July 10, 2014

En route to Batumi, Georgia

The first recorded sovereign default was in the 4th century BC when ten Greek cities failed to honor loans from the temple of Delos.

Most of the borrowers could not pay back what they owed and the temple took an 80% loss on its principal.

(Clearly they did not have Janet Yellen or Ben Bernanke to print money and bail out the system…)

As the saying often attributed to Mark Twain goes, “History doesn’t repeat itself but it often rhymes.”

Sometimes history rhymes with surprising frequency.

Argentina has made a long habit of defaulting on their obligations; it’s happened 7 times in the last 200 years.

And now, just 13 years after their last default, there’s serious risk they’ll do so again.

Back in 2001, the Argentine economy all but collapsed. In a matter of days, the country went from mild recession to full-blown economic crisis.

The currency went into freefall. Police were out in the streets shooting protestors. Unemployment and crime rates soared overnight. And the nation defaulted on its debt—a record amount at the time.

Since then, they’ve worked out arrangements to gradually repay most of the bondholders about 30 cents on the dollar, and they’ve already started making interest payments.

But a small minority of bondholders refused that offer. They’re called ‘holdouts’. And they want more.

These holdouts have now been handed a major legal victory from none other than the US Supreme Court (the bonds were written under US law, so technically US courts have jurisdiction).

The decision prohibits Argentina from making any further interest payments to the bondholders they’ve already agreed with until they reach a settlement with the holdouts.

The last payment was due on June 30, so Argentina is already past due.

They have a 30-day grace period to resolve the matter, otherwise the nation will be in default once again.

Candidly, there’s no good way out of this.

Argentina’s economy is in recession again. Foreign reserves are drying up.

And even though the government claims tax revenues are rising, Argentina’s legendary inflation has caused the peso to depreciate by 20% against the dollar so far this year.

So on a US-dollar basis, tax revenues are falling.

There’s no good way out of this for Argentina.

If they reach a deal with the holdouts, it will take a nasty chunk of money out of their reserves.

More importantly, the RUFO clause (Rights Under Further Offers) means that if Argentina DOES reach a settlement with the holdouts, everyone else can line up for the same deal.

That could cost north of $100 BILLION, over 20% of GDP. They simply don’t have the money.

Yet if they don’t reach a deal with the holdouts, they’ll be in default in just three weeks’ time.

Either way, it likely means a fresh round of desperate measures—capital controls, price controls, and credit controls.

Most people in the country are too distracted with the national team’s World Cup performance to notice.

But ignoring the problem doesn’t make it go away. Sooner or later reality bites.

Bear in mind, Argentina was one of the wealthiest countries in the world a century ago– strong and stable with vast natural resources.

These things change. And the warning signs are all there.

The objective data tells us that Argentina is bankrupt… in the same way that the objective data tells us that most of the West is bankrupt.

Most of the West has borrowed far more than they’re credibly able to pay back; the US, France, Spain, etc. all have to borrow money just to pay interest on the money they’ve already borrowed.

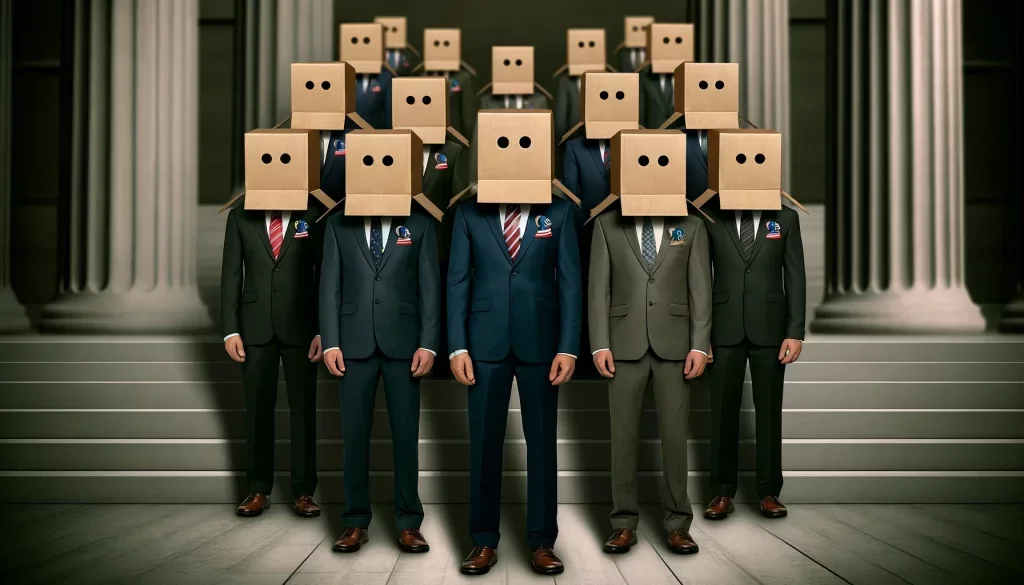

In light of this data, it’s imperative to make sure that you’re not tied to a single system, a single bankrupt nation.

If you live, work, bank, invest, own real estate, operate a business, etc. all in the same country, you are essentially betting your entire livelihood on that one country.

Again, given the data, that’s quite a risk to be taking.

Spreading a portion of your assets and savings across healthy jurisdictions substantially reduces this risk.

If the worst happens—default, capital controls, price controls, bank failures, substantial inflation, etc. then your life won’t be turned upside on the whims of some politician.

Yet even if none of the darkest scenarios come true, you won’t be worse of for having taken these steps.

What’s paramount is to prepare and have options before you need them, and not end up scrambling when disaster strikes. At that point, it will be far too late.