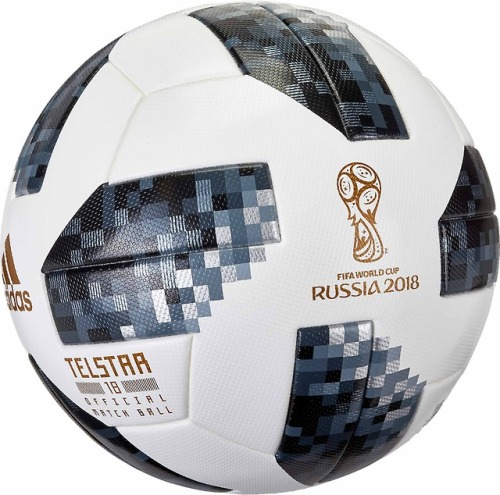

Every four years, Adidas creates a newly designed ball for the World Cup. This year’s version is the Telstar 18, which features six glued panels (no stitching!) with a slightly raised texture. That subtle roughness is an important feature for the ball’s aerodynamics. It helps ensure that flow around the ball will become turbulent at relatively low speeds. Some previous designs, notably the 2010 Jabulani, were so smooth that flow near the ball would not become turbulent until much higher speeds. In fact, one side of the ball might have laminar flow while the other was turbulent, causing the ball to wobble and misbehave. To learn more about World Cup aerodynamics and the importance of a little surface roughness to the ball’s behavior, check out the Physics Girl video below. (Image credit: Adidas; via APS News; video credit: Physics Girl)

One of the great challenges in fluid dynamics is understanding how order gives way to chaos. Initially smooth and laminar flows often become disordered and turbulent. This video explores that transition in a new way using sound. Here’s what’s going on.

The first segment of the video shows a flat surface covered in small particles that can be moved by the flow. Initially, that flow is moving in right to left, then it reverses directions. The main flow continues switching back and forth in direction. This reversal tends to provoke unstable behaviors, like the Tollmien-Schlichting waves called out at 0:53. Typically, these perturbations in the flow start out extremely small and are difficult or even impossible to see by eye. So researchers take photos of the particles you see here and analyze them digitally. In particular, they are looking for subtle patterns in the flow, like a tendency for particles to clump together with a consistent spacing, or wavelength, between them. Normally, researchers would study these patterns using graphs known as spectra, but that’s where this video does something different.

Instead of representing these subtle patterns graphically, the researchers transformed those spectra into sound. They mapped the visual data to four octaves of C-major, which means that you can now hear the turbulence. When the audio track shifts from a pure note to an unsteady warble, you’re hearing the subtle disturbances in the flow, even when they’re too small for your eye to pick out.

The last part of the video takes this technique and applies it to another flow. We again see a flat plate, but now it has a roughness element, like a tiny hockey puck, stuck to it. As the flow starts, we see and hear vortices form behind the roughness. Then a horseshoe-shaped vortex forms upstream of it. Aside from the area right around the roughness, this flow is still laminar. But then turbulence spreads from upstream, its fingers stretching left until it envelops the roughness element and its wake, making the music waver. (Video and image credit: P. Branson et al.)

There are many ways to repel droplets from a surface: water droplets will bounce off superhydrophobic surfaces due to their nanoscale structures; a vibrating liquid pool can keep droplets bouncing thanks to its deformation and a thin air layer trapped under the drop; and heated surfaces can repel droplets with the Leidenfrost effect by vaporizing a layer of liquid beneath the droplet. But all of these methods will only work for certain liquids under specific circumstances.

More recently, researchers have begun looking at a different way to repel droplets: moving the surface. The motion of the plate drags a layer of air with it; how thick that layer of air is depends on the plate’s speed. (Faster plates make thinner air layers.) Above a critical plate speed, a falling droplet will impact without touching the plate directly and will rebound completely. This works for many kinds of liquids – the researchers used silicone oil, water, and ethanol – across many droplet sizes and speeds. The key is that the air dragged by the plate deforms the droplet and creates a lift force. If that lift force is greater than the inertia of the droplet, it bounces. (Image and research credit: A. Gauthier et al., source)

As a child, I loved to ride in the car while it was raining. The raindrops on the window slid around in ways that fascinated and confused me. The idea that the raindrops ran up the window when the car moved made sense if the wind was pushing them, but why didn’t they just fly off instantly? I could not understand why they moved so slowly. I did not know it at the time, but this was my early introduction to boundary layers, the area of flow near a wall. Here, friction is a major force, causing the flow velocity to be zero at the wall and much faster – in this case roughly equal to the car’s speed – just a few millimeters away. This pushes different parts of large droplets unevenly. Notice how the thicker parts of the droplets move faster and more unsteadily than those right on the window. This is because the wind speed felt by the taller parts of the droplet is larger. Gravity and the water’s willingness to stick to the window surface help oppose the push of the wind, but at least with large drops at highway speeds, the wind’s force eventually wins out. (Image credit: A. Davidhazy, source; via Flow Viz)